What is ozone?

Filling in the gap.

Ozone is a pale blue gas composed of three oxygen atoms bonded together. It occurs naturally high up in the Earth's atmosphere, where it protects the surface from harmful ultraviolet (UV) rays unless dissipated by natural or human phenomena. It is also considered a pollutant with adverse effects for humans and other creatures when present closer to the ground.

Oxygen vs. ozone

Molecular oxygen (O2) is the normal oxygen we breathe and is present throughout the atmosphere. It can be split apart by the sun's rays into two single oxygen atoms and one of these can then recombine with an O2 molecule to form O3, ozone, according to NASA.

The gas has a distinctive and sharp odor reminiscent of chlorine, and can sometimes be smelled after a thunderstorm, when lightning zaps oxygen molecules apart. This property is what gives ozone its name, after the Greek word ozein, meaning "to smell," according to an article published by the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.

Related: Trees: Unlikely culprits in ozone pollution

The vast majority of ozone sits in the stratosphere, an atmospheric layer between six and 31 miles (10 to 50 kilometers) above our planet's surface. Ozone makes up roughly 0.00006% of the atmosphere and peak concentrations of it are present at 20 miles (32 km) above the surface, in an area known as the ozone layer, according to NASA.

At that height, ozone absorbs intense UV radiation streaming in from the sun. Without this layer, the ground on Earth would be sterilized and life as we know it wouldn't be possible.

Earth's delicate ozone layer

Ozone is a relatively unstable substance and can be destroyed by molecules containing nitrogen, hydrogen, chlorine or bromine, which rip ozone's third oxygen atom away from its two partners. Starting in the 1950s, scientists began measuring ozone concentrations above Antarctica, giving them their first hints that there was a problem with the ozone layer.

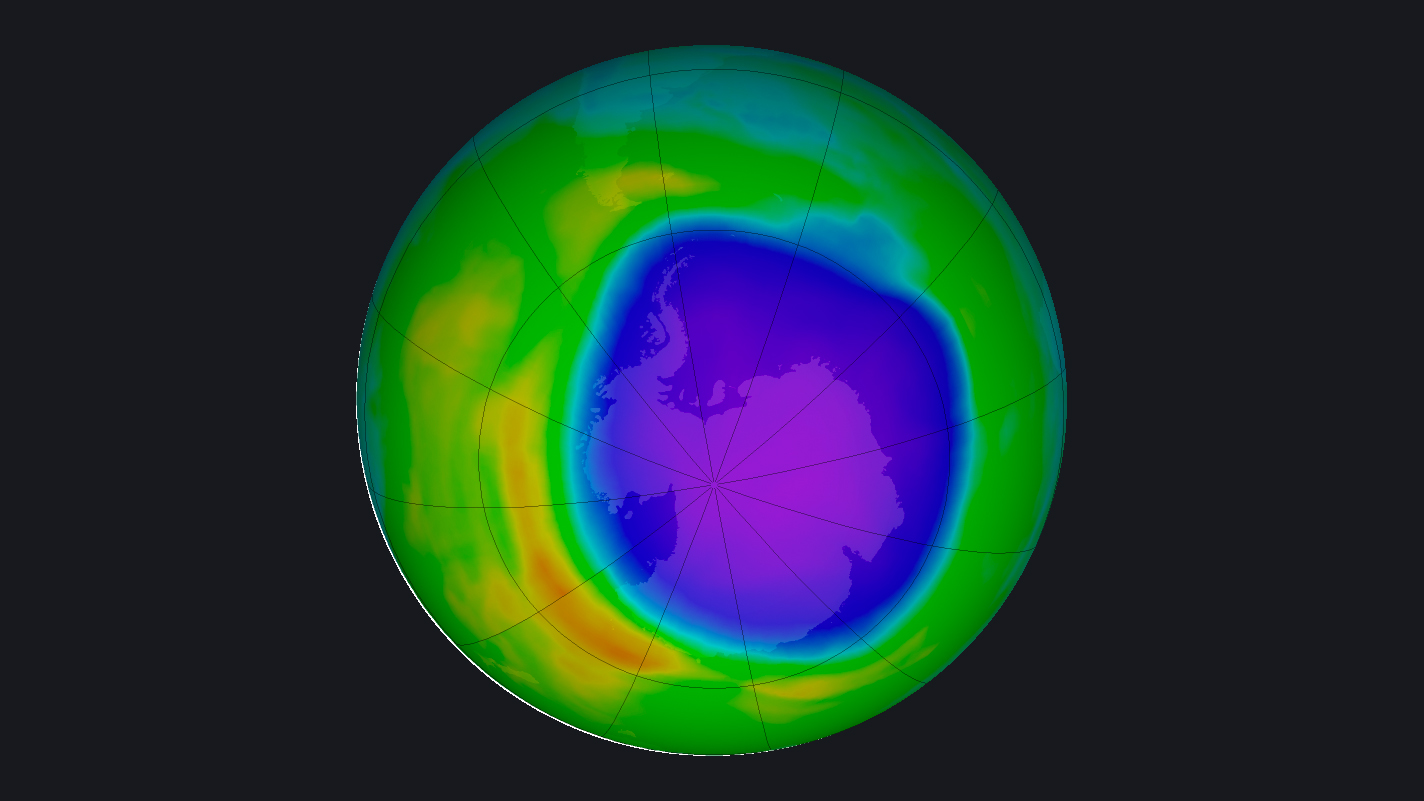

By the 1980s, researchers were able to map a yearly hole that opened in the ozone layer over Antarctica in the spring, though nobody knew its cause. In 1987, aircraft observations provided unassailable evidence that the ozone hole was being created by human-made pollutants called chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), according to a history from NASA.

Related: There's no good explanation for why ozone-ripping CFCs are back

Chlorine and bromine, which are present in chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and related compounds, are highly destructive to ozone. A single chlorine atom can rupture more than 100,000 ozone molecules before it leaves the stratosphere, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

CFCs come from industrial processes like refrigeration and are used in fire suppression and foam insulation, among other applications. Scientists were able to find that ozone depletion wasn't just occurring over the South Pole but also in areas over North America, Europe, Asia and much of Africa, Australia and South America.

In 1987, countries around the world signed the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer, an international document committing signatories to addressing the ozone hole, according to the EPA. People have been trying to phase out CFCs and other harmful industrial pollutants ever since.

Related: Banned ozone-depleting chemical was used illegally in China

Such efforts have paid off. A recent study showed that, between 2005 and 2016, there was a 20% drop in the amount of ozone being destroyed by chlorine.

In 2019, the ozone hole over Antarctica shrank to its smallest recorded size since it was discovered. There are still seasonal fluctuations in the South Pole hole as well as a similar one over the Arctic.

But in 2020, the North Pole ozone hole, which opens up more rarely than its southern cousin, reached its biggest known extent, somewhat concerning scientists. The unprecedented event came to an end a couple weeks later on its own, though researchers don't yet know if this new phenomenon will become a regular trend.

Ozone polluting Earth's surface

When ozone is present down near the ground, it can be harmful. Such ozone, also called smog, is created from oxides of nitrogen (NOX) emitted by cars, power plants, industrial boilers, refineries, and chemical plants combining with other organic molecules in the atmosphere, according to the EPA.

Breathing ozone can cause chest pain, throat irritation, coughing and harm lung tissue. It is most dangerous to children and the elderly and those with pulmonary issues like asthma, emphysema and bronchitis. It is also harmful to vegetation and affects forests, parks and wilderness areas.

Ozone is listed as a common pollutant in the U.S. Clean Air Act. The EPA offers an online Air Quality tool to tell people when pollution levels, including those from ozone, are spiking in their area.

Related: 'The Blob' in Pacific Ocean linked to spike in ozone

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that people spend more time indoors when ozone levels are high, choose less strenuous outdoor activities and plan to leave the house in the morning and evening, when ozone concentrations are usually lower.

The EPA has instituted national air quality standards that try to reduce ground level ozone by limiting the amount of pollutants coming out of cars and factories. The agency also recommends walking, biking and using public transportation when possible, reducing the use of air conditioners when ozone is high, and figuring out ways to be more environmentally friendly around the house.

Additional resources:

- Find more basic facts about ozone from the EPA.

- Read more about the Montreal Protocol, also from the EPA.

- Learn about the unhealthy effects of smog from the American Lung Association.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Adam Mann is a freelance journalist with over a decade of experience, specializing in astronomy and physics stories. He has a bachelor's degree in astrophysics from UC Berkeley. His work has appeared in the New Yorker, New York Times, National Geographic, Wall Street Journal, Wired, Nature, Science, and many other places. He lives in Oakland, California, where he enjoys riding his bike.