Original 'Stonehenge' discovered, echoing a legend of the wizard Merlin

The earliest megalithic circle at Stonehenge was first built in the west of Wales more than 5,000 years ago, before its stones were dug up and dragged over 140 miles (225 kilometers) to its present site in the west of England, new research suggests.

The findings also support a wild legend that the mythical wizard Merlin ordered giants to move Stonehenge from Ireland and rebuild it in its current location.

The researchers discovered the remains of the original stone circle in the Preseli Hills in Wales, near the ancient quarries where geologists have determined that Stonehenge's famous bluestones were cut. The new study, published Thursday (Feb. 11) in the journal Antiquity, suggests that the bluestones that formed the first stage of Stonehenge may have symbolized the ancestors or lineages of the Neolithic people who lived near the quarries, which may have been why they took the stones with them when they left for a far-off region.

Related: In photos: A walk through Stonehenge

The research could explain the mysterious origins of Stonehenge and why its first builders made such efforts to transport the massive stones almost halfway across Britain. "I had a hunch," said Michael Parker Pearson, an archaeologist at University College London who led the team that made the discovery. "Why would anyone say, 'We're going to build a circle with stones from a quarry 140 miles away?'”

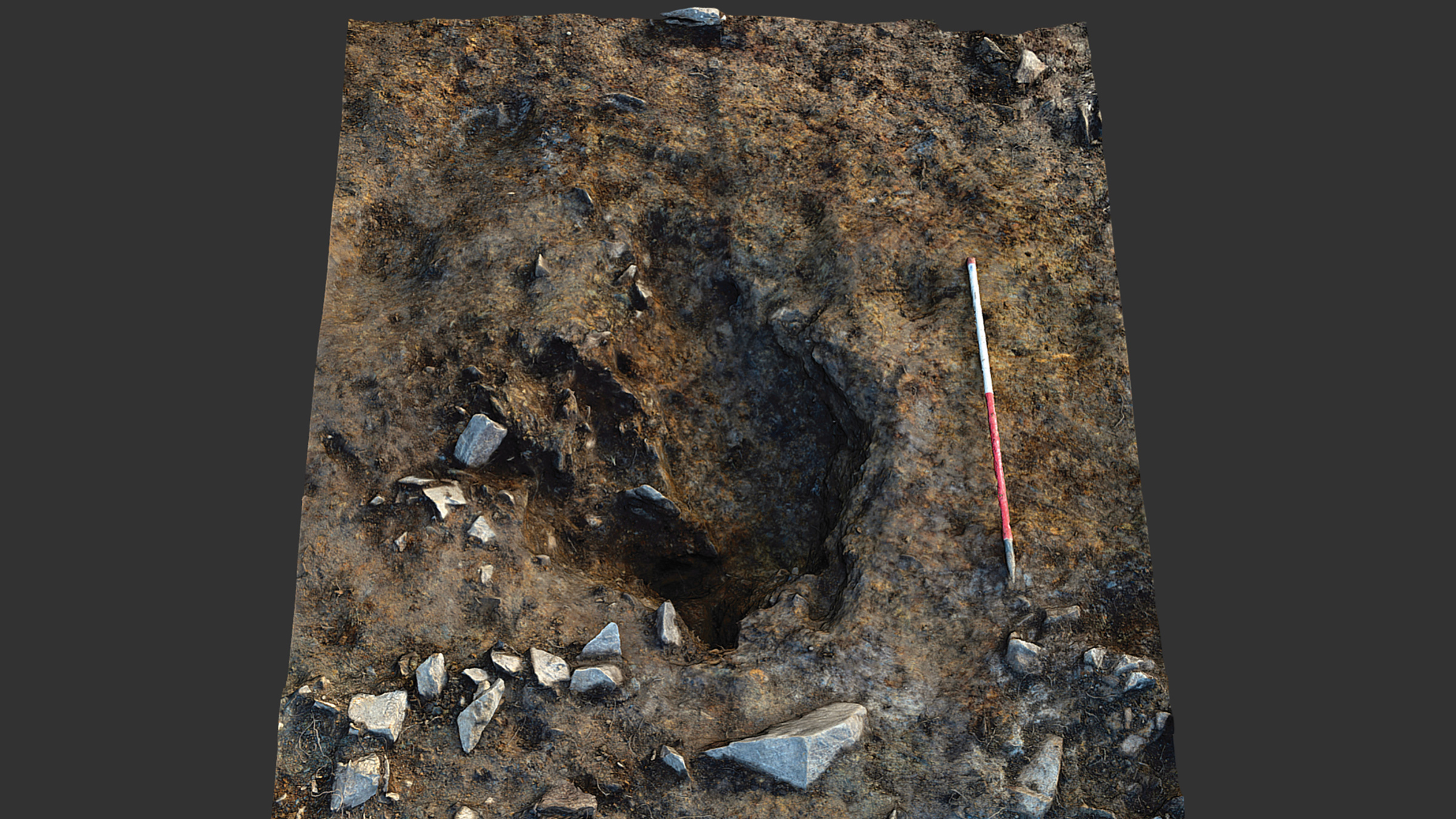

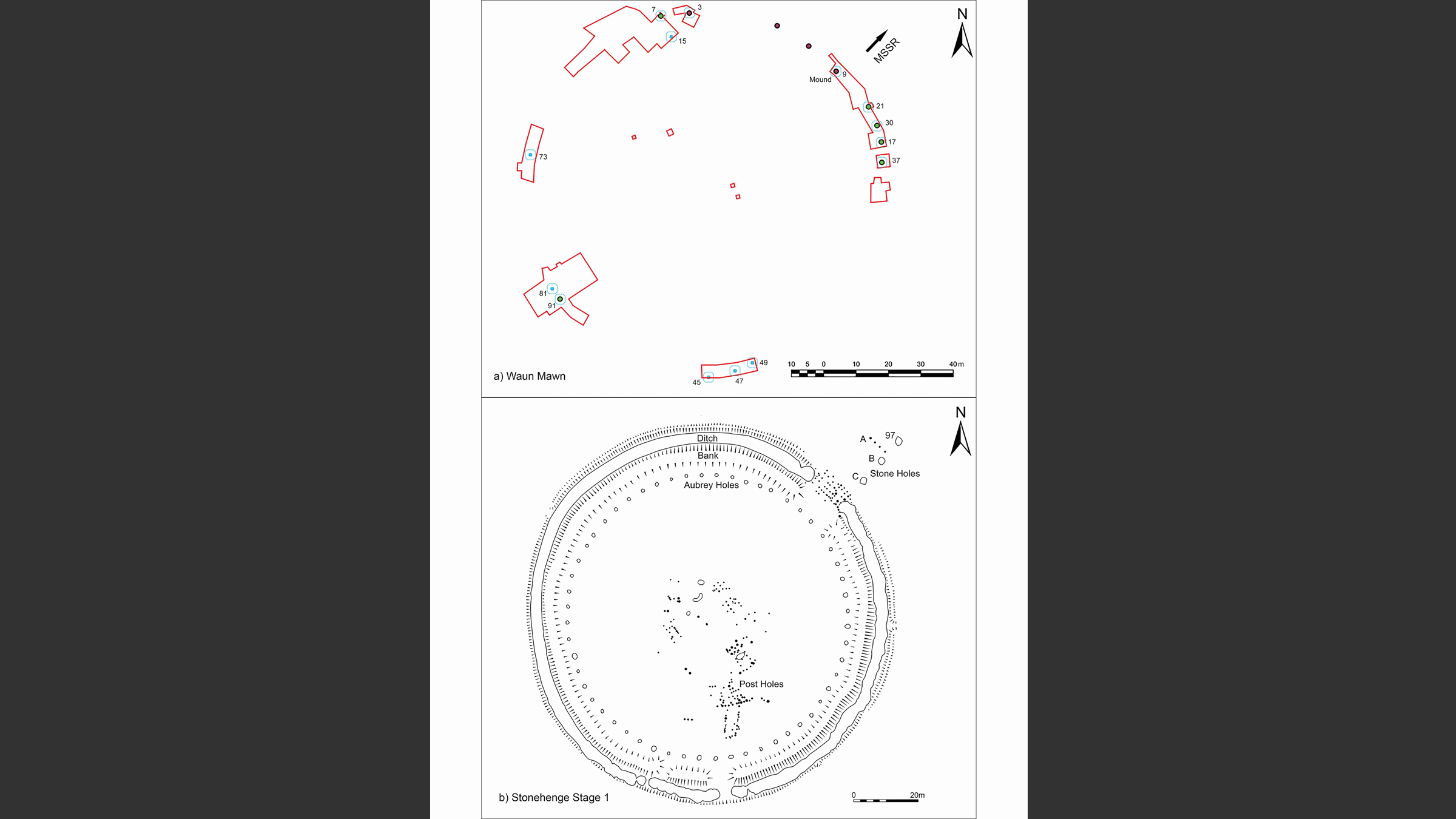

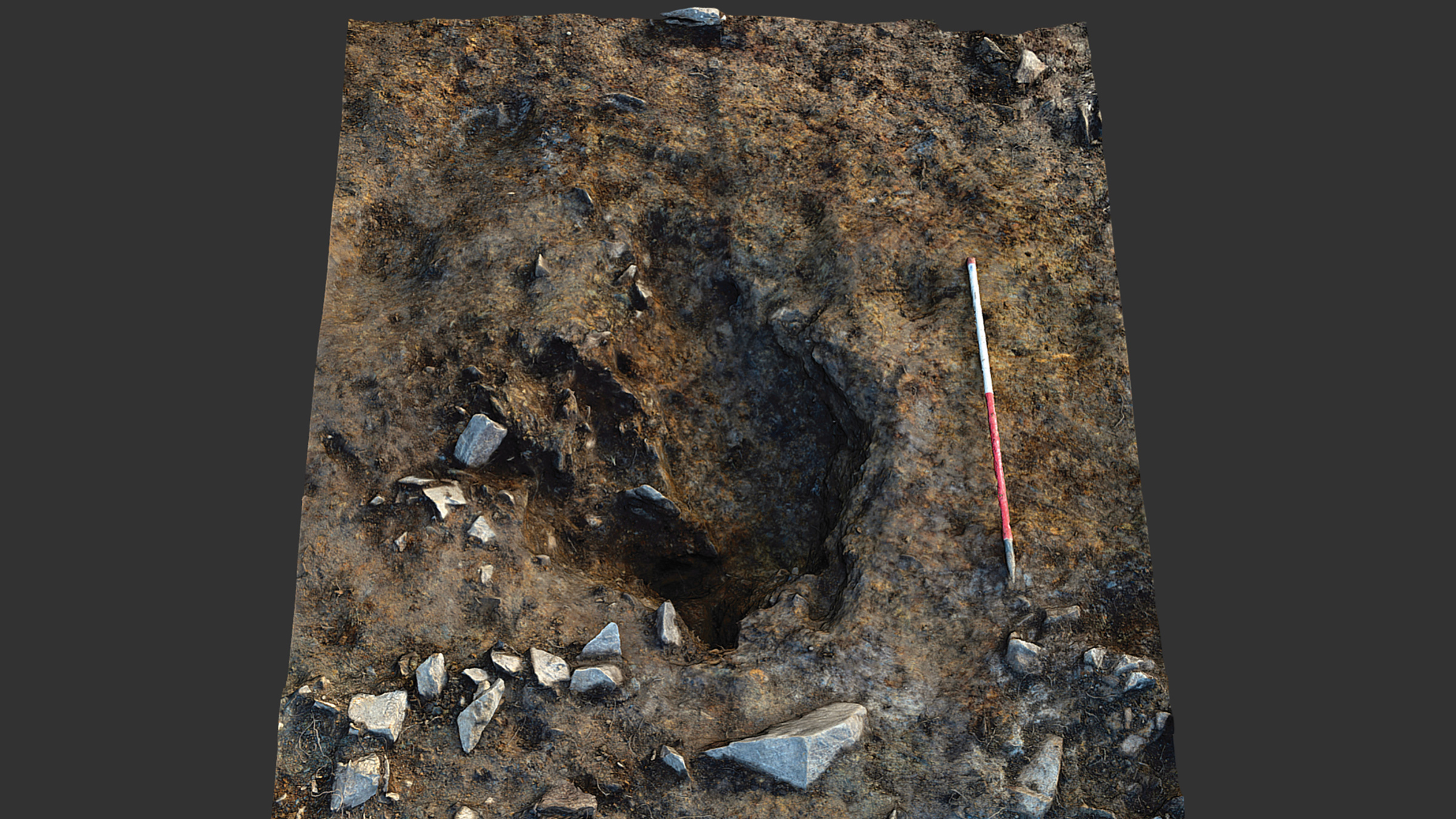

To solve the mystery, Parker Pearson and his team spent more than five years investigating Neolithic stone monuments around the Preseli Hills. In 2017, they determined that four stones at a site called Waun Mawn — "peaty moorland" in Welsh — were all that was left of a much larger circle of up to 60 stones that exactly matched the layout of the original 360-foot-wide (110 m) circle of bluestones at Stonehenge. The rest of the stones at Wuan Mawn had been dug up long ago, Parker Pearson told Live Science.

Ancient stones

Stonehenge is most famous for the giant "sarsens" in its main circle, but these large stones were erected centuries after the monument was first built. Recent research shows the sarsens are local sandstone boulders that were transported only a few miles to the Neolithic monument about 4,500 years ago.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But geologists and archaeologists have long known that the many bluestones that ring Stonehenge, some of which weigh up to 5 tons (4.5 metric tons), were transported in ancient times from quarries in the Preseli Hills. Some of the stones have a bluish tinge when they're newly broken or wet.

Scientific dating of charcoal and sediments from some of the now-empty stone holes suggest Waun Mawn was built about 5,400 years ago, some 400 years before the earliest stage of Stonehenge, the researchers said. One of the stone holes at Waun Mawn also has an unusual five-sided cross section that matches one of the bluestones at Stonehenge and contains chips of the same type of rock.

Parker Pearson said it seems likely that the Waun Mawn stone circle and some other stones nearby were dismantled when entire families left the area to live far away in the east, and that up to 80 of the stones were later erected at the present Stonehenge site.

Related: 7 bizarre ancient cultures that history forgot

Distinctive levels of strontium isotopes in the enamel of human teeth found in ancient graves at Stonehenge shows many of the earliest people buried there did not grow up near its present location in Wessex. Archaeological evidence suggests they had migrated from further west, possibly modern Wales, and so the original stone circle probably marked the site of a new Neolithic graveyard, he said.

Each of the bluestones may have symbolized a notable ancestor or ancestral lineage to the local people, which is why they erected the stones at the new graveyard, he said.

Merlin legend

The researchers aren't sure why so many Neolithic families left the Preseli Hills suddenly to live so far away. Parker Pearson thinks their community may have wanted to unite for political or social reasons with a distant group of people, and so they brought their ancestral stones with them to cement their presence in their new territory.

Calculations of the labor involved in transporting the bluestones, probably by sled, suggest the journey from Waun Mawn to the present Stonehenge site could have been completed in one summer.

"You can cover 3 miles [5 km] a day, if you've got your trackway prepared," he said. "They might have had feasting, food and drink … just like a rolling party that moved from one place to another."

Like Stonehenge, the circle at Waun Mawn was aligned so its some of its stones lined up with the sunrise on the summer solstice; similar alignments have been found at other Neolithic monuments throughout the British Isles, and they could reflect the eternal pattern of movement of the sun in the heavens, he said.

The idea that Stonehenge was first built from a circle of stones transported from a great distance sounds strikingly similar to a medieval legend that Stonehenge was built at the command of Merlin, the legendary wizard who aided the equally legendary King Arthur.

According to the legend, the stone circle was originally located in Africa, and giants relocated it to Ireland to serve as a magical center for healing. Later, the legend goes, Merlin had giants transport the stones to the current site at Salisbury Plain and reassemble them there as a monument to Britons killed while fighting the invading Saxons.

Parker Pearson said that when the legend was written down in the 12th century, the far west of Wales was considered part of Ireland; but it was unlikely the legend described a 5000 year-old folk memory of the Stonehenge relocation — the oldest-known oral histories, the Sanskrit Vedas from India, are estimated to be just 3000 years old. But "I have to admit that the evidence is highly intriguing," he said. "Maybe — just maybe — there's a tiny grain of truth in it."

Originally published on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.