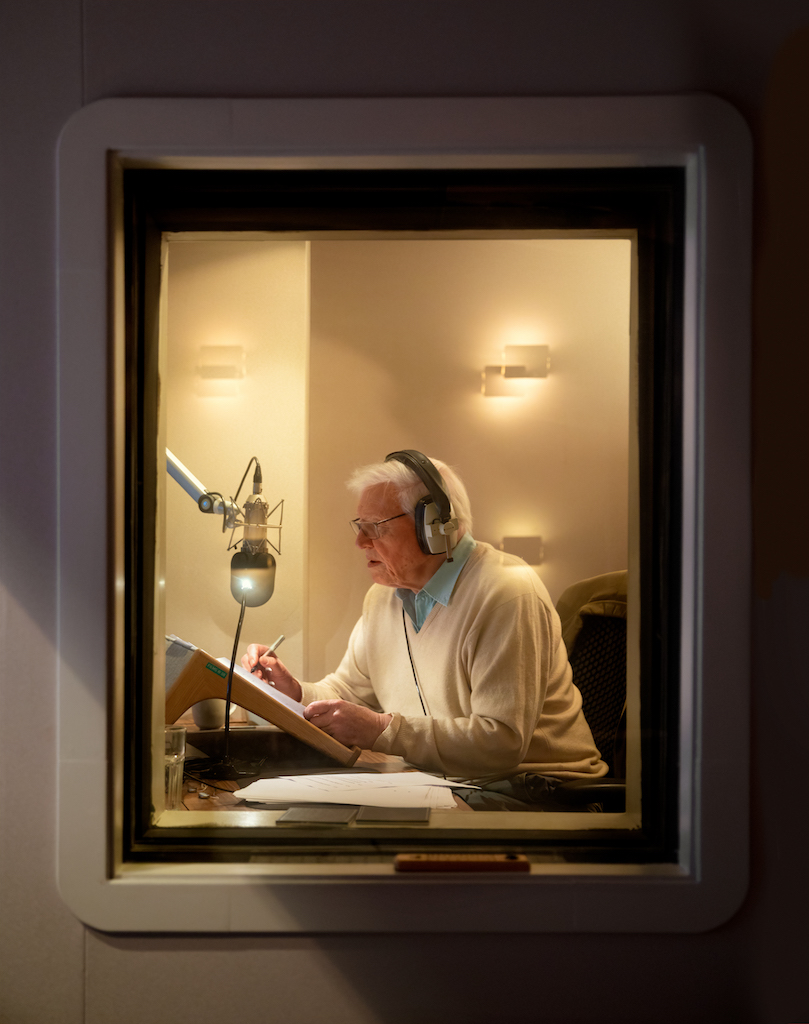

Humans are destroying our 'perfect planet,' Attenborough says

A new series explores how natural forces come together to support life on our planet, and how humans have become a new force that's destroying it.

Powerful natural forces on our planet and in our solar system work together to sculpt and support life on our fragile pale blue dot.

A new five-part series called "A Perfect Planet," narrated by the legendary Sir David Attenborough, explores how these natural forces have worked together to make life possible — and how a fifth force, humans, are destroying this perfection at breakneck speed.

The planet is at a "crucial point" and "poised" for really big disasters, Attenborough said during a question and answer session on Nov. 23. "We can stop them, but if we're going to stop them," he added, we need to understand what forces are driving these disasters and how those forces work.

Related: 50 interesting facts about planet Earth

The series, which took about five years to research and film, brings viewers to various spots across the globe to tell stories of four natural forces — oceans, sun, weather systems and volcanoes — that have dramatically shaped our planet. In the first episode, for example, the series focuses on volcanoes — one of the most destructive forces of nature but one that's vital for life on our planet.

On the northern side of the Ol Doinyo Lengai volcano in Tanzania, one of Africa's most active volcanoes, sits Lake Natron, one of the world's most corrosive bodies of water. And yet, this seemingly inhospitable environment is crucial for the survival of one species.

Millions of lesser flamingos (Phoeniconaias minor) fly in from East Africa to breed on islands of salt that emerge within the lake when scalding hot temperatures evaporate the water. This environment is filled with "gloopy sulfurous mud" and has a pH that's "not far short of household bleach" and temperatures equivalent to "a scalding cup of tea," said wildlife cinematographer Matt Aeberhard. Yet the flamingos thrive there because the caustic soda in the lake makes it inaccessible to land-based predators.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It's also good at keeping humans out. A hazy mirage shrouds the lake, making it dangerous for helicopters and aircraft to land there, so the only way to reach the lake is via hovercraft, Aeberhard said. And you have to wear snowshoes, "which actually doesn't look that strange because Lake Natron, when you're out on the flat, is white, so it's almost like a crazy snowscape." The team also relied on drones for some of the incredible footage from that scene.

"This series is a celebration of the planet," said Huw Cordey, the series producer. "Now is as good a time as ever to really look and see how well everything fits together, how beautifully it's all connected."

The last episode takes a dramatic tone shift and Attenborough talks about how humans are now the dominant (and destructive) force of the planet and what we can do to diminish our influence. "It's just no longer enough to make pure celebratory natural history series, we have to tell a bigger story," said Alastair Fothergill, the executive producer of the show.

This series comes as our perfect planet roils under a deadly pandemic. "The remarkable thing about it is that it has made a lot of us actually suddenly become aware of the natural world in a way that we have not been before," Attenborough said, noting that he's never listened to more bird songs in his life. "We realize our dependency emotionally and intellectually on the natural world in a way that we've never done before."

The series is a Silverback Films Production for BBC and Discovery and will premiere on discovery+ on Jan. 4.

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.