Physicists want to use gravitational waves to 'see' the beginning of time

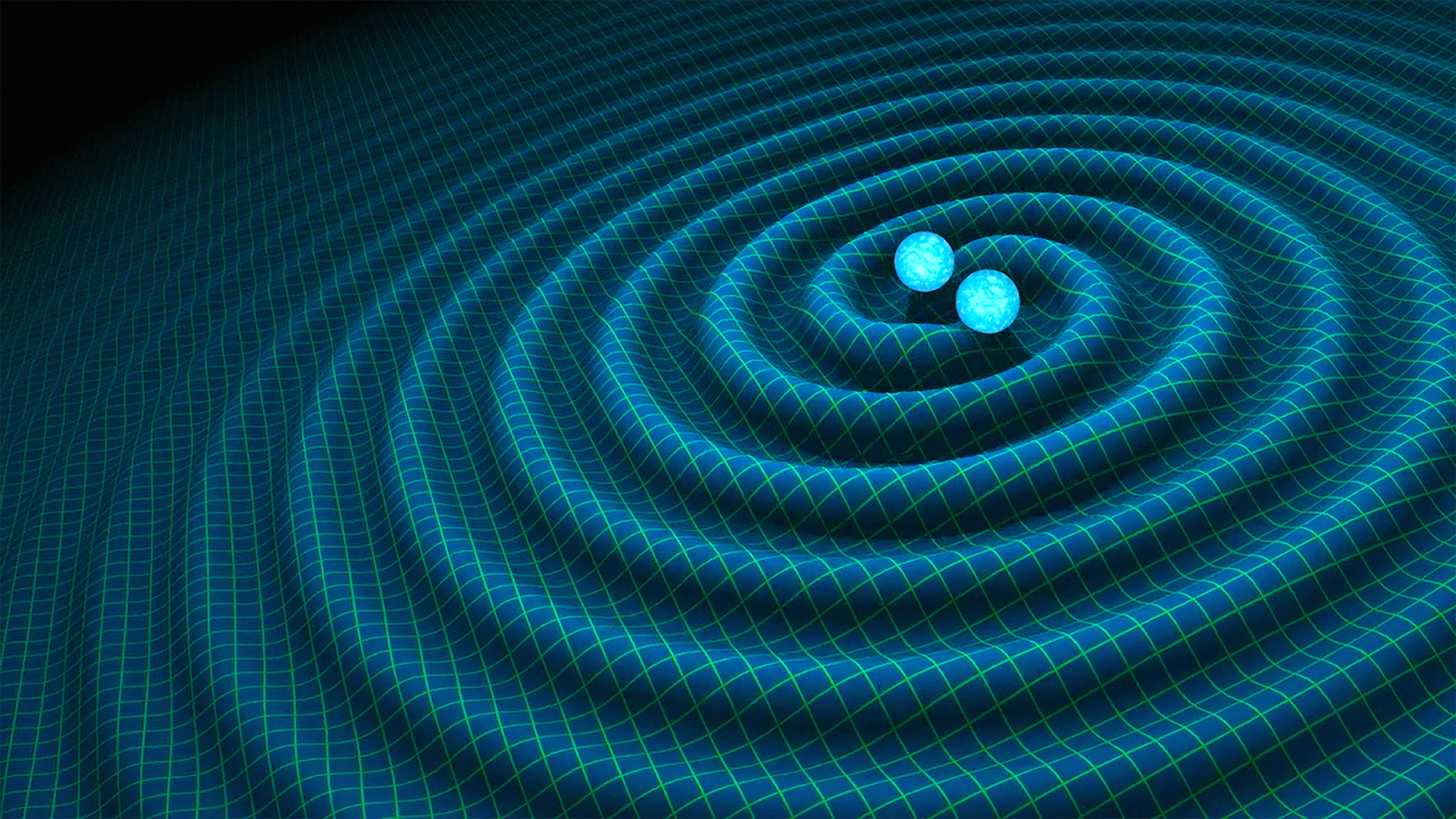

Gravitational waves are ripples in the fabric of space. Waves that originated in the early universe could carry important information about the phenomena that occurred there.

Ripples in space-time known as gravitational waves could help reveal the secrets at the dawn of time, just moments after the Big Bang, new research suggests. And physicists say they can learn more about these primeval gravitational waves using nuclear fusion reactors here on Earth.

In a new study, physicists used equations that govern how electromagnetic waves move through plasma inside fusion reactors to create a theoretical model for how gravitational waves and matter interact.

That, in turn, could reveal a better picture of the earliest moments in time.

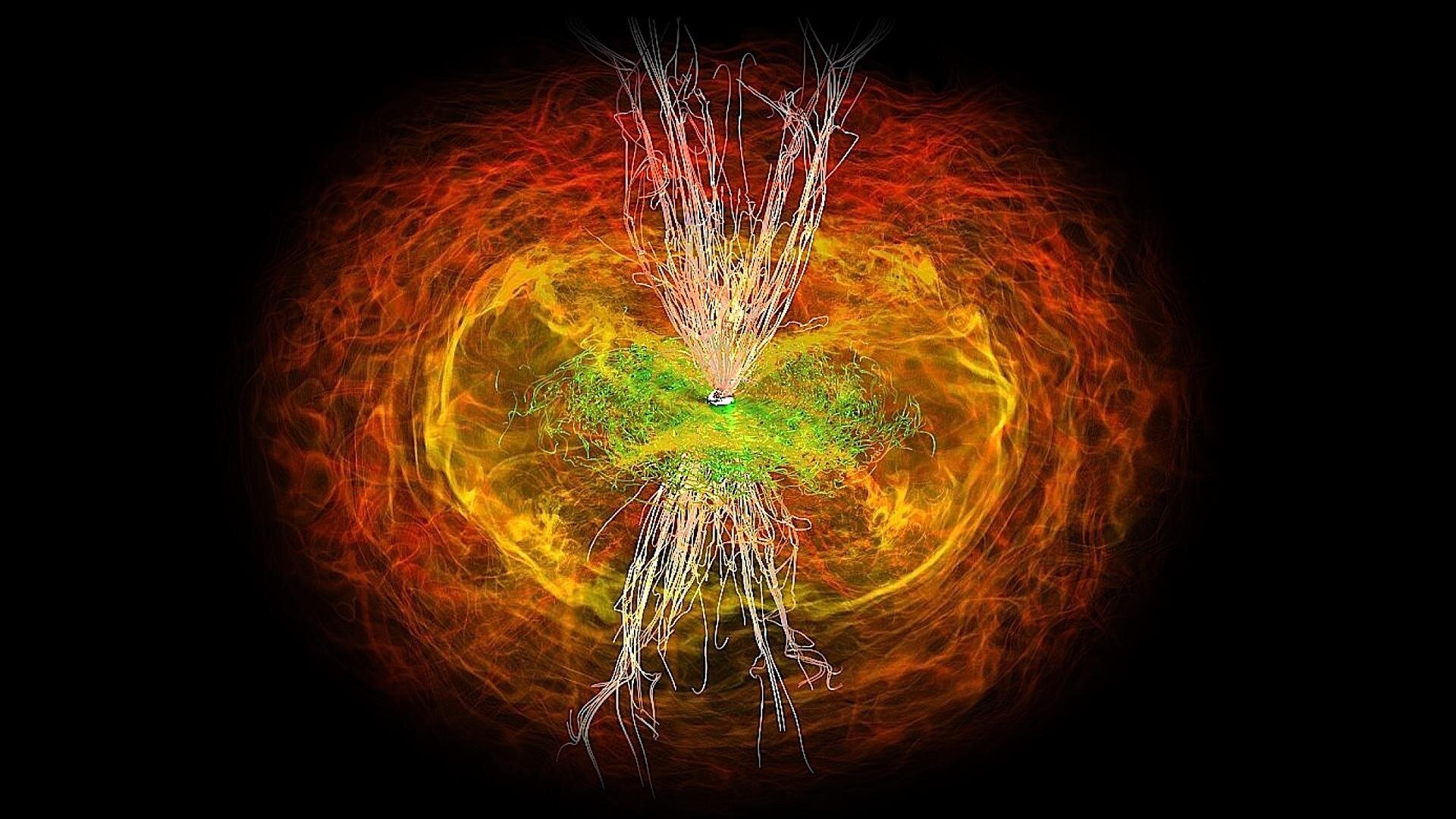

Moments after the Big Bang, the universe was permeated by a soup of hot, ultradense primordial plasma that sent powerful gravitational waves rippling out into the cosmos.

These ancient gravitational waves would have propagated throughout the universe and should still be present today, so the mutual influence that matter and gravitational waves had on each other in the universe's infancy would leave observable traces in both. Working backward from those observable traces could reveal a better picture of that early period.

"We can't see the early universe directly, but maybe we can see it indirectly if we look at how gravitational waves from that time have affected matter and radiation that we can observe today," said Deepen Garg, a graduate student in the Princeton Program in Plasma Physics and lead author of the study, in a statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A matter of great gravity

According to Einstein's theory of general relativity, massive bodies interact gravitationally by deforming space around them, generating ripples in space-time called gravitational waves that travel at the speed of light.

Until now, physicists have used detectors such as the Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory (LIGO) to hunt gravitational waves born in the collisions of black holes. These cosmic cataclysms generate the most powerful gravitational waves, and they travel from the collision region to Earth in a vacuum, meaning that to describe them, physicists need only model the physics of these ripples in empty space.

However, when the universe was in its infancy, huge amounts of matter moved around, generating gravitational waves that had to propagate through a primordial plasma, which would have interacted with the waves, altering their shape and trajectory.

To calculate how this primordial plasma would have affected these ancient gravitational waves, Garg and his supervisor Ilya Dodin carefully analyzed the equations of Einstein's theory of relativity, which describes how the geometry of space changes as matter moves through it. Under certain simplifying assumptions about the physical properties of matter, they could calculate how gravitational waves and matter affect each other.

The team based part of their equations on the propagation of electromagnetic waves in plasma. This process not only occurs under the surface of stars, but also in fusion reactors on Earth.

"We basically put plasma wave machinery to work on a gravitational wave problem," Garg said.

Although scientists have taken an important step toward computing the measurable effects that gravitational waves and primordial plasma may have had on each other, they still have a lot of work to do. The scientists still need to make more accurate and detailed calculations in order to get a better picture of what these ancient gravitational waves would look like today.

"We have some formulas now, but getting meaningful results will take more work," concluded Garg.

The findings were published in The Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics.

Andrey got his B.Sc. and M.Sc. degrees in elementary particle physics from Novosibirsk State University in Russia, and a Ph.D. in string theory from the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel. He works as a science writer, specializing in physics, space, and technology. His articles have been published in AdvancedScienceNews, PhysicsWorld, Science, and other outlets.