Long-lost copy of Newton's famous book 'Opticks' to be auctioned for half a million dollars

The book is the pristine version of the two copies originally kept in Newton’s library

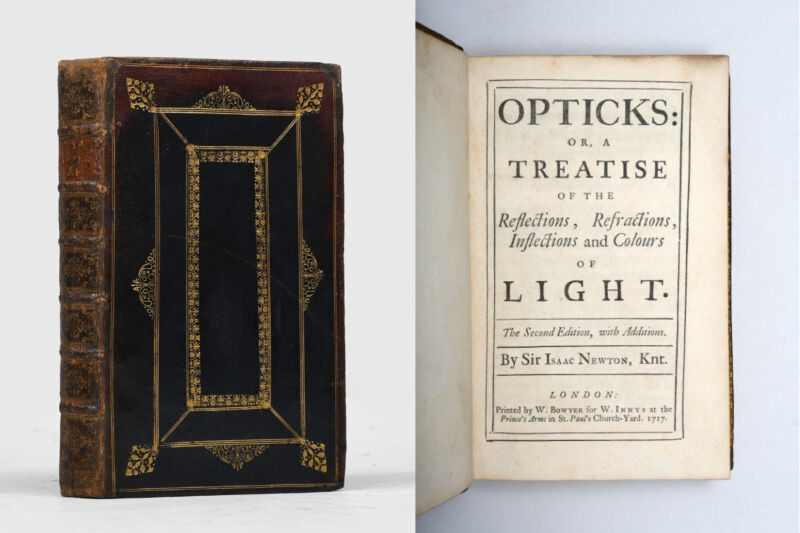

A pristine personal copy of Isaac Newton’s book "Opticks" that was recently found after going missing for a century is going up for auction.

Newton’s illuminating treatise analyzes the fundamental nature of light and is considered one of the Scientific Revolution’s three major works on optics. The long-lost copy was discovered by book collector David DiLaura while he was sorting his collection during the COVID-19 pandemic. The book is set to be sold at the Rare Books San Francisco Fair held on Feb. 3 to Feb. 5 and is expected to fetch the whopping price of $460,000.

While organizing his collection, DiLaura, a professor emeritus at the University of Colorado, found a copy of Newton’s Opticks that he had purchased 20 years before. Its bookplate indicated the book was a second edition printed in 1717 and previously owned by a man named James Musgrave. Closer inspection, however, revealed a second bookplate hidden by the first — revealing the previous owner was Charles Huggins.

Related: Newton's recipe for 'toad vomit lozenges' up for auction

By researching the two names, DiLaura learned that after Newton died without a will in 1727, his books and other possessions were purchased by an individual named John Huggins, who gave them as a gift to his son Charles, a rector in Oxfordshire. The items were handed down to Charles’ successor as rector, James Musgrave, and passed down for generations before a large number of the items were sold in 1920. The book was then considered lost until DiLaura’s discovery.

Newton’s Opticks was first published in 1704 and was the culmination of decades of the physicist’s investigations into the nature of light. Unlike his more famous "Principia Mathematica," which outlined the three laws of motion and was written in Latin, Newton wrote Opticks in popular, vernacular English, making it accessible to a wider audience.

Of the many discoveries detailed within its pages, Newton explained how glass prisms could both break white light down into and reconstitute it with the constituent colors of the optical spectrum; weighed in on the debate on whether light was a particle or a wave (he believed it was a particle, which he called a corpuscle); and described how our perception of color comes from the way a material selectively absorbs, transmits or reflects the different colors within white light.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Newton’s fascination with light and how we perceive it not only made his experiments painstaking, but painful too. As a young man, he stuck a long, blunt sewing needle (a bodkin) into his eye between the bone and the eyeball to poke at the retina underneath. By studying the glowing spots in his vision that the gruesome probing produced and comparing his notes to those taken from the dissection of a rabbit’s eye, Newton confirmed that the eye acted much like a pinhole camera — inverting images onto the retina wall that the brain would later revert to construct our sense of vision.

The copy of Opticks found by DiLaura is believed to be one of two personal editions originally belonging to Newton; it is the pristine counterpart to his working copy, which is brimming with annotations, edits and marginalia, and is kept in the Huntington Library’s collection. Personal copies and first editions of Newton’s books are incredibly rare and can be expected to sell at a high price. In 2016, a Latin first edition of Newton’s “Principia Mathematica” was sold at Christie’s in New York for $3.7 million to an undisclosed buyer, making it the most expensive scientific book ever sold at auction.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.