'Love hormone' oxytocin may help mend broken hearts (literally), lab study suggests

The study was done in fish and human cells.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

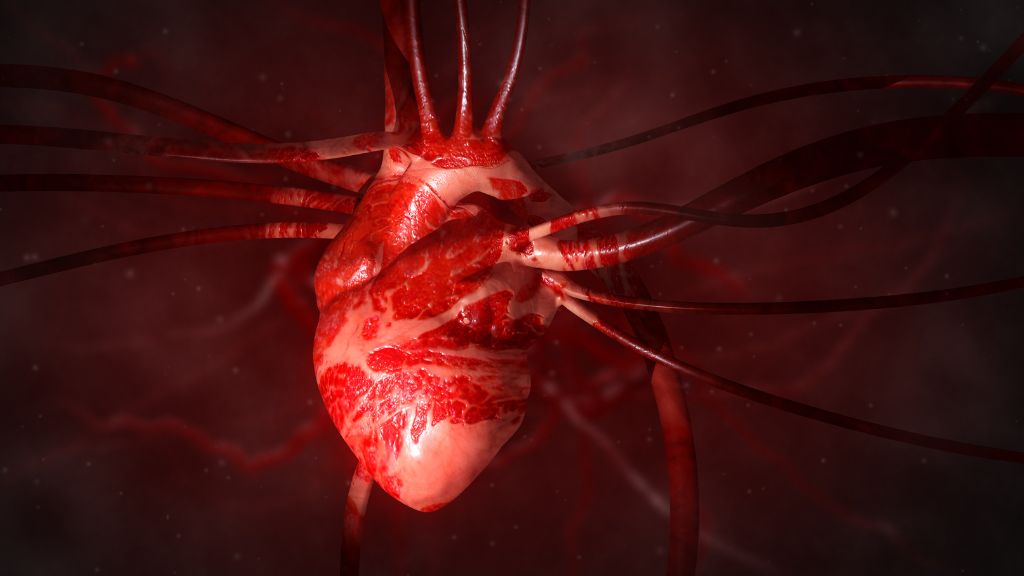

Oxytocin, sometimes called the "love hormone," may help heal broken hearts — literally. In a new study of zebrafish and human cells, scientists found that the brain-made hormone may help heart tissue regenerate after injury and, in theory, could someday be used in the treatment of heart attacks, according to the researchers.

Because the new study was conducted in fish tanks and lab dishes, however, this theoretical treatment is still far from realization.

Oxytocin has been nicknamed the "love" or "cuddle" hormone for its known role in forging social bonds and trust between people, and its levels often rise when people cuddle, have sex or orgasm. However, the so-called love hormone also serves many other functions in the body, such as triggering contractions during childbirth and promoting lactation afterward. Oxytocin also helps guard the cardiovascular system from injury by lowering blood pressure, reducing inflammation and diffusing free radicals, a reactive byproduct of normal cell metabolism, according to a 2020 review in the journal Frontiers in Psychology.

The new study, published Friday (Sept. 30) in the journal Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, highlights yet another potential benefit of oxytocin: At least in zebrafish, the hormone helps the heart replace injured and dead cardiomyocytes, the muscle cells that power heart contractions. Early results in human cells hint that oxytocin could stimulate similar effects in people, if delivered with the right timing and dose.

Related: Staying hydrated may reduce the risk of heart failure

The heart has a very limited ability to repair or replace damaged or dead tissue, the study authors noted in their report. But several studies suggest that after an injury, like a heart attack, a subset of cells in the heart's outermost membrane, called the epicardium, don a new identity. These cells migrate down into the layer of heart tissue where muscles reside and transform into stem-like cells, which can then turn into several heart cells types, including cardiomyocytes.

This process has largely been studied in animals and there's some evidence to suggest that it may also occur in adult humans. Unfortunately, if the process does occur in people, it seems to unfold too inefficiently and in too few cells to result in meaningful tissue regeneration after a heart attack, the study authors said in a statement. By somehow encouraging more epicardial cells to morph into cardiomyocytes, the authors theorize, scientists could help the heart rebuild itself after injury.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The study authors found they could jump-start this process in human cells in a lab dish by exposing them to oxytocin. They also tested 14 other brain-made hormones, but none of the others could coax the cells into the desired stem-like state required to make new cardiomyocytes, according to the statement.

The team then conducted follow-up experiments in zebrafish, a fish in the minnow family known for its impressive ability to regenerate tissues in its body, including the brain, bones and heart. The team found that, within three days of a cardiac injury, the fishes' brains began pumping out oxytocin like mad, producing up to 20 times more than they had prior to the injury, the team found. The hormone then traveled to the heart, plugged into its receptors and kicked off the process of transforming epicardial cells into new cardiomyocytes.

These experiments provide early hints that oxytocin may play a key role in heart repair after injury, and by boosting its effects, scientists could develop new treatments to improve patients' recovery after heart attacks and reduce the risk of future heart failure, the authors concluded. These treatments might include drugs that contain oxytocin or other molecules that can plug into the hormone's receptors.

"Next, we need to look at oxytocin in humans after cardiac injury," senior author Aitor Aguirre, an assistant professor in the Michigan State University Department of Biomedical Engineering, said in the statement. "Overall, pre-clinical trials in animals and clinical trials in humans are necessary to move forward."

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus