Women Missing Brain's Olfactory Bulbs Can Still Smell, Puzzling Scientists

Researchers have discovered a small group of people that seem to defy medical science.

The 29-year-old woman's brain scan was puzzling to say the least: It revealed she was missing brain structures she needed to be able to smell, yet she could sniff out odors even better than the average person.

It turns out, she's not the only one with this mysterious ability, according to a new study published today (Nov. 6) in the journal Neuron. Researchers have discovered a small group of people that seem to defy medical science: They can smell despite lacking "olfactory bulbs," the region in the front of the brain that processes information about smells from the nose. It's not clear how they are able to do this, but the findings suggest that the human brain may have a greater ability to adapt than previously thought.

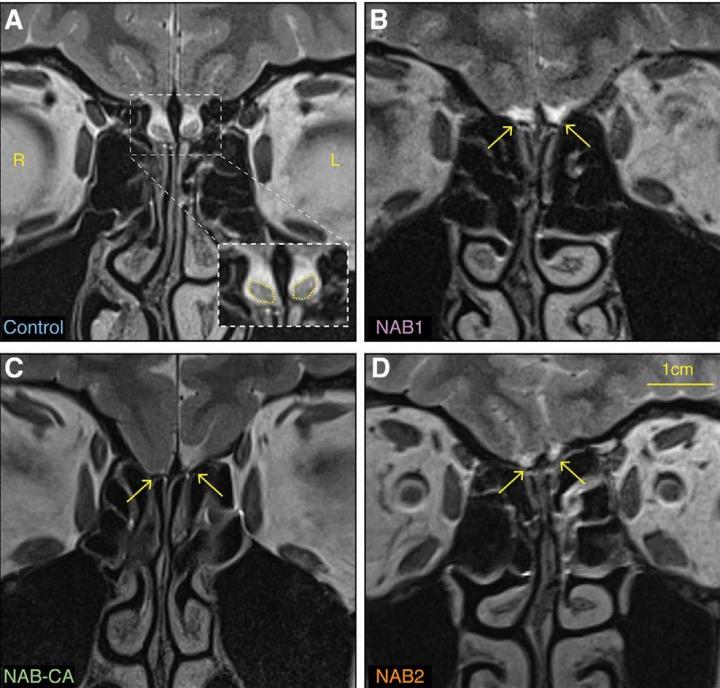

A group of researchers in Israel made this discovery by chance: They were conducting a different study that involved imaging the brains of patients with a normal sense of smell using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). But they noticed that one woman seemed to be missing her olfactory bulbs.

The scientists thought this was surprising because the ad for their study had noted participants should have a good sense of smell, and yet, based on her brain scan, the woman shouldn't be able to smell. The researchers thought "maybe she didn't notice" that part of the ad, said senior author Noam Sobel, a professor of neurobiology at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel. But when they asked her, she said she had a very good sense of smell.

Related:10 Things We Learned About the Brain in 2018

So Sobel and his team asked if they could conduct more scans and tests on her and found that indeed, she had a sense of smell slightly better than the average person. "Our understanding is that odors are essentially mapped on the surface of the bulbs," and the brain somehow reads this map, Sobel told Live Science. If you lack this map, you should also lack the ability to smell, he added.

Deciding to pursue this further, the researchers recruited more people as "controls" to compare with the unusual case. All of these controls were women and all left-handed like the original subject. "Lo and behold," in the ninth scan of a control "we discovered another woman without olfactory bulbs and a perfect sense of smell," Sobel said. At that point, "it started to look like no coincidence."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Fingerprint of the world's smells

The group then decided to search through a database called the Human Connectome Project that had published over 1,100 MRI scans, along with information about the participants' sense of smell. The researchers found that out of 606 women, three of them didn't have olfactory bulbs, yet they retained the ability to smell (and one of the three was left-handed).

They performed even more brain scans and smell tests on the two women, and one other woman who was also missing her olfactory bulb but could not smell. This third subject had what's called congenital anosmia, or a lifelong inability to smell. As expected, they found that the woman who had congenital anosmia couldn't smell most odors, while the other two women could smell as well as people with olfactory bulbs.

As a final step, the researchers wanted to create an "olfactory perceptual fingerprint" that documented what the world smells like to these participants. To do that, they asked the women and 140 other similarly aged women to rate how similar two smells were to each other, such as a lemon and an orange, or a lemon and a skunk. The fingerprints of the two women without olfactory bulbs were comparable to the fingerprints of the rest of the participants. What's more, the fingerprints of the two women were closer to each other than any other two participants.

There were slight differences, however. For example, neither of them could detect a rose-like odor, which is one of the most common odors in olfactory testing, said John McGann, an associate professor in the psychology department of Rutgers University who wasn't part of the study.

"It is surprising, it's not quite entirely shocking because there had been a previous report that sort of credibly showed one person who seemed to be able to have some sense of smell," without having an olfactory bulb, he told Live Science. (That study was published in 2009 in the American Journal of Rhinology). But that subject's sense of smell, in comparison to these new subjects, wasn't that great. So this study is a "stronger and compelling demonstration" that proves "it is possible somehow for some people to have a sense of smell despite not having olfactory bulbs," McGann said.

In the '80s and '90s, there were studies done on rodents that suggested if they had their olfactory bulbs removed they were still able to smell. But "those studies [were] pretty much ripped apart by our field; they were really hammered" for methodological problems, Sobel said. "Who knows, maybe now I'll be torn apart as well," he said. That's because their finding goes against dogma — the textbook definition of olfactory bulbs says they are "utterly essential" to the sensory system, he added. So what's going on?

The brain's nose

It's not clear why this ability was found only in women, specifically in left-handed women. Most brain-scan studies exclude participants who are left-handed to reduce variation among participants, which could be a reason why this wasn't found before, Sobel said. That's because people who are right-handed can have their brains wired differently than those who are left-handed.

It's also unclear how these women developed the sense of smell in their brains without having olfactory bulbs. But there are a couple of hypotheses that can explain what's happening, Sobel said. The first is that these women were born without olfactory bulbs and then somehow, as their brains developed in infancy, they found a way to make smell work, which would attest to how "plastic" the brain is, he said. In other words, another region of the brain might have taken on the task of transmitting scent information to the brain.

The sort of more exciting alternative might be that "you don't need olfactory bulbs" to detect, discriminate and identify smells, he said. That means that olfaction works very differently than we think and the olfactory bulb is doing something else, he added. For example, most mammals when they smell something have to make two decisions — what the smell is and where it's coming from. Maybe the olfactory bulb serves to figure out where the odor is coming from but not what the odor is, he said. But this is all speculative and needs to be tested, he added.

Thomas Cleland, the associate chair and professor in the department of psychology at Cornell University who was also not part of the study, says he thinks it's unlikely that the nerves that make up the olfactory bulbs are actually missing in these patients. "It’s more likely that the relevant circuitry, or something resembling it, is somehow misplaced, internally anatomically disorganized, and/or differently shaped, as opposed to being genuinely absent," he told Live Science in an email. "And if this is true, it’s not that strange that these women can smell somewhat normally."

But if there is some sort of displaced structure, "you'd expect that there would be some anomaly in their scan somewhere," said Joel Mainland, an associate member of the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia, who was also not a part of the study. "The idea that maybe there's a different structure that's [taking] over the role of the olfactory bulb would be surprising and amazing."

The findings are "pretty counter to most of what the field thinks," Mainland told Live Science. "I think it's pretty critical that we figure out what's happening."

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.