Perseid meteor shower 2024: What it is, where to see it, and how to watch

Everything you need to know about August's prolific display of "shooting stars."

The Perseid meteor shower is the most famous annual display of "shooting stars." It typically occurs between July and August, when it's warm in the Northern Hemisphere. The Perseid meteor shower in 2024 peaks the night of Aug. 12 and in the pre-dawn hours of Aug. 13. Depending on conditions, it's an ideal time to plan camping trips, star parties and backyard stargazing sessions, but it pays to know exactly what to do and when to do it.

Here's everything you need to know about the Perseid meteor shower and how to watch it.

Where to see the Perseid meteor shower

The Perseid meteor shower is visible in the Northern Hemisphere down to the mid-southern latitudes. It's best viewed in a Dark Sky Place, or in areas outside of major cities, where light pollution won't drown out the stars.

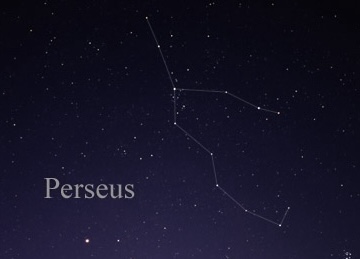

Though the Perseids are visible throughout the sky, they appear to originate from the Perseus constellation. For a better chance of seeing "shooting stars," find Perseus, which rises from the northeastern night sky in the Northern Hemisphere in August. This constellation can be a little tricky to spot, but you can use Cassiopeia, one of the brightest constellations in the sky, as a guide. Look for the "W" shape of Cassiopeia to the north, and Perseus will be nearby.

What is the Perseid meteor shower?

The Perseids are the most famous meteor shower of all. They appear between July 14 and Sept. 1 each year, peaking around Aug. 11, 12 or 13. All meteor showers have a night of peak activity when you can expect to see the most "shooting stars," but while some of these intervals can be very brief, the Perseids' peak is fairly prolonged. That's helpful, because if it's cloudy on the peak night, you can always look to the skies the night after. During the Perseids' peak, it's possible to see 100 meteors per hour, according to NASA.

How to watch the Perseid meteor shower

You need two things to see the Perseid meteor shower: good timing and good patience. You need to be outside just after midnight on the night of peak activity, and be prepared to do a late shift through 5 a.m. Clouds, a bright moon and light pollution are your enemies. Clouds aren't something you can change and the moon is also out of your control, but you can find a dark sky by visiting a Dark Sky Place or consulting a light pollution map.

Sit in a lawn chair or lay on a blanket on the ground and look up. Allow about 30 minutes for your eyes to adjust to the dark. "Shooting stars" from the Perseid meteor shower can appear anywhere in the night sky.

Telescopes and binoculars will make it hard to scan the sky and find the fleeting fireballs. That said, binoculars for stargazing and telescopes may be useful for other summer skywatching events, like upcoming planetary conjunctions and full moons.

One other thing: Don't look at your smartphone, because its white light interferes with night vision.

What are "shooting stars"?

Shooting stars are not really stars. Rather, they're tiny rock particles called meteoroids that strike Earth's atmosphere about 60 miles (97 kilometers) from the ground. As they do, they release energy as photons, or packets of light, that we call shooting stars. Meteoroids that enter Earth's atmosphere are called meteors, and they streak across the sky at blazing-fast speeds; the Perseids, for example, travel through the atmosphere at 133,200 mph (214,360 km/h), according to the American Meteor Society.

Meteor showers occur when our planet moves through a dense stream of dust and debris left in the inner solar system by a comet or, occasionally, an asteroid.

The Perseids and "fireballs"

If the moon is bright or you live in a region with high light pollution, don't give up on seeing the Perseids. This meteor shower often features bright "fireballs" that can cut through an illuminated night sky. Fortunately, in 2024, the Sturgeon supermoon won't occur until a week after the Perseids peak, keeping the sky relatively dark.

A fireball, or "bolide," is a large and very bright meteor — sometimes as bright as Venus — that is relatively rare but visible even in a night sky bleached by man-made light pollution or moonlight.

"The more particles released by the comet, the better chance that some of these will be large enough to produce fireballs," said Robert Lunsford, a fireball report coordinator at the American Meteor Society. "It's not the best fireball producer, but the Perseids is certainly one of the most reliable sources." Fireballs can have a tail that lasts about a second, making them an unforgettable sight.

What causes the Perseid meteor shower?

The dazzling light show is caused by comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle, which was last in the inner solar system in 1992 and won't return until 2126. Some comets (like Halley's comet) produce multiple meteor showers, but 109P/Swift-Tuttle produces only one. "The peak occurs when the Earth passes closest to the core of the many comet orbits produced by 109P/Swift-Tuttle as it passes through the inner solar system," Lunsford told Live Science. "We rarely strike one of these debris streams exactly — and if we do, rates will be stronger than normal."

Why the Perseid meteor shower is so well-known

The Perseids are certainly pretty, but their fame has more to do with their convenience than their numbers.

"It's strictly because they peak during the summertime for observers in the Northern Hemisphere," Lunsford said. "The other, stronger showers all occur in autumn/winter for the Northern Hemisphere." The most prolific meteor showers are the Geminids, which peak around Dec. 13 and 14, and the Quadrantids, which peak around Jan. 3 and 4. However, because of the cold conditions and reduced chance of a clear sky, far fewer folks attempt to watch these showers.

Why the Perseids are so prolific

According to the American Meteor Society, the maximum number of "shooting stars" that the Perseids typically deliver is about 100 per hour, though that's under a perfectly dark sky with a 360-degree view. But it's not uncommon to see 30 or so "shooting stars" per hour during the Perseids' peak night. The Perseids are so prolific because the parent body, comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle, has such a large nucleus, which measures 16 miles (26 km) in diameter.

"It has made many passes through the inner solar system, shedding a lot of debris that now populates the entire orbit of the comet," said Lunsford. "Because of this, each year is guaranteed to produce a decent display with little variation."

The Perseids won't change much in the 21st century, even though their parent body isn't set to return to the inner solar system for another 100 years. The intensity of the shower may wane by about 25% when the comet is farthest from the sun, but since material has spread throughout the entire orbit, the difference won't be that much, according to Lunsford.

Perseid meteor shower times in 2024, 2025 and 2026

Meteor showers all have times when the rate of activity peaks, but the exact time and date changes from year to year. That's because Earth takes 365.25 days to return to the exact same spot in its orbit.

"This extra .25 day adds six hours to the time of maximum activity," Lunsford said.

Lunsford says that extra fraction of a day causes the Perseid meteor shower to shift forward by six hours every year, though it snaps back a full day after a leap year. That means the Perseid maximum is predicted to occur at different times each year:

Still, predictions for the Perseid maximum may change over time, so check back every year to make sure they're still on track. "Observations of the peak times each year helps us determine a more precise prediction for following years,” says Lunsford.

Originally published on Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Jamie Carter is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor based in Cardiff, U.K. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners and lectures on astronomy and the natural world. Jamie regularly writes for Space.com, TechRadar.com, Forbes Science, BBC Wildlife magazine and Scientific American, and many others. He edits WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com.