Pearl Harbor: Surprise attack that brought US into World War II

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii brought the US into World War II.

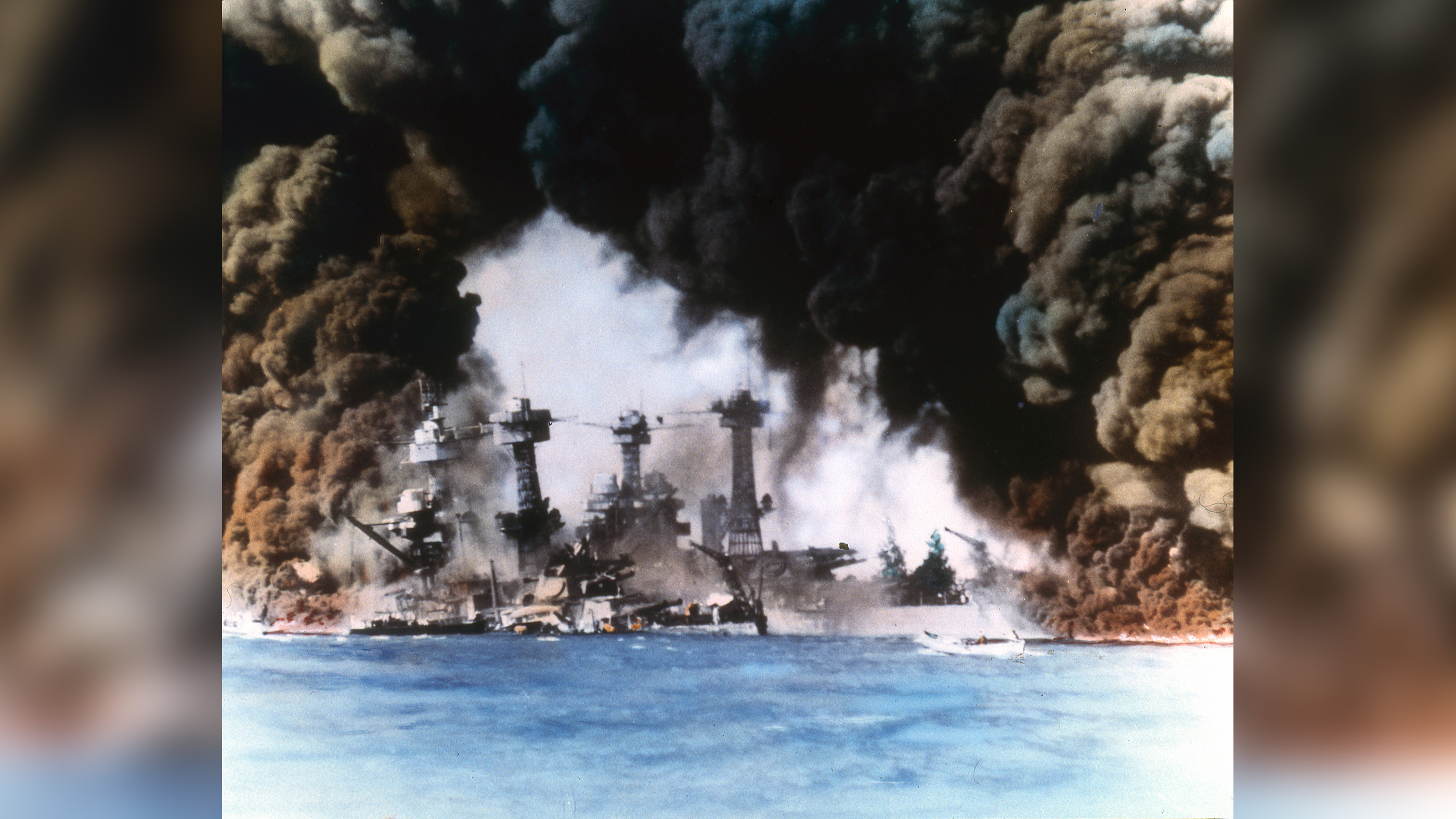

Pearl Harbor was a U.S. naval base that was bombed by the Empire of Japan in a surprise attack, precipating America's full-scale involvement in World War II. Taking place on Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy sent aircraft to strikeships and installations of the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Ships and service people at Pearl Harbor were not the only ones attacked on Dec. 7 as military installations on the island of Oahu and elsewhere were also targeted during the attack.

The sudden air assault devastated American naval power in the region and triggered the U.S. entry into World War II, beginning the Pacific War. The next day, President Franklin Roosevelt called Dec. 7 "a date of infamy," in a speech to Congress, according to the U.S. Library of Congress. American entry into World War II is seen as a major turning point in the conflict against the Axis powers of Nazi Germany, Italy and Imperial Japan.

What led to the Pearl Harbor attack?

The attack on Pearl Harbor followed months of negotiations between the Japanese and U.S. governments, which had failed. During the previous decade, Japan had sought to expand its territory in the Pacific and on the Asian mainland to secure land and natural resources, according to Mark Stille, an historian and author of "The United States Navy in World War II" (Osprey, 2021).

Japan had been at war with China since 1937, which affected U.S. relations with both nations, according to the U.S. Office of the Historian. In 1940, Japanese forces occupied French Indochina (modern-day Vietnam), and the U.S., Britain and its allies responded by placing a trade embargo on Japan. This caused huge damage to the Japanese economy. "In particular, Japanese low oil reserves meant that action had to be taken before the Imperial Navy was crippled through lack of fuel," Stille told Live Science. "The Japanese chose to double down on aggression after being called to account for their expansionist policies."

"For Japan, Pearl Harbor was really the sideshow – they were trying to get rid of the US fleet of ships and attempting to stop supplies to the British. It was not about taking Hawaii. Their interest was in expanding to Southeast Asia and removing the Western powers," Robert Cribb, professor of Political and Social Change at Australian National University, told All About History in 2015.

In the summer of 1941, the U.S. issued a series of further economic sanctions and an ultimatum for Japan to withdraw its troops from French Indochina. This led the Japanese government to conclude that war with the U.S. was the only option available.

Japanese attack plan

The attack on Pearl Harbor was planned by Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander in chief of the Combined Fleet. Yamamoto was a naval aviator and had studied at Harvard University. He had also been posted to the Japanese Embassy in Washington, D.C., in the 1920s.

When considering a possible war with the U.S., Yamamoto remarked: "If I am told to fight, regardless of the consequences, I shall run wild for the first six months or a year, but I have utterly no confidence for the second or third year," according to James B. Wood's book "Japanese Military Strategy in the Pacific War" (Rowman & Littlefield, 2007).

"There is only one reason why the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor: because [commander in chief of Japan’s Combined Fleet] Yamamoto Isoroku thought it would be a good idea. Without Isoroku’s vision and determination to pull off the attack, it would never have occurred. Apparently, he actually believed that the loss of several battleships would shock the Americans into making peace," Stille said.

Yamamoto ordered Lt. Cmdr. Minoru Genda to formulate a plan of attack for the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN), while Capt. Mitsuo Fuchida was chosen to command the air assault. On Nov. 26, 1941, under strict radio silence, the six aircraft carriers of the Japanese First Air Fleet — called Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, Hiryu, Shokaku and Zuikaku — departed home waters. They were escorted by an armada of 31 warships and support vessels.

The attack was planned in two waves of fighter and fighter-bomber aircraft, totaling 353 aircraft. They were targeting six U.S. Navy battleships moored along Battleship Row at the eastern end of Ford Island. These ships included the USS Oklahoma, Maryland, West Virginia, Tennessee, Arizona and Nevada, as well as the USS California lying nearby and the USS Pennsylvania in Drydock 1 across the harbor.

"Of course, the American level of preparedness was woefully inadequate. The reasons behind this are many, but the primary one was a lack of understanding of what the Imperial Japanese Navy was capable of," Stille said. "The Americans failed to understand that the Japanese had a viable method to deliver a serious blow against the Pacific Fleet in Hawaii."

Japanese war machines

What happened at Pearl Harbor?

The attack on Pearl Harbor began at around 7:55 a.m local time when the first wave of Japanese aircraft reached their targets. Positioned 230 miles (370 kilometers) north of Oahu, the Japanese carrier fleet launched 185 aircraft, according to "Sunday in Hell Pearl Harbor Minute by Minute," by Bill McWilliams (Open Road Media, 2014).

The first wave included 43 fighter planes sent to protect the bombers and torpedo-bombers. These fighters also attacked airfields and barracks with machine-gun and cannon fire, disabling almost all U.S. aircraft and preventing them from taking off.

Lt. Cmdr. Fuchida, the leader of the attack, reported the completion of the surprise attack by sending a radio message to the fleet: "Tora! Tora! Tora!" Translated from Japanese to English, the word means "Tiger," according to McWilliams. After bombs fell on Ford Island Naval Air Station, at the center of Pearl Harbor, Lt. Cmdr. Logan Ramsey sent out the emergency message: “Air raid Pearl Harbor. This is no drill."

Five of the ships on Battleship Row were severely damaged during the first wave of the attack, including the USS Arizona, which exploded after receiving a direct hit. The battleship sank in minutes, with the loss of over 1,100 crewmen according to PearlHarbor.org.

Despite several warnings, American forces in Hawaii, under Adm. Husband E. Kimmel and Gen. Walter Short, were unprepared for the attack. They had ignored early sightings of submarines in the area around Pearl Harbor. They also ignored radar detection of the first wave of the Japanese airborne attack; a warning from Washington, D.C., was received too late.

The second wave of 167 aircraft launched from their carriers at 7.25 a.m. local time, 90 minutes after the first wave departed, according to McWilliams. These aircraft targeted the remaining ships in Battleship Row, including USS Pennsylvania. Those aircraft returned to their carriers around 9.50 a.m.

Aftermath of the Pearl Harbor attack

Along with the loss of the USS Arizona, torpedo damage also capsized Oklahoma, and West Virginia also sank. Every other battleship in the harbor, as well as several U.S. cruisers and destroyers were badly damaged. A total of 2,403 Americans were killed in the attack, while the Japanese lost 29 planes and five submarines.

"The Americans should have been expecting a Japanese attack, but they were more concerned with sabotage," David Kilton, chief of interpretation at the Pearl Harbor National Memorial, told History of War magazine. "There were several cues, but none of them resulted in action before the Japanese attack."

In addition to the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese inflicted heavy damage on other naval, marine and army installations at Kaneohe Naval Air Station, Hickam Field, Wheeler Field, Bellows Field and Ewa Marine Corps Air Station. "Overall, the Japanese attack was very successful," Kilton said. "The Japanese struck with total surprise, and all their worries concerning secrecy were overcome."

However, Kilton argues that the Japanese attack could have been even more effective, as it failed to damage any significant infrastructure targets such as drydocks, oil reserves and other similar targets. "This might have decimated us more severely and taken the U.S. more time to get back on its feet and engage the Japanese as quickly as we did," he said. "Japan showed how effective air power could be in striking a target and being successful. The loss of capital ships forced us to use carriers in that way."

The carriers USS Lexington, Enterprise and Saratoga, were operating at sea at the time of the attack, and were undamaged. They later became the cornerstone of the U.S. Navy’s recovery and retaliation.

Pearl Harbor attack map

U.S. enters WWII

Nevertheless, the attack on Pearl Harbor shocked the American public and triggered an increase in support for the war. "The United States was a politically divided country prior to Pearl Harbor," said Patrick K. O’Donnell, author of "Into the Rising Sun," a collection of oral histories from veterans of WWII, in a telephone interview. "Pearl Harbor galvanized America in the war effort like few other events could have done."

"It was the beginning of the concept of the ‘greatest generation’. The American people rose to the challenge that was before them. Not every decision made was a good decision, but everybody mobilised in some way. Even the media generated advertising stuff, and the recycling of cans for making equipment we needed for the war effort took hold. It was a full-hearted response," Kilton said.

Salvage operations began immediately after the Japanese planes had departed Hawaiian airspace, and the Herculean task required years to complete. Meanwhile, just six months after the attack, the U.S. Navy inflicted a terrible defeat on Yamamoto and the Japanese fleet at the Battle of Midway, the turning point of World War II in the Pacific.

"The attack on Pearl Harbor was the seminal event of the Second World War. It brought the full power of the United States into the war with enough time to shape the outcome of the war. It virtually guaranteed that the Americans would fight the war to the finish. For the Japanese, Pearl Harbor was the ultimate folly. It undermined their vague notion that the United States would succumb to war weariness and lead to a negotiated settlement. Not only was it the epitome of poor strategic planning, but it provided little military advantage to the Imperial Navy as it opened the conflict," Stille said.

A number of the ships damaged at Pearl Harbor were repaired, modernized and returned to service. The USS Arizona, however, was beyond repair, and the sunken battleship remains where it was moored. In 1962, a memorial was dedicated to the USS Arizona, right above where the ship had sunk. Each year on Dec. 7, the United States remembers the fateful Japanese attack as Pearl Harbor Day. "You can still see the scars of the attack 80 years later, and we need to never forget the lessons we have learned as we make decisions today," Kilton said. "That’s part of the mission of the National Park Service here at Pearl Harbor — to remember."

Additional resources

If you want to dig deeper into the story of Pearl Harbor then you should read about the 9 mysteries of the attack that can now be explained.

And while Pearl Harbor was a particularly deadly day for the United States of America, was it the deadliest? Find out with our list of deadliest days in U.S. history.

Bibliography

- "Speech by Franklin D. Roosevelt, New York (Transcript)" U.S. Library of Congress

- "The United States Navy in World War II" by Mark Stille (Osprey, 2021)

- "Japan, China, the United States and the Road to Pearl Harbor, 1937–41" U.S. Office of the Historian

- "Japanese Military Strategy in the Pacific War" by James B. Wood (Rowman & Littlefield, 2007)

- "Sunday in Hell Pearl Harbor Minute by Minute" by Bill McWilliams (Open Road Media, 2014)

- PearlHarbor.org

- Pearl Harbor National Memorial

- "Into the Rising Sun" by Patrick K. O’Donnell (The Free Press, 2002)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Michael E. Haskew, who has been studying military history for more than 25 years, is the Editor of WWII History magazine and The World War II Desk Reference with the Eisenhower Center for American Studies. He is also the author of several books, including the "West Point 1915: Eisenhower, Bradley, and the Class the Stars Fell On," "Appomattox: The Last Days of Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginias," and "Tank: 100 Years of the World's Most Important Armored Military Vehicle."