Photos: Hidden Ruins of an Old Scottish Whisky Distillery

These ruined stone buildings hidden in the forest in the Scottish Highlands would have been an ideal site for making illicit whisky.

The old buildings, dating back to the 1700s, were almost forgotten until government agency Forest and Land Scotland planned to harvest trees in the area, near Loch Ard about 20 miles (32 kilometers) north of Glasgow.

A local history group told the agency about the ruined buildings, and a digital survey of the site was carried out.

Highland whisky

Making whisky from malted barley was a traditional farm activity in the Scottish Highlands.

But the government banned small whisky stills from the late 1700s and imposed heavy taxes designed to make money from the whisky trade. Many Highlanders responded by making whisky in illicit stills set up where the government couldn’t find them.

Government excisemen

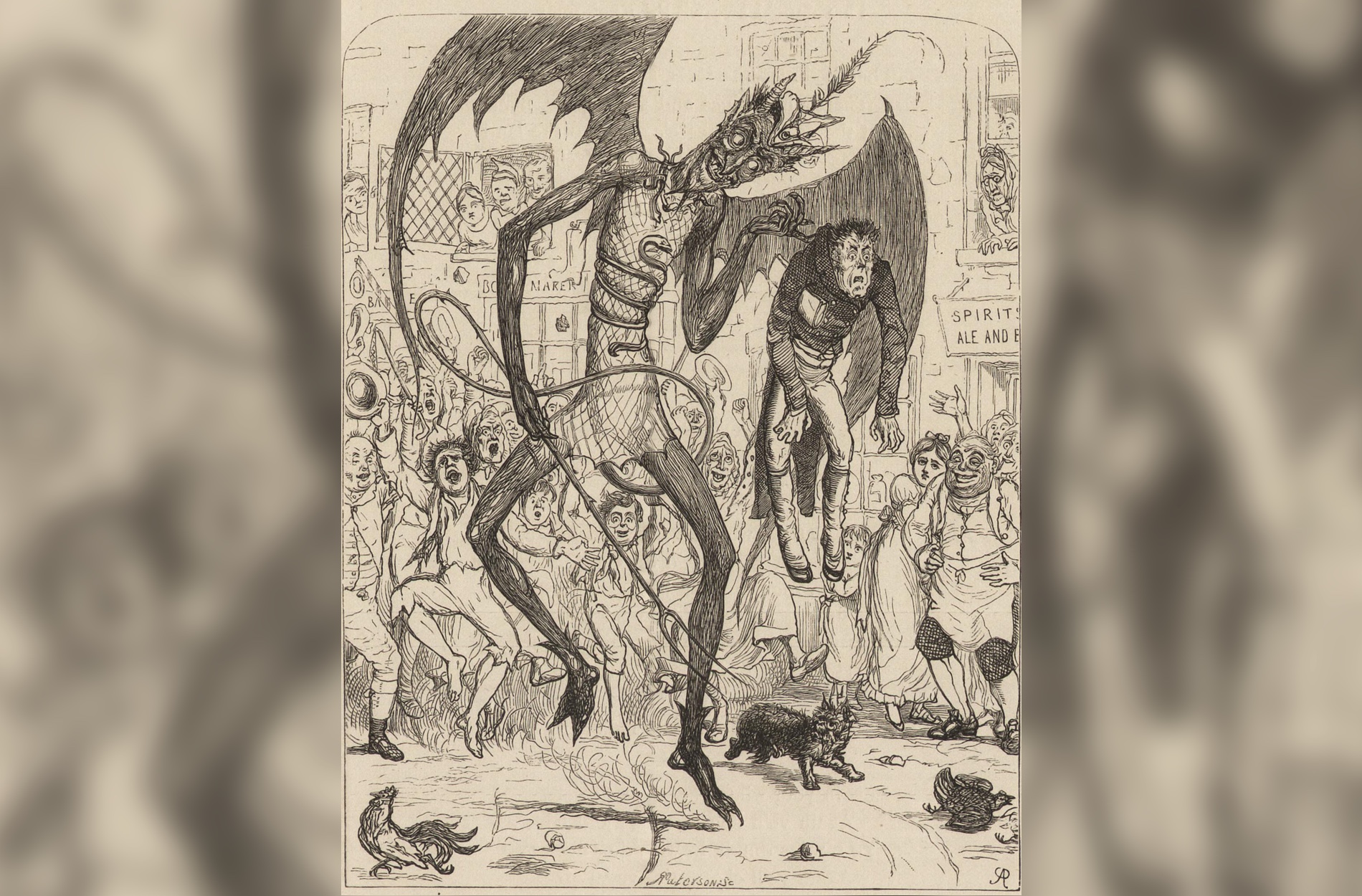

Government officers known as "excisemen" — tax enforcers — scoured the Scottish Highlands, confiscating illegal whisky and distilling equipment.

The excisemen enforced taxes and prevented smuggling; and they often became hated figures in Scottish society as a result.

Scotland's national poet Robert Burns, who worked as an exciseman himself, wrote a song suggesting many excisemen should go to hell: The Deil's Awa wi' th' Exciseman, or The Devil Has Taken the Exciseman.

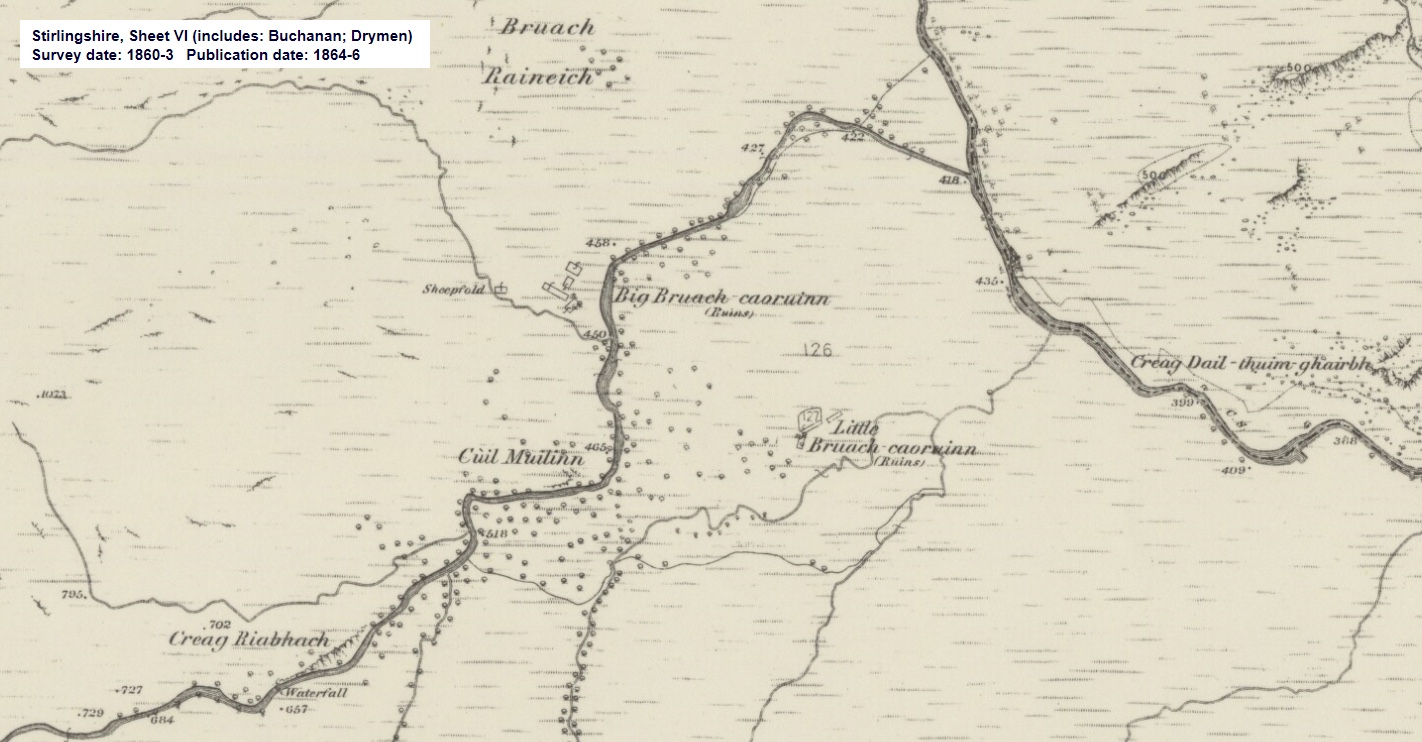

Historic map

The stone buildings hidden in the forest above Loch Ard were not completely unknown.

This map from the 1860s shows them as two groups of farm buildings, a few hundred feet from each other: Big Bruach Caoriunn and Little, or Wee, Bruach Caoriunn — the Scottish word bruach signifying a medieval landholding.

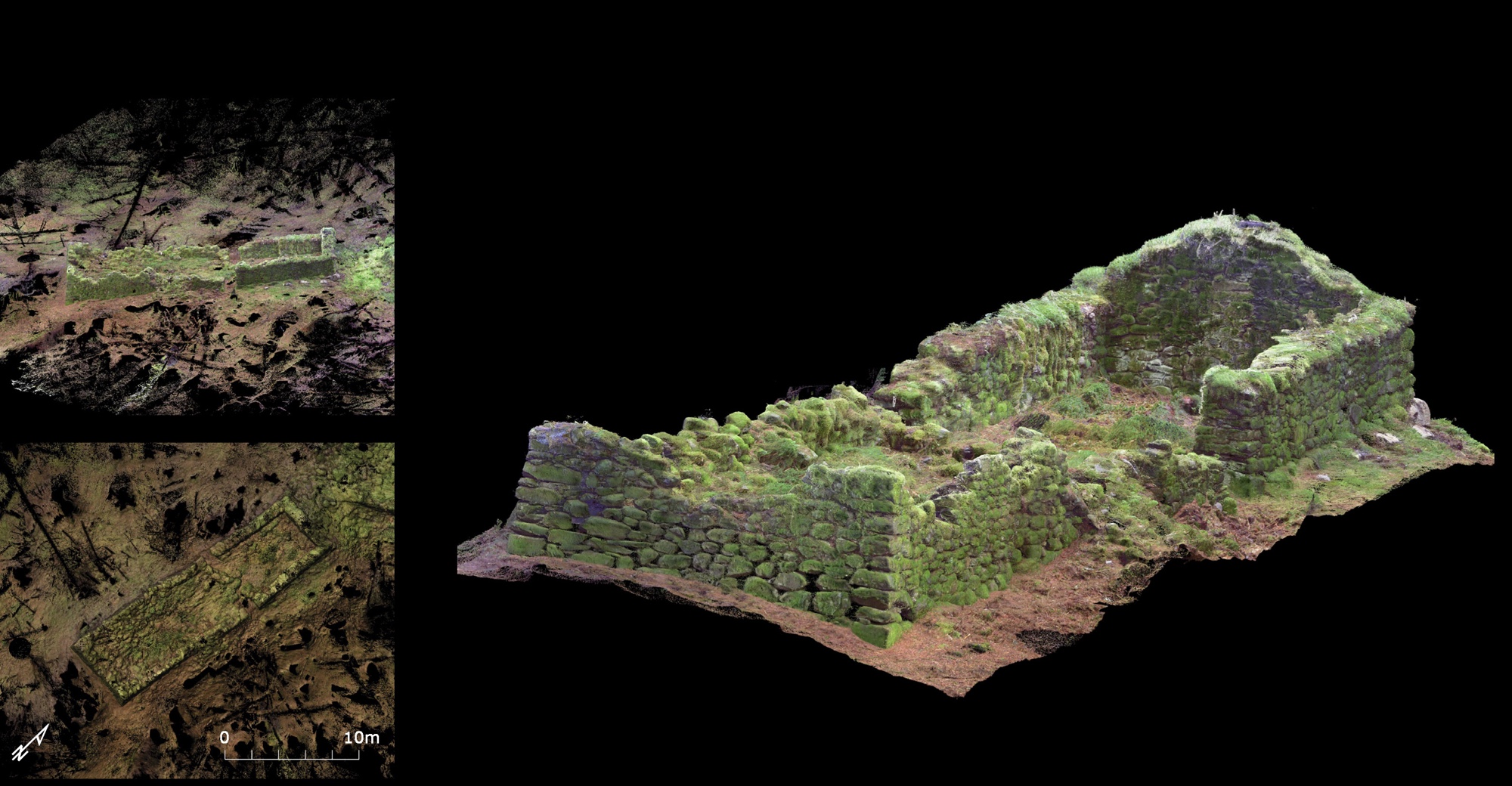

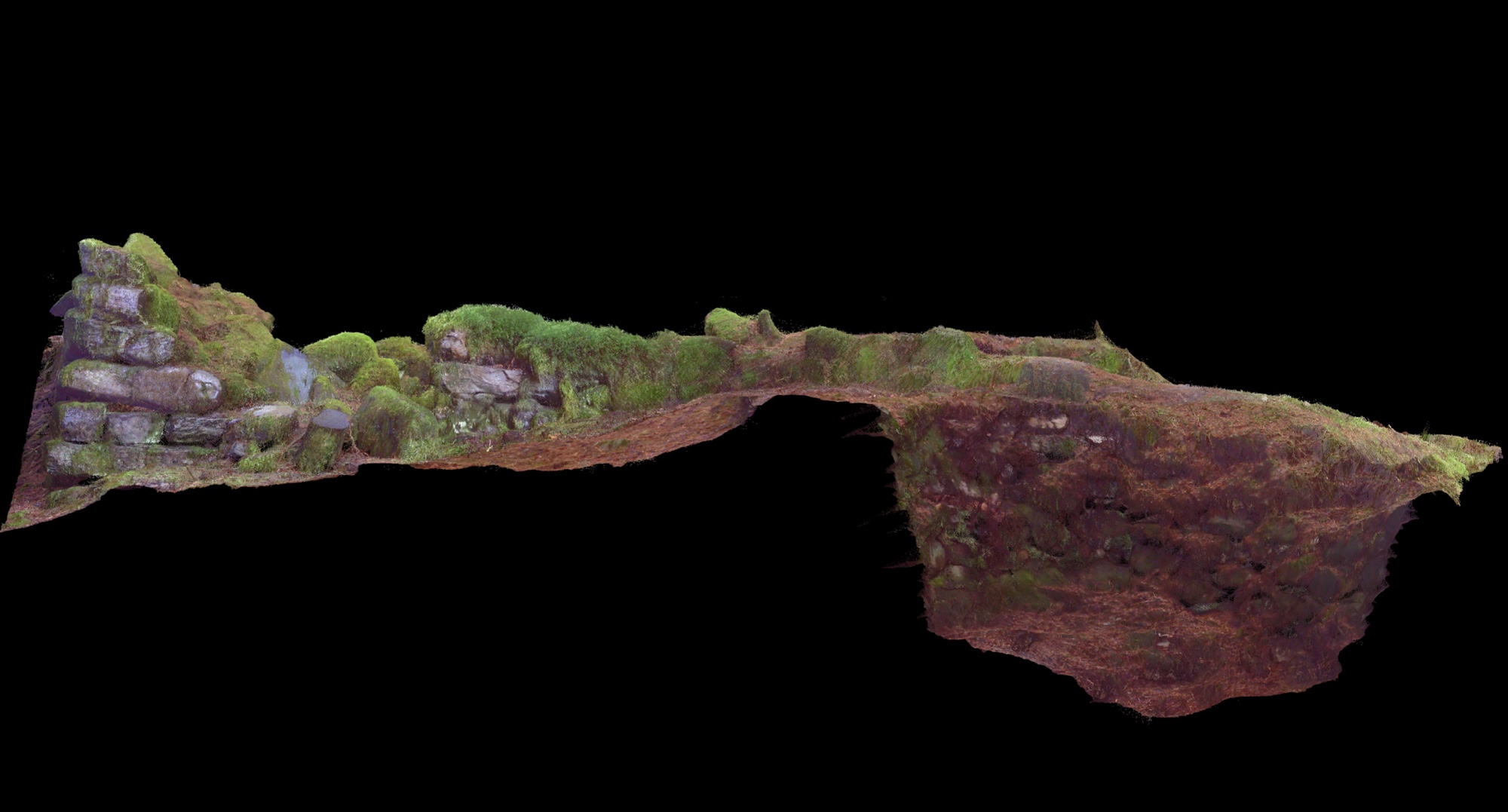

Stone ruins

Today, both groups of stone buildings are in ruins within the forest. Their roofs have now fallen in, but the stone walls are well preserved.

This is a review of the smaller of the two groups of buildings, the Wee Bruach, from the southwest.

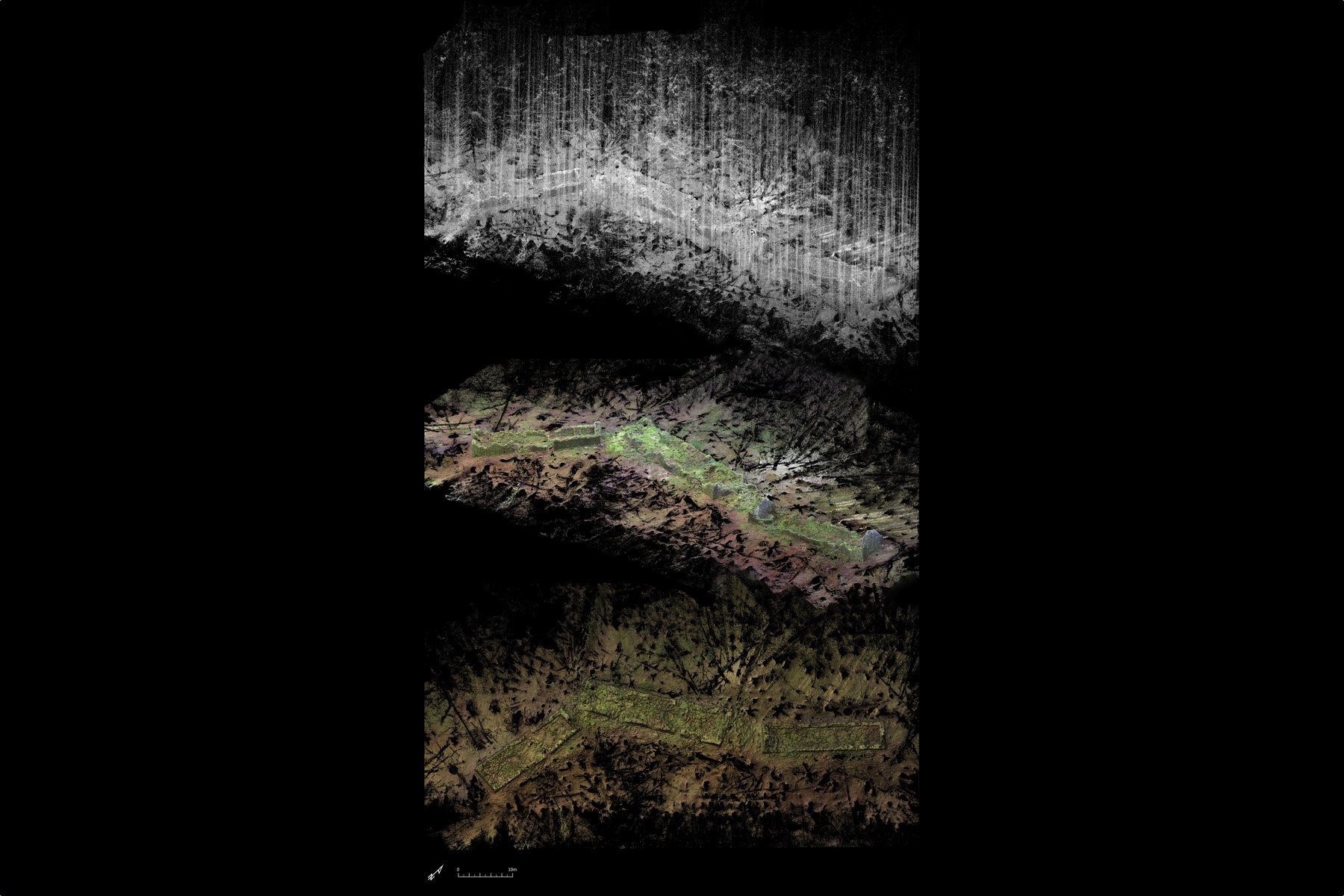

Forest setting

While carrying out the survey with digital laser scanners, archaeologists were careful to emphasize the forests of Douglas fir trees surrounding the ruined buildings — a dramatic feature of the site.

The three-dimensional laser scans of the buildings were combined with laser scans of the surrounding forest to give an overall picture of the site.

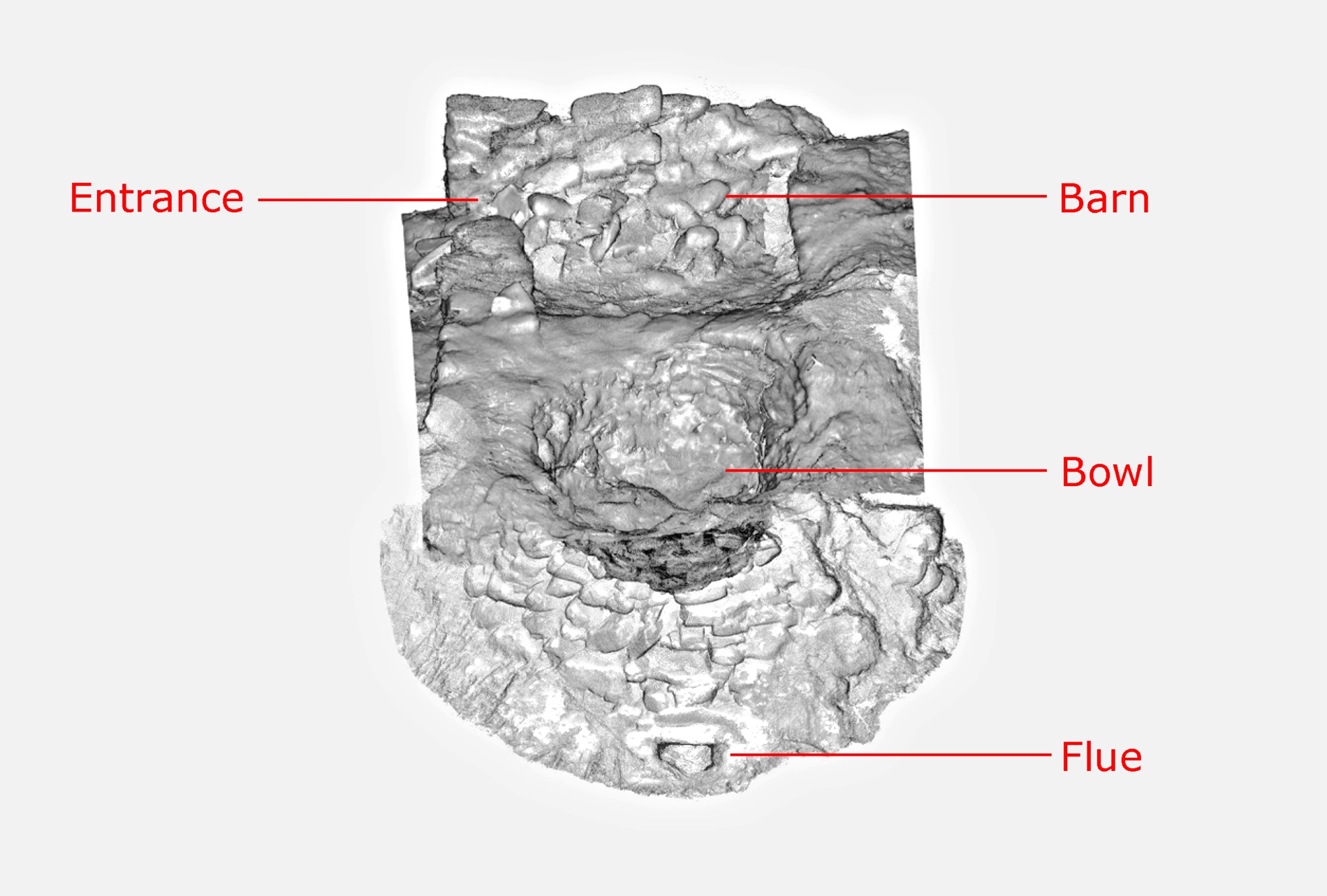

Ruined kilns

Of special interest are two large brick kilns at the site, one beside each group of farm buildings, that would have been used to dry farmed grains – or to malt barley by roasting it for the whisky-making process.

The front of the kiln of the Wee Bruach has collapsed, but its central chamber or bowl is intact; while the central bowl of the kiln at the Big Bruach has collapsed, but its front and flue are intact.

Grain-drying kiln

By combining the digital data from the laser scans of the two ruined kilns, archaeologists have been able to reconstruct how a complete kiln would have looked.

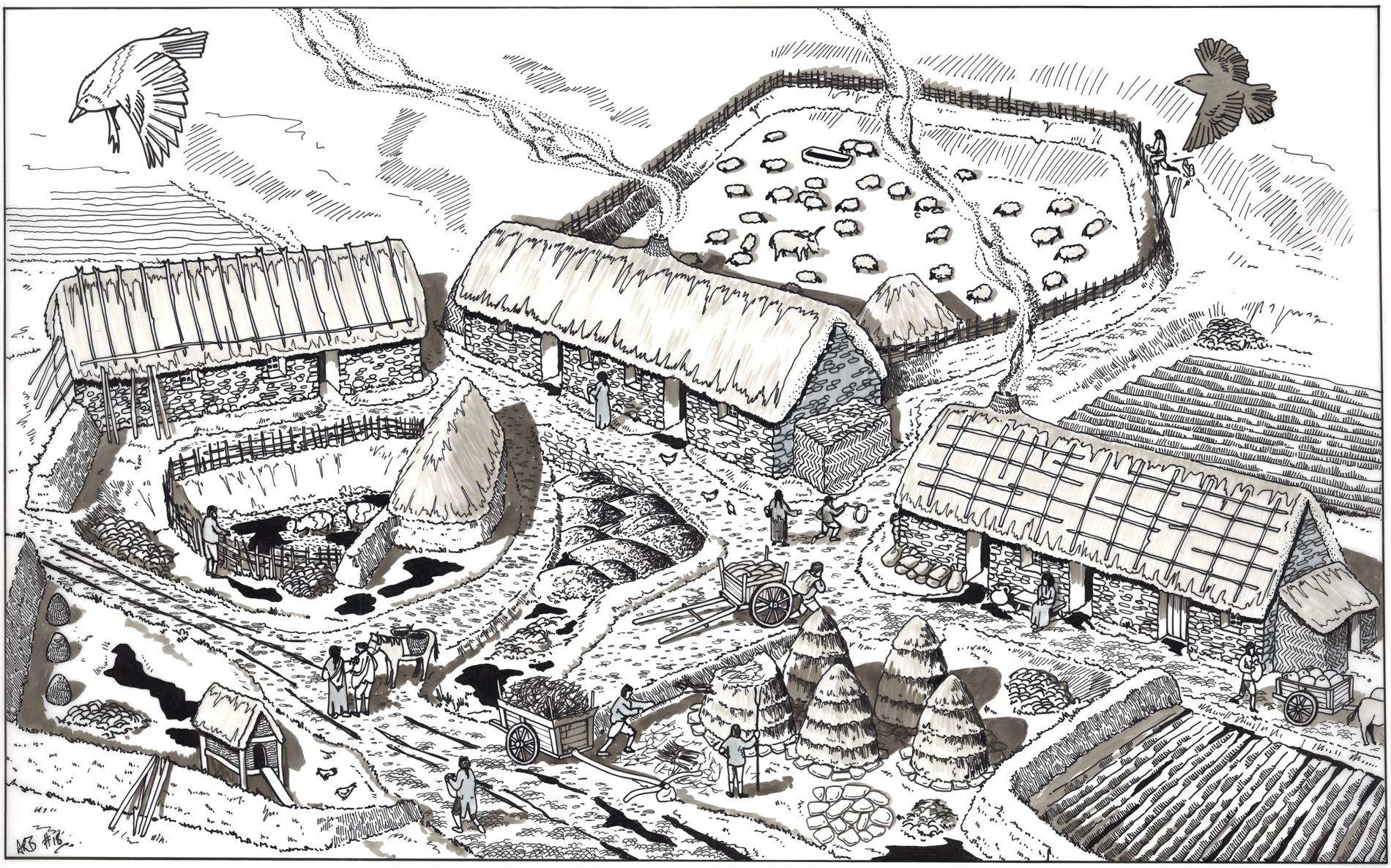

Artist's impression

The smaller of the two groups of ruined buildings — those of the Wee Bruach — are more complete.

Three-dimensional data from the laser scans of the buildings of the Wee Bruach have now been used to create an artist's impression of how it might have looked in the late 1700s and early 1800s.

Wee Bruach

The artist's interpretation shows the buildings of the Wee Bruach as a working sheep farm — a legitimate activity by all appearances.

But at the same time, it may have hidden its most profitable enterprise — illicit whisky distilling — from the government's excisemen.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.