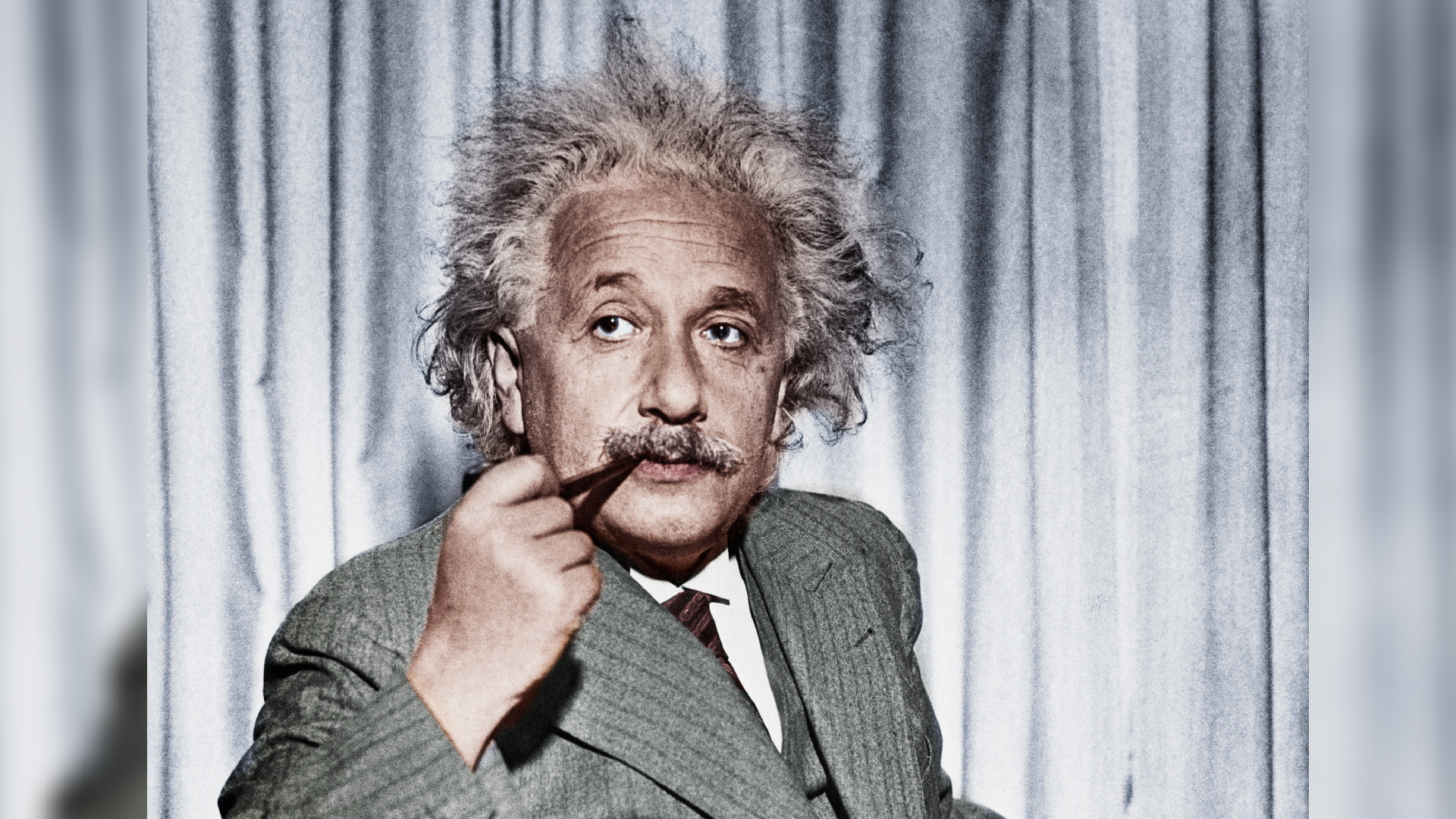

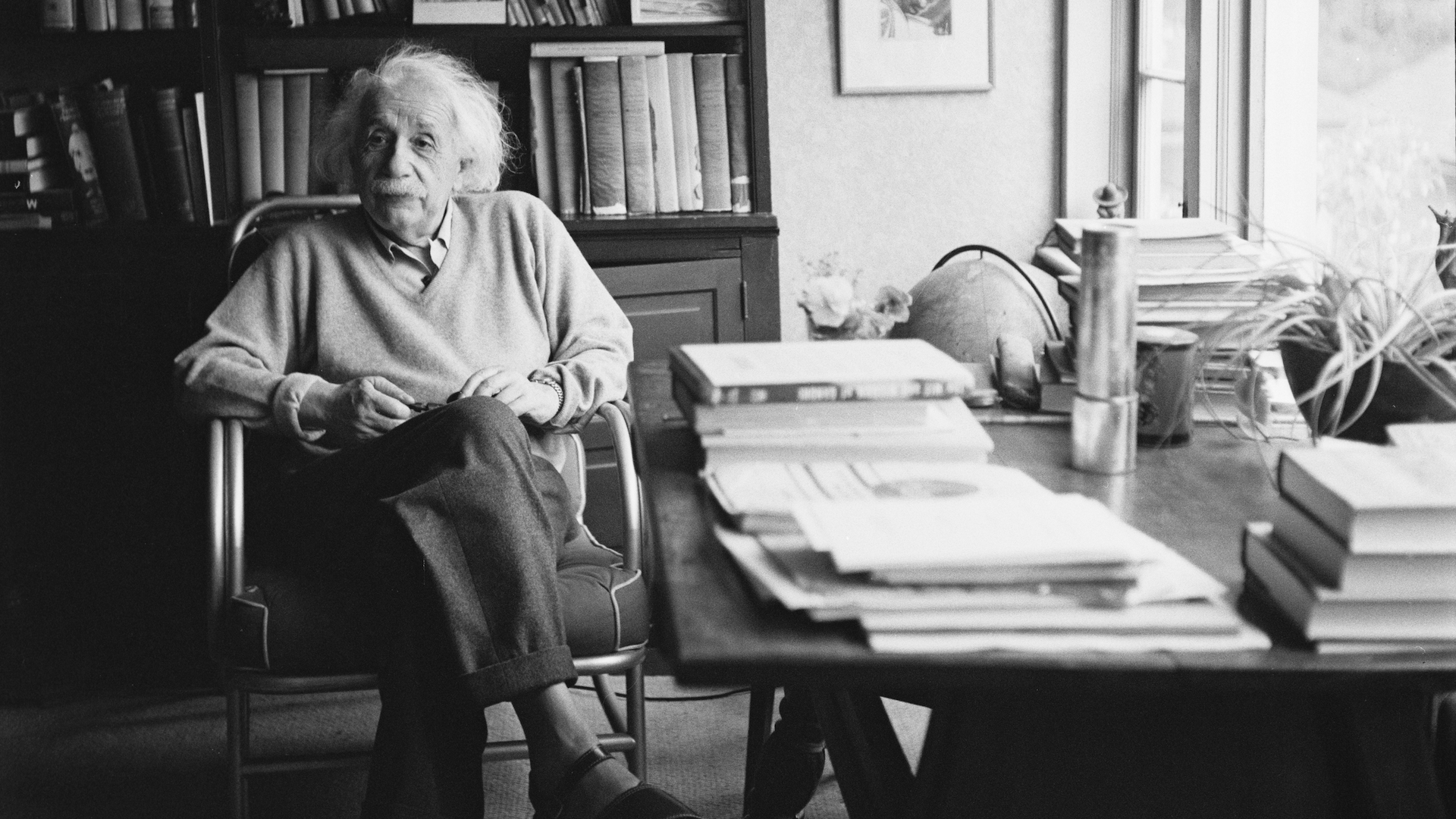

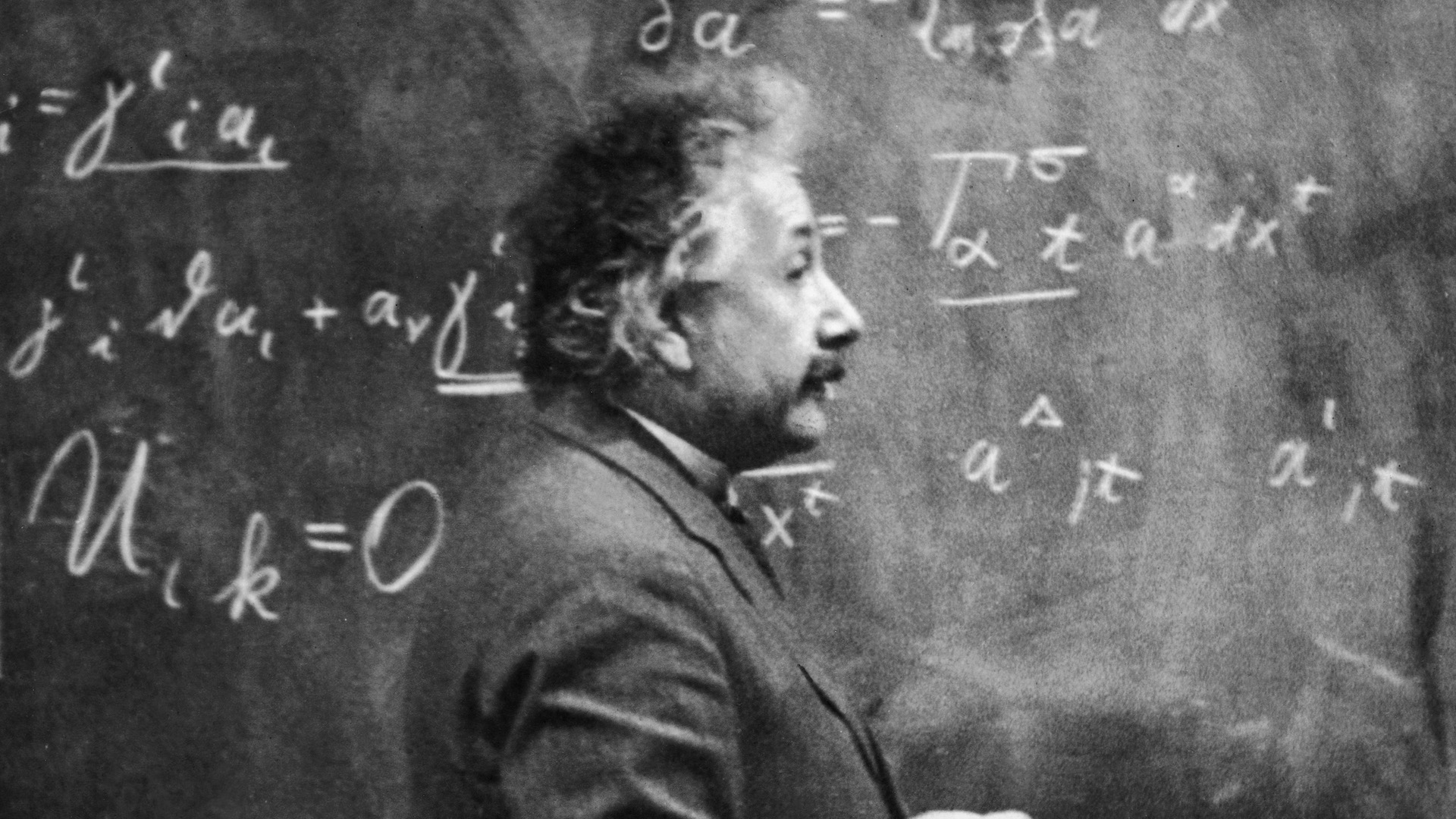

32 fun and random facts about Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein was much more than a scientific genius. From his political beliefs to his hatred of socks, here are 32 facts about Einstein you might not have heard before.

Albert Einstein was arguably the most famous scientist of the 20th century. Most people are familiar with his iconic E=mc^2 equation, but his life and work encompassed so much more than that. For instance, the brilliant physicist actually won the Nobel Prize for very different work. From his humble beginnings as a patent clerk to the offer to run a small country (that he turned down), here are 32 facts you may not have known about Einstein.

Einstein discovered that the universe has a "speed limit."

His special theory of relativity, which explains the relationship between mass, time and space, suggests that as an object approaches the speed of light, its mass and energy become infinite, as Space.com explains. That means that it's impossible for an object to travel faster than light.

He argued that space and time are interwoven.

While Einstein didn't invent the concept of space-time, which was first proposed by German mathematician Hermann Minkowski, his special theory of relativity showed that space and time grow and shrink relative to one another in order to keep the speed of light constant for the observer. Based on his theory, when we travel through space, time moves a tiny bit slower. At incredible speeds, like the speed of light, time stands still.

He won the Nobel Prize for his explanation of the photoelectric effect.

The photoelectric effect is the observation that metal plates eject electrons when hit by beams of high-energy light. The photoelectric effect can't be explained by classical physics, which saw light as a wave. Einstein proposed that we view light as both a particle and a wave — with the frequency of the wave determining the energy of the particle and vice versa.

Einstein transformed the way physicists view light.

Before Einstein's special theory of relativity, physicists thought that light traveled through a substance called "the luminiferous ether." Throughout the late 19th century, scientists ran experiments to try to prove its existence.

Einstein's fascination with physics was lifelong.

Beginning at age 5, Einstein became captivated by the invisible forces that moved the needle of his compass, according to the American Physical Society. That led to a lifelong quest to explain those invisible forces.

At the age of 12, he taught himself geometry.

To study, he read out of a textbook, which he dubbed his "holy geometry book" and "second miracle" (the first being his compass needle).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

He wasn't well-liked by his teachers.

One of the instructors at the Luitpold-Gymnasium in Munich, where Einstein received much of his early education, told the young Einstein that nothing good would ever come of his life.

Einstein played the violin.

At 5 years old, his mother signed him up for lessons. At first, he didn't enjoy playing at all, according to the American Nuclear Society. But after discovering Mozart, he developed a love for the hobby and played into his old age.

He wrote his first scientific paper at the age of 16.

Titled "On the Investigation of the State of the Ether in a Magnetic Field," the essay asked how magnetic fields impact "ether," the theoretical substance that at the time was believed to transmit electromagnetic waves.

After university, Einstein was rejected from every academic position he applied for.

Eventually, he settled for a job evaluating patent claims for the Swiss government, according to the American Institute of Physics. He described the job, which gave him the time and energy to focus on solving the physics problems that underlie our world, as "a kind of salvation."

He helped convince the physics world that atoms exist.

Einstein was interested in the problem of Brownian motion, the observation that if you put tiny objects (like pollen) in water, they appear to jump around erratically. Einstein proposed that invisible particles were colliding with the pollen, causing it to move, and came up with a formula describing this phenomenon. In 1908, French physicist Jean Baptiste Perrin tested and confirmed Einstein's theory, swaying the physics world to accept the existence of atoms, according to the American Physical Society.

Einstein was a pacifist.

At 16, he left Germany to escape mandatory military service. Later, he was one of only four German intellectuals to openly declare their opposition to German participation in World War I, calling nationalism "the measles of the human race."

Einstein's theories of relativity challenged the view that the universe was static.

His equations predicted a dynamic universe, one that was expanding or contracting. Flummoxed by this finding, Einstein assumed there was a flaw in his equations and introduced a "cosmological constant" which allowed for a universe that didn't change size. When Edwin Hubble confirmed that the universe is, indeed, expanding, Einstein called the cosmological constant "his greatest mistake."

Four of Einstein's most notable papers were all published in one year.

In 1905, dubbed his "year of miracles," Einstein published his explanation of the photoelectric effect, his theory on Brownian motion, and two papers on his general theory of relativity.

He was friends with Charlie Chaplin.

Chaplin even invited Einstein and his wife, Elsa Einstein, as his guests of honor at the premier of his 1931 film "City Lights." There, Chaplin famously told Einstein: "The people applaud me because everybody understands me, and they applaud you because no one understands you."

Einstein believed in God.

However, he didn't believe in a personal god that answered prayers. Instead, he thought that God revealed himself through the "harmony" of the universe. "He [God] does not play dice," he famously wrote.

Einstein was a target for the Nazis.

They sponsored conferences and book burnings against Einstein and labeled his theories "Jewish physics." In 1933, Einstein fled Germany to escape Nazi death threats, settling first in Britain and then eventually in Princeton, New Jersey.

His work enabled the development of the atomic bomb.

The equation E = mc2 provided the theoretical basis for the weapon's potential — but didn't explain how to build one.

At the start of World War II, he wrote to then-President Franklin D. Roosevelt, warning of possible German nuclear weapons research.

He urged the president to initiate development of an atomic bomb — but later regretted doing so, according to the American History of Natural History. In an interview with Newsweek, he said: "Had I known that the Germans would not succeed in developing an atomic bomb, I would have done nothing."

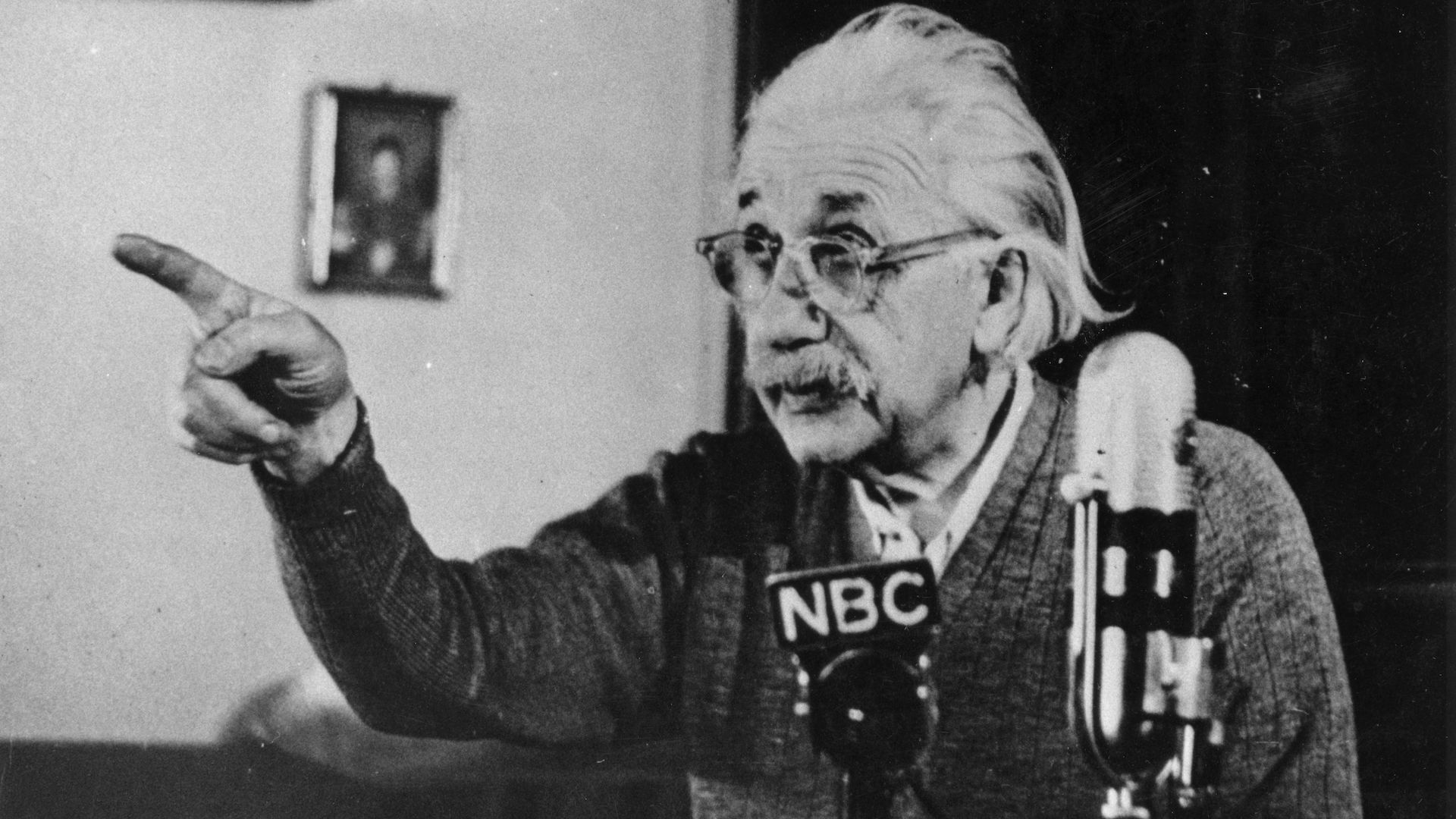

Later, he opposed the use of atomic weapons.

After the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, he formed the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists, an organization that educated Americans about the dangers of atomic weapons.

Einstein was a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

He saw parallels between the experience of Black Americans and his experience as a Jew living in Nazi Germany. In a 1946 commencement speech delivered at the historically black college Lincoln University, Einstein decried segregation and called it "a disease of white people," Smithsonian magazine reported.

The FBI kept a 1,400-page dossier on Einstein.

His pacifist stance and left-leaning politics made him suspicious in the eyes of the agency as a potentially "extreme radical," National Geographic reported. This was especially true during the McCarthy era, when many people were accused of communism or blacklisted from work.

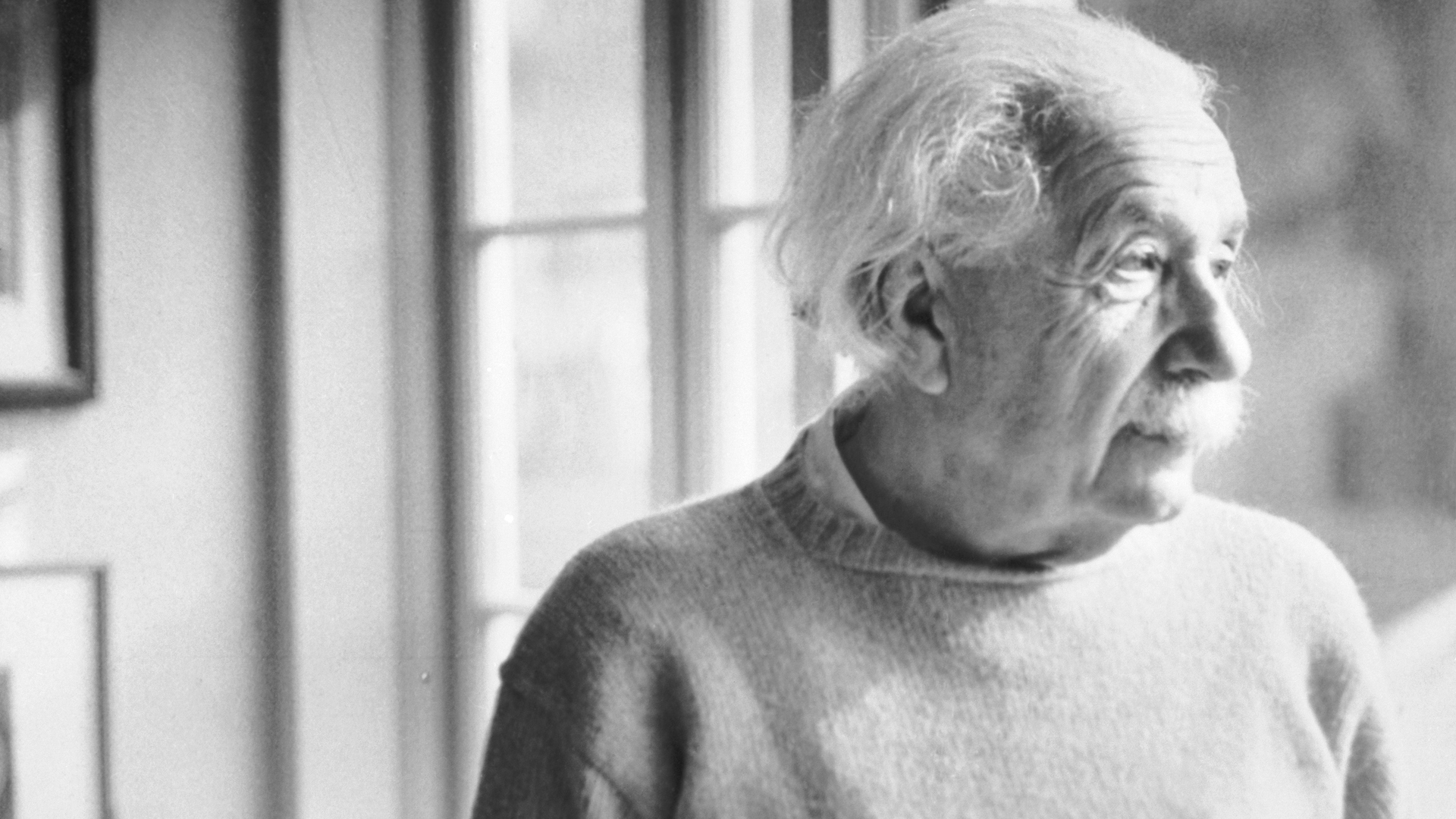

Einstein was asked to be the president of Israel.

However, when he was offered the position in 1952, he was already near the end of his life, according to the American Museum of Natural History. Due to his poor health and lack of experience "dealing properly with people," he declined.

He did not believe that black holes could exist.

In a 1939 article, he laid out a series of arguments trying to prove that black holes — objects with such high gravity that even light can't escape them — are impossible, Scientific American reported. Ironically, It's Einstein's general theory of relativity that shows us black holes do, in fact, exist.

He did believe in the possibility of wormholes.

In a 1935 paper published in the journal Physics Reviews, Einstein and physicist Nathan Rosen proposed that near objects of enormous mass, space-time might curve inward like a rubber tube, creating a tunnel between two different regions. If they exist, these objects would enable travel across vast distances of time and space, Space.com reported.

Einstein didn't wear socks.

Black holes weren't the only holes this physicist vehemently disagreed with. Because socks invariably develop holes, he disliked them to such an extent that he refused to wear them, according to the American Nuclear Society.

Einstein's brain was stolen.

After his death in 1955, pathologist Thomas Harvey dissected and stole Einstein's brain during an autopsy. Harvey, who wanted to discover the anatomical secrets of genius, eventually received permission from Einstein's son to use the brain for scientific research.

Research on Einstein's brain found extra folding.

The human brain's wrinkled surface gives it a much larger surface area than a smooth brain and is an important part of advanced cognition. Einstein's brain had extra folding in its gray matter, the site of conscious thinking, especially in the frontal lobe, where abstract thought and planning occurs.

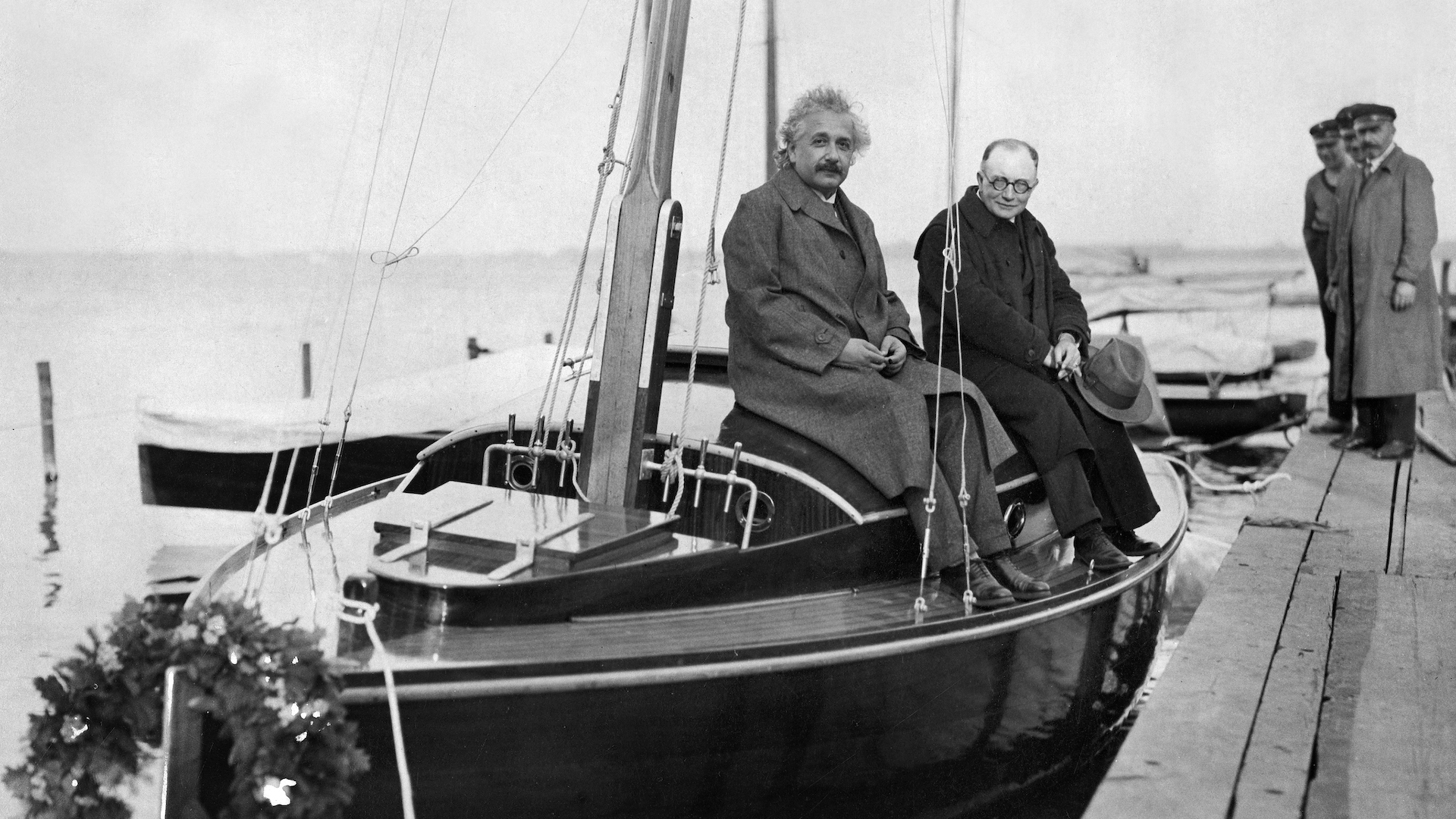

He loved sailing.

However, the physicist was terrible at it — so terrible, in fact, that his neighbors frequently had to rescue him when is boat invariably capsized, according to the American Nuclear Society.

His birthday is Pi Day.

March 14 is a special date because written numerically, it matches the first three digits of mathematical constant pi: 3.14. However, that's not the only reason it's significant. It's also the birthday of Einstein, who was born in 1879.

Einstein invented a refrigerator.

The contraption, which he developed alongside colleague Leo Szilard, didn't require motors or coolant. Instead, it used boiling butane to suck energy from a compartment, lowering the temperature inside, Live Science previously reported.

Einstein's ultimate goal was to describe the workings of the entire universe — from subatomic particles to the farthest reaches of space — in one theory.

He called the concept "The Grand Unified Theory." He never realized this dream, but physicists are still working to find it.

Quantum Drama: From the Bohr-Einstein Debate to the Riddle of Entanglement — available on Amazon

Although he may be the most famous, Albert Einstein wasn't the only great scientist of the early 20th century, and his interactions with Danish physicist Niels Bohr would become known as one of the most famous debates in the history of science.

Their subject was quantum physics, and the drama that unfolded between them is expertly captured in this book by Jim Baggott and the late science writer John Heilbron.

Isobel Whitcomb is a contributing writer for Live Science who covers the environment, animals and health. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Fatherly, Atlas Obscura, Hakai Magazine and Scholastic's Science World Magazine. Isobel's roots are in science. She studied biology at Scripps College in Claremont, California, while working in two different labs and completing a fellowship at Crater Lake National Park. She completed her master's degree in journalism at NYU's Science, Health, and Environmental Reporting Program. She currently lives in Portland, Oregon.