Photos: Squashed skull of 70,000-year-old Neanderthal discovered in cave

Shanidar Cave in Iraqi Kurdistan is a hotspot for Neanderthal remains.

Flattened skull

Archaeologists have discovered the torso and squashed skull of a Neanderthal who lived about 70,000 years ago in what is now Iraqi Kurdistan. Heavy sediment flattened the skull (shown here).

Related: Read the full story about the newly discovered Neanderthal remains

The map

This map shows the location of Shanidar Cave in Iraqi Kurdistan, where the Neanderthal remains were discovered.

Left hand

The bones of the Neanderthal's left hand, shown here partially excavated from the sediment in Shanidar Cave.

Ribs and spine

The ribs and spine of the ancient Neanderthal: Based on the worn teeth, the Neanderthal was likely a middle-age to older adult.

Shanidar Cave

The steep entrance to Shanidar Cave.

Amazing view

The view from Shanidar Cave, looking down on the valley of the Upper Zab River. This is the rugged landscape of northeastern Iraqi Kurdistan.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Left arm and ribs

The remains of the Neanderthal's left arm and ribs in Shanidar Cave.

Spinal cord

The delicate bones of the Neanderthal's spinal column: This specimen is now on loan at the University of Cambridge, where it is being CT scanned and conserved with a special glue that protects the bones.

Research in motion

Study co-lead researcher Emma Pomeroy takes a short break at Shanidar Cave.

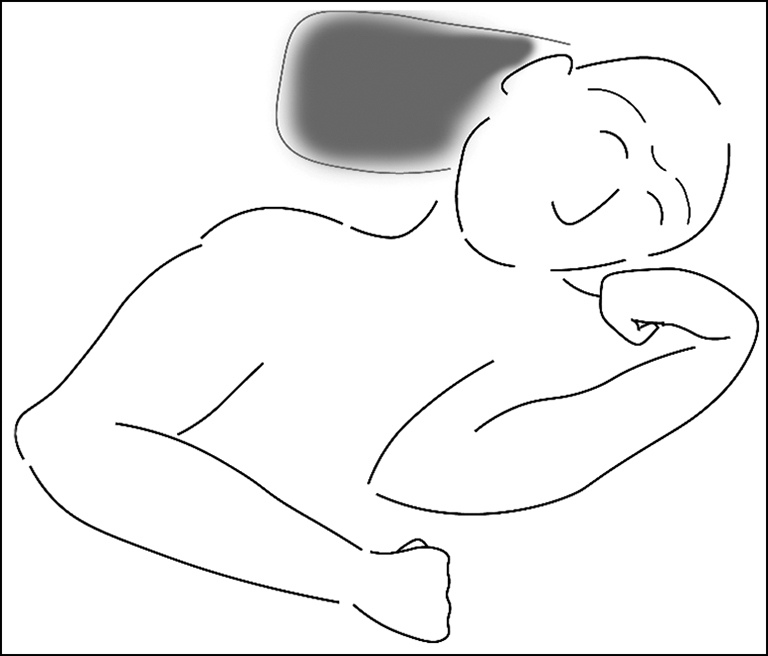

Neanderthal sketch

This illustration shows the possible burial position of the newly discovered Neanderthal, whose partial remains were found in Shanidar Cave. The gray stone behind the individual may be a grave marker.

Work site

Study senior author Graeme Barker, a professor in the Department of Archaeology at the University of Cambridge, sits in front of the newfound Neanderthal remains. Barker is holding a soil block that will be analyzed at Cambridge in England.

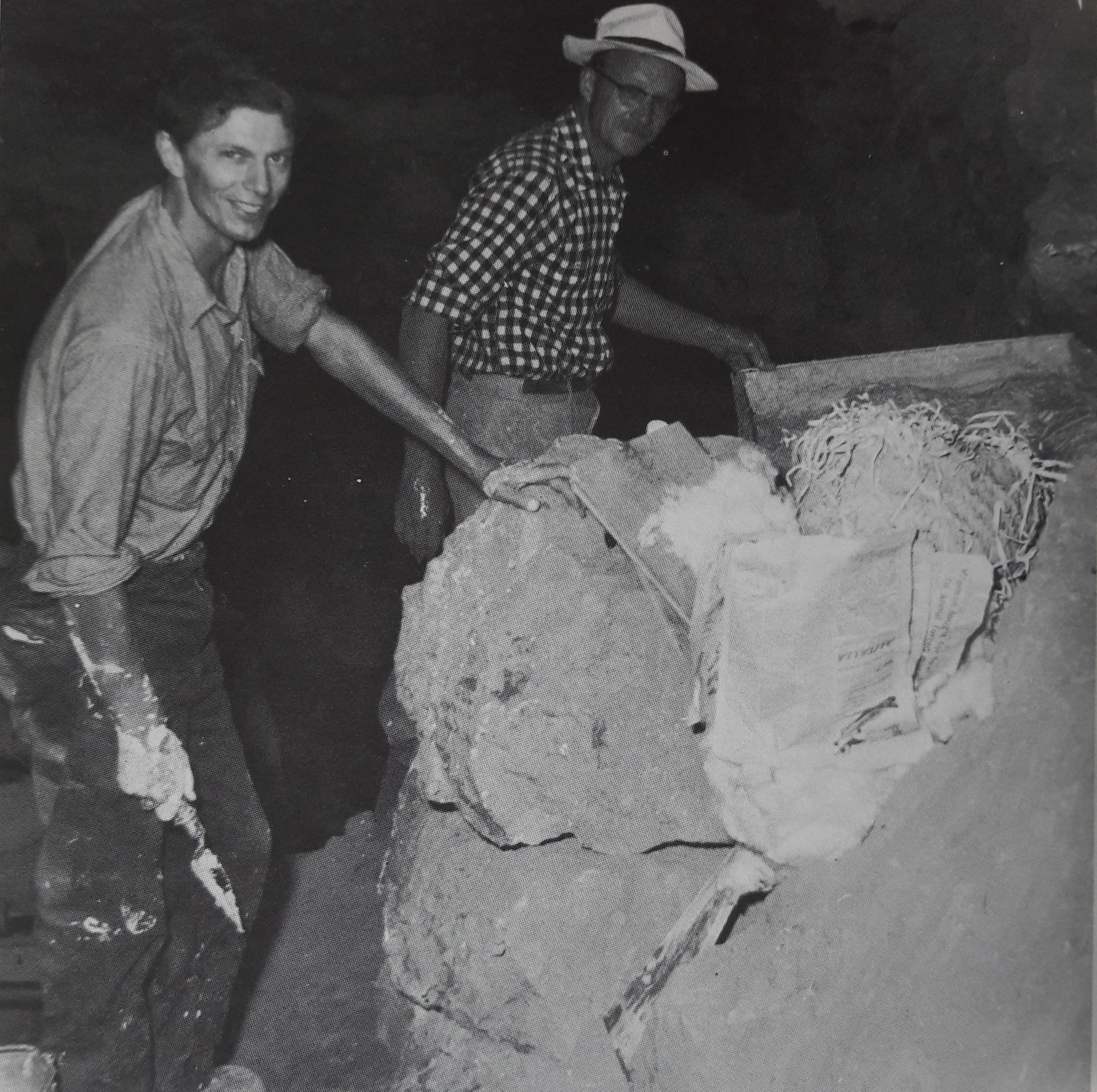

Initial excavation

Part of Ralph Solecki's team that excavated the remains of the 10 Neanderthal men, women and children who were discovered in Shanidar Cave in the 1950s. Here, T. Dale Stewart (right) and Jacques Bordaz (left) move the remains of the so-called "flower burial" "en bloc" ("all together") from the cave. This block was later found to hold the partial remains of three more Neanderthals.

Heavy work

Solecki's colleagues carry the block containing the "flower burial" down from the cave. This block was then placed on top of a taxi and driven to Baghdad Museum for further study.

Feature video

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.