32 physics experiments that changed the world

From the discovery of gravity to the first mission to defend Earth from an asteroid, here are the most important physics experiments that changed the world.

Physics experiments have changed the world irrevocably, altering our reality and enabling us to take gigantic leaps in technology. From ancient times to now, here's a look at some of the greatest physics experiments of all time.

Conservation of energy

Energy conservation — the idea that energy cannot be created or destroyed, only transformed — is one of the most important laws of physics. James Prescott Joule demonstrated this rule, the first law of thermodynamics, when he filled a large container with water and fixed a paddle wheel inside it. The wheel was held in place by an axle with a string around it and then looped over a pulley and attached to a weight, which, when dropped, caused the wheel to spin. By sloshing the water with the wheel, Joule demonstrated that the heat energy gained by the water from the wheel's movement was equal to the potential energy lost by dropping the weight.

Measurement of the electron's charge

As the fundamental carriers of electric charge, electrons carry the smallest amount of electricity possible. But the particles are truly tiny, with a mass 1,838 times smaller than the already-minuscule proton.

So how could you measure the charge on something so small? Physicist Robert Millikan's answer was to drop electrically charged oil drops through the plates of a capacitor and adjust the voltage of the capacitor until the electric field it emitted produced a force on some of the drops that balanced out gravity — thus suspending them in the air. Repeating the experiment for different voltages revealed that, no matter the size of the drops, the total charge it carried was a multiple of a base number. Millikan had found the fundamental charge of the electron.

"Gold foil experiment" revealing the structure of the atom

Once thought to be indivisible, the atom was slowly divided and split by a series of experiments during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These included J.J. Thomson's 1897 discovery of the electron and James Chadwick's 1932 identification of the neutron. But perhaps the most famous of these experiments was Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden's "gold foil experiment." Under the direction of Ernest Rutherford, the students fired positively charged alpha particles at a thin sheet of gold foil. To their surprise, the particles passed through, revealing that atoms consisted of a positively charged nucleus separated by a significant empty space by their orbiting electrons.

Nuclear chain reaction

By the mid-20th century, scientists were aware of the basic structure of the atom and that, according to Einstein, matter and energy were different forms of the same thing. This set the stage for the wartime work of Enrico Fermi, who in 1942 demonstrated that atoms could be split to release enormous quantities of energy.

While working at the University of Chicago with an experimental setup he called an "atomic pile," Fermi demonstrated the first-ever controlled nuclear fission reaction. Fermi fired neutrons at the unstable isotope uranium-235, causing it to split and release more neutrons in a growing chain reaction. The experiment paved the way for the development of nuclear reactors and was used by J. Robert Oppenheimer and the Manhattan Project to build the first atomic bombs.

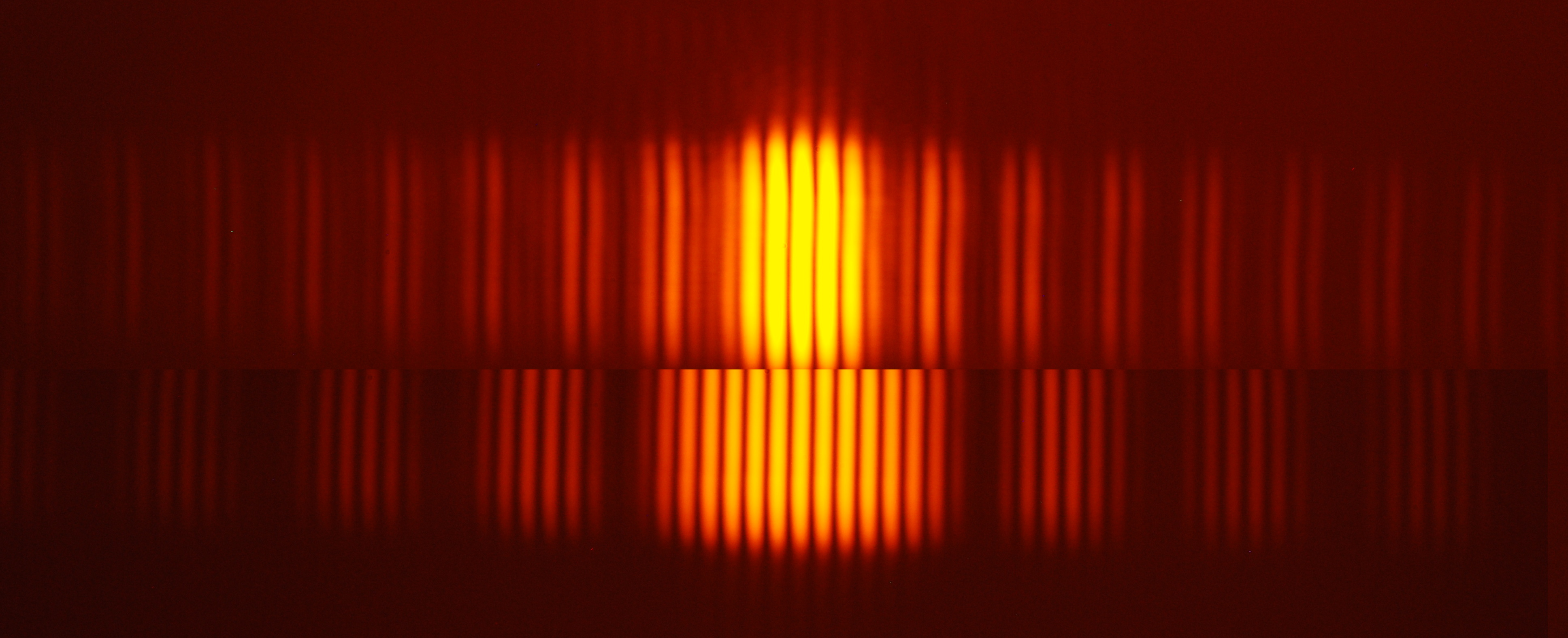

Wave-particle duality

One of the most famous experiments in physics is also one that illustrates, with disturbing simplicity, the bizarreness of the quantum world. The experiment consisted of two slits, through which electrons would travel to create an interference pattern on a screen, like waves. Scientists were stunned when they placed a detector near the screen and found that its presence caused the electrons to switch their behavior to act instead as particles.

First performed by Thomas Young to demonstrate the wave nature of light, the experiment was later used by physicists in the 20th century to show that all particles, including photons, were both waves and particles at the same time — and they acted more like particles when they were being measured directly.

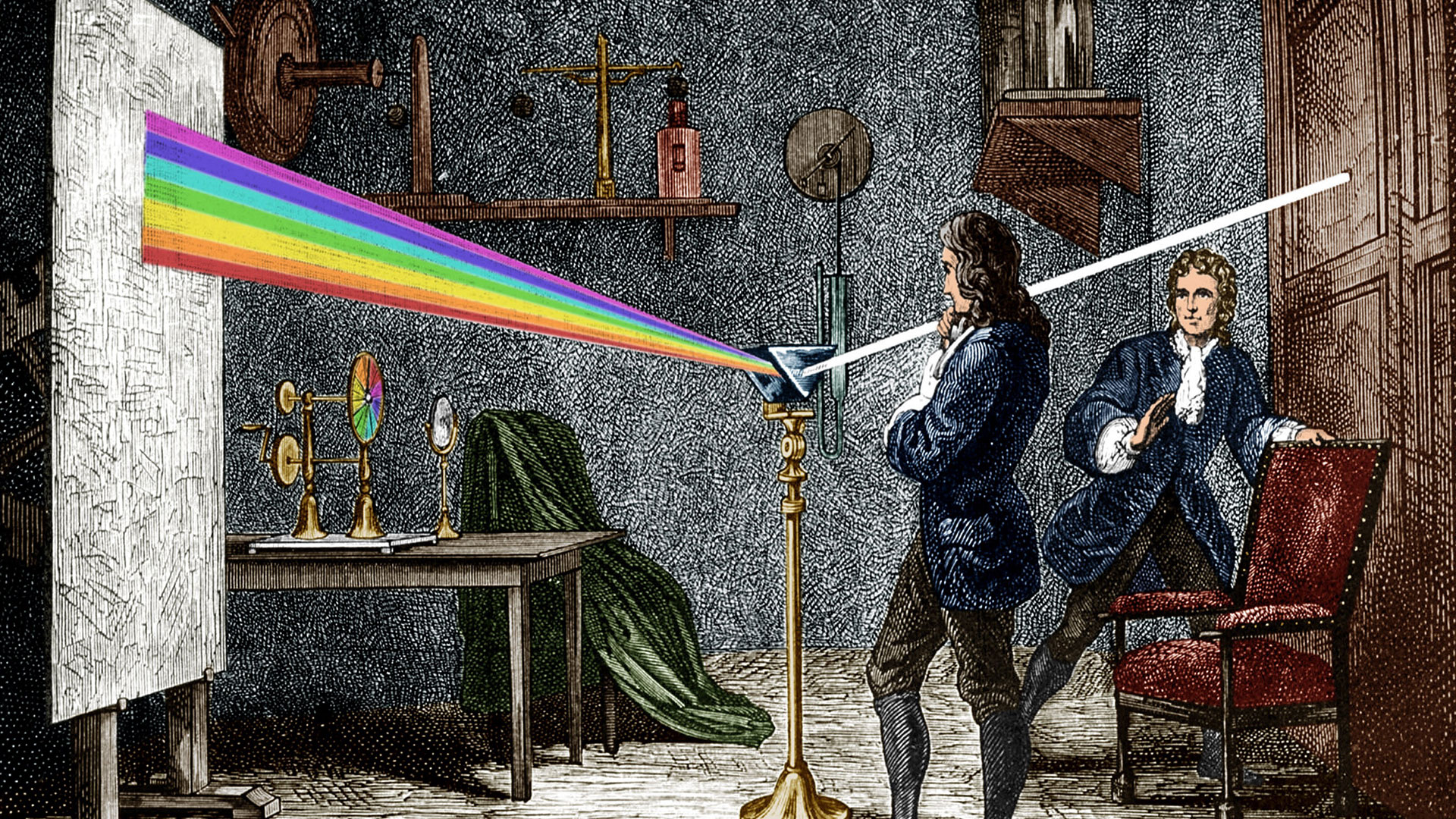

Splitting of white light into colors

White light is a mixture of all the colors of the rainbow, but before 1672, the composite nature of light was completely unknown. Isaac Newton determined this by using a prism that bent light of different wavelengths, or colors, by different amounts, decomposing white light into its composite colors. The result was one of the most famous experiments in scientific history and a discovery that, alongside other contributions by Newton, gave birth to the modern field of optics.

Discovery of gravity

In perhaps the most widely repeated story in all of science, Newton is said to have chanced upon the theory of gravity while contemplating under the shade of an apple tree. According to the legend, when an apple fell and struck him on the head, he supposedly yelled "Eureka!" as he realized that the same force that brought the apple tumbling to Earth also kept the moon in orbit around our planet and Earth circling the sun. That force, of course, would become known as gravity.

The story is slightly embellished, however. According to Newton's own account, the apple did not strike him on the head, and there's no record of what he said or if he said anything, at the moment of discovery. Nonetheless, the realization led Newton to develop his theory of gravity in 1687, which was updated by Einstein's theory of general relativity 228 years later.

Blackbody radiation

By the turn of the 20th century, many physicists — having advanced theories that explained gravity, mechanics, thermodynamics and the behavior of electromagnetic fields — were confident that they had conquered the vast majority of their field. But one troubling source of doubt remained: Theories predicted the existence of a "blackbody" — an object capable of absorbing and then remitting all incident radiation. The problem was that physicists couldn't find it.

In fact, data from experiments conducted with close approximations of black bodies — a box with a single hole whose inside walls are black — revealed that significantly less energy was emitted from blackbodies than classical theories led scientists to believe, especially at shorter wavelengths. The contradiction between experiment and theory became known as the "ultraviolet catastrophe."

The discovery prompted Max Planck to propose that the energy emitted by blackbodies wasn't continuous but rather split into discrete integer chunks called quanta. His radical proposal catalyzed the development of quantum mechanics, whose bizarre rules are completely unintuitive to observers living in the macroscopic world.

Einstein and the eclipse

Following its publication in 1915, Einstein's groundbreaking theory of general relativity briefly remained just that — a theory. Then, in 1919, astronomer Sir Arthur Eddington devised and completed stunning proof using that year's total solar eclipse.

Key to Einstein's theory was the notion that space — and, therefore, the path that light would follow through it — was warped by powerful gravitational forces. So, as the moon's shadow passed in front of the sun, Eddington recorded the position of nearby stars from his vantage point on the island of Principe in the Gulf of Guinea. By comparing these positions to those he had recorded at night without the sun in the sky, Eddington observed that they had been shifted slightly by the sun's gravity, completing his stunning proof of Einstein's theory.

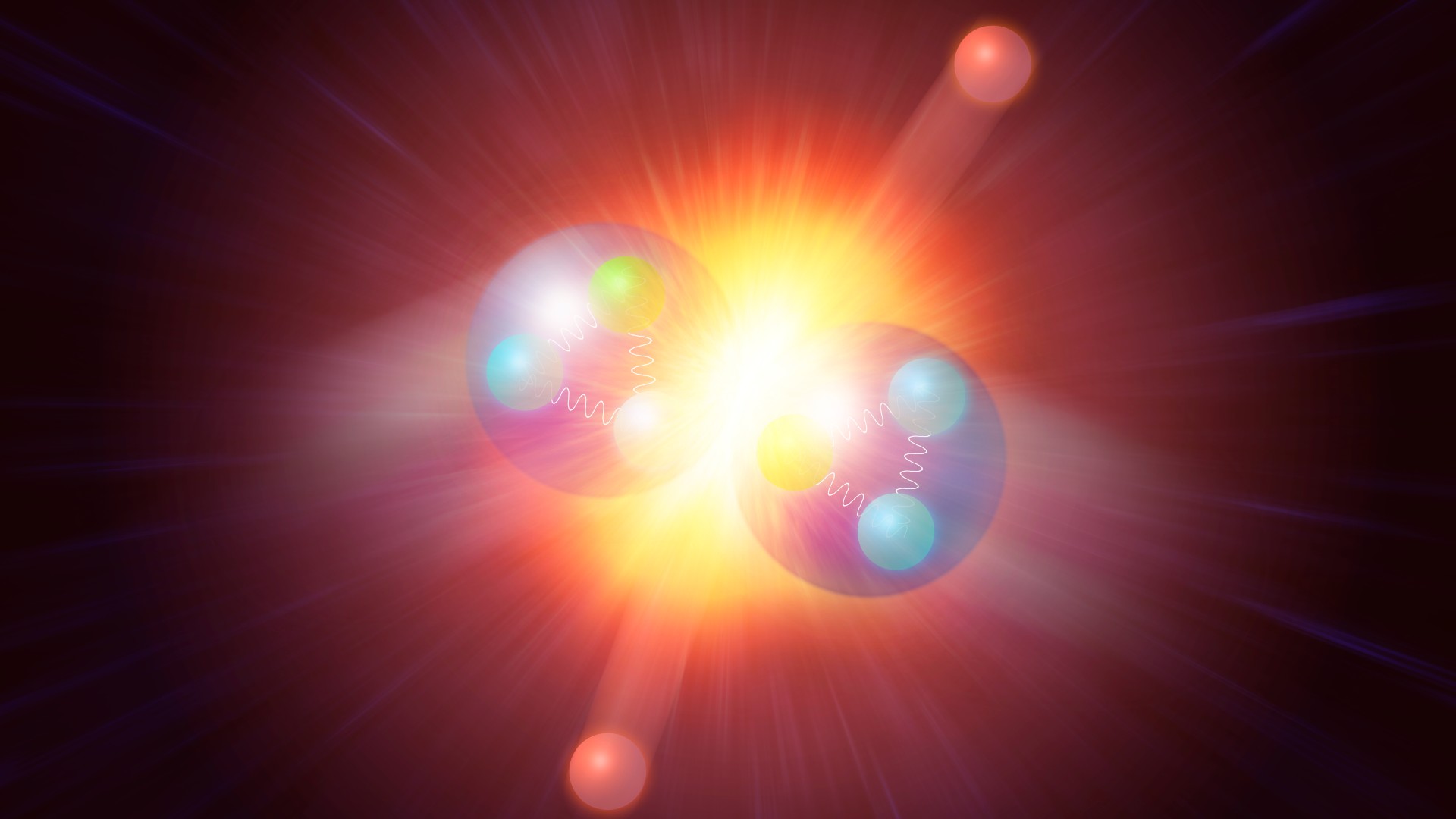

Higgs boson

In 1964, Peter Higgs suggested that matter gets its mass from a field that permeates all of space, imparting particles with mass through their interactions with a particle known as the Higgs boson.

To search for the boson, thousands of particle physicists planned, constructed and fired up the Large Hadron Collider. In 2012, after trillions upon trillions of collisions in which two protons are smashed together at near light speed, the physicists finally spotted the telltale signature of the boson.

Weighing the world

Although he's perhaps best known for his discovery of hydrogen, 18th-century physicist Henry Cavendish's most ingenious experiment accurately estimated the weight of our entire planet. Using a special piece of equipment known as a torsion balance (two rods with one smaller and one larger pair of lead balls attached to the end), Cavendish measured the minuscule force of gravitational attraction between the masses. Then, by measuring the weight of one of the small balls, he measured the gravitational force between it and Earth, giving him an easy formula for calculating our planet's density and — therefore, its weight — that remains accurate to this day.

Conservation of mass

Much like energy, matter in our universe is finite and cannot be created or destroyed, only rearranged. In 1789, to arrive at this startling conclusion, French chemist Antoine Lavoisier placed a burning candle inside a sealed glass jar. After the candle had burned and melted into a puddle of wax, Lavoisier weighed the jar and its contents, finding that it had not changed

Leaning Tower of Pisa experiment

Greek philosopher Aristotle believed that objects fall at different rates because the force acting upon them was stronger for heavier objects — a claim that went unchallenged for more than a millennium.

Then came the Italian polymath Galileo Galilei, who corrected Aristotle's false claim by showing that two objects with different masses fall at exactly the same rate. Some claim Galileo's famous experiment was conducted by dropping two spheres from the Leaning Tower of Pisa, but others say this part of the story is apocryphal. Nonetheless, the experiment was perhaps most famously demonstrated by Apollo 15 astronaut David Scott, who, while dropping a feather and a hammer on the moon, showed that without air, the two objects fell at the same speed.

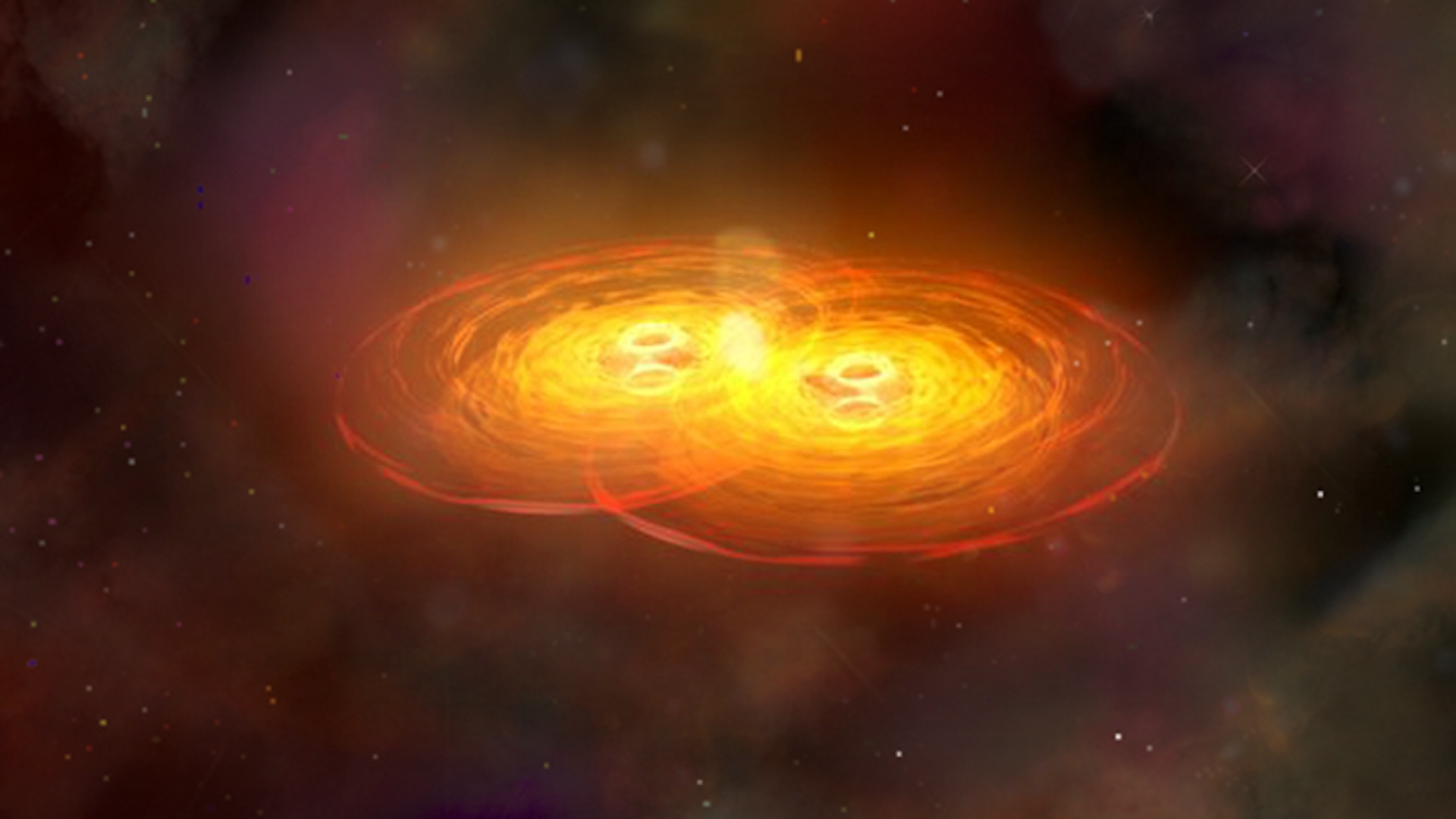

Detection of gravitational waves

If gravity warps space-time as Einstein predicted, then the collision of two extremely dense objects, such as neutron stars or black holes, should also create detectable shock waves in space that could reveal physics unseen by light. The problem is that these gravitational waves are tiny, often the size of a few thousandths of a proton or neutron, so detecting them requires an extremely sensitive experiment.

Enter LIGO, the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory. The L-shaped detector has two 2.5-mile-long (4 km) arms containing two identical laser beams. When a gravitational wave laps at our cosmic shores, the laser in one arm is compressed and the other expands, alerting scientists to the wave's presence. In 2015, LIGO achieved its task, making the first-ever direct detection of gravitational waves and opening up an entirely new window to the cosmos.

Destruction of heliocentrism

The idea that Earth orbits the sun goes back to the fifth century B.C. to Greek philosophers Hicetas and Philolaus. Nonetheless, Claudius Ptolemy's belief that Earth was the center of the universe later took root and dominated scientific thought for more than a millennium.

Then came Nicolaus Copernicus, who proposed that Earth did, in fact, revolve around the sun and not the other way around. Concrete evidence for this was later offered by Galileo, who in 1610 peered through his telescope to observe the planet Venus moving through distinct phases — proof that it, too, orbited the sun. Galileo's discovery did not win him any friends with the Catholic Church, which tried him for heresy for his unorthodox proposal.

Foucault's pendulum

First used by French physicist Jean Bernard Léon Foucault in 1851, the famous pendulum consisted of a brass bob containing sand and suspended by a cable from the ceiling. As it swung back and forth, the angle of the line traced out by the sand changed subtly over time — clear evidence that some unknown rotation was causing it to shift. This rotation was the spinning of Earth on its axis.

Discovery of the electron

In the 19th century, physicists found that by creating a vacuum inside a glass tube and sending electricity through it, they could make the tube give off a fluorescent glow. But exactly what caused this effect, called a cathode ray, was unclear.

Then, in 1897, physicist J.J. Thomson discovered that by applying a magnetic field to the rays inside the tube, he could control the direction in which they traveled. This revelation showed Thomson that the charge within the tube came from tiny particles 1,000 times smaller than hydrogen atoms. The tiny electron had finally been found.

Deflection of an asteroid

In 2022, NASA scientists hit an astronomical "bull's-eye" by intentionally steering the 1,210-pound (550 kilograms), $314 million Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) spacecraft into the asteroid Dimorphos just 56 feet (17 meters) from its center. The test was designed to see if a small spacecraft propelled along a planned trajectory could, if given enough lead time, redirect an asteroid from a potentially catastrophic impact with Earth.

DART was a smashing success. The probe's original goal was to change the orbit of Dimorphos around its larger partner — the 2,560-foot-wide (780 m) asteroid Didymos — by at least 73 seconds, but the spacecraft actually altered Dimorphos' orbit by a stunning 32 minutes. NASA hailed the collision as a watershed moment for planetary defense, marking the first time that humans proved capable of diverting Armageddon, and without any assistance from Bruce Willis.

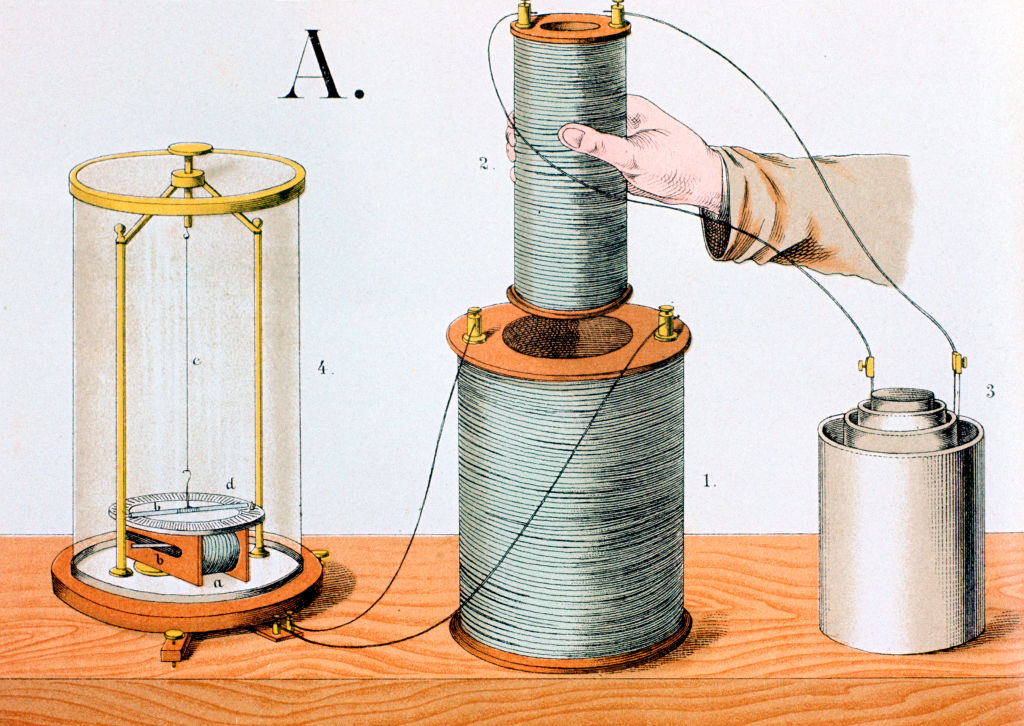

Faraday induction

In 1831, Michael Faraday, the self-taught son of a blacksmith born in rural south England, proposed the law of electromagnetic induction. The law was the result of three experiments by Faraday, the most notable of which involved the movement of a magnet inside a coil made by wrapping a wire around a paper cylinder. As the magnet moved inside the cylinder, it induced an electric current through the coil — proving that electric and magnetic fields were inextricably linked and paving the way for electric generators and devices.

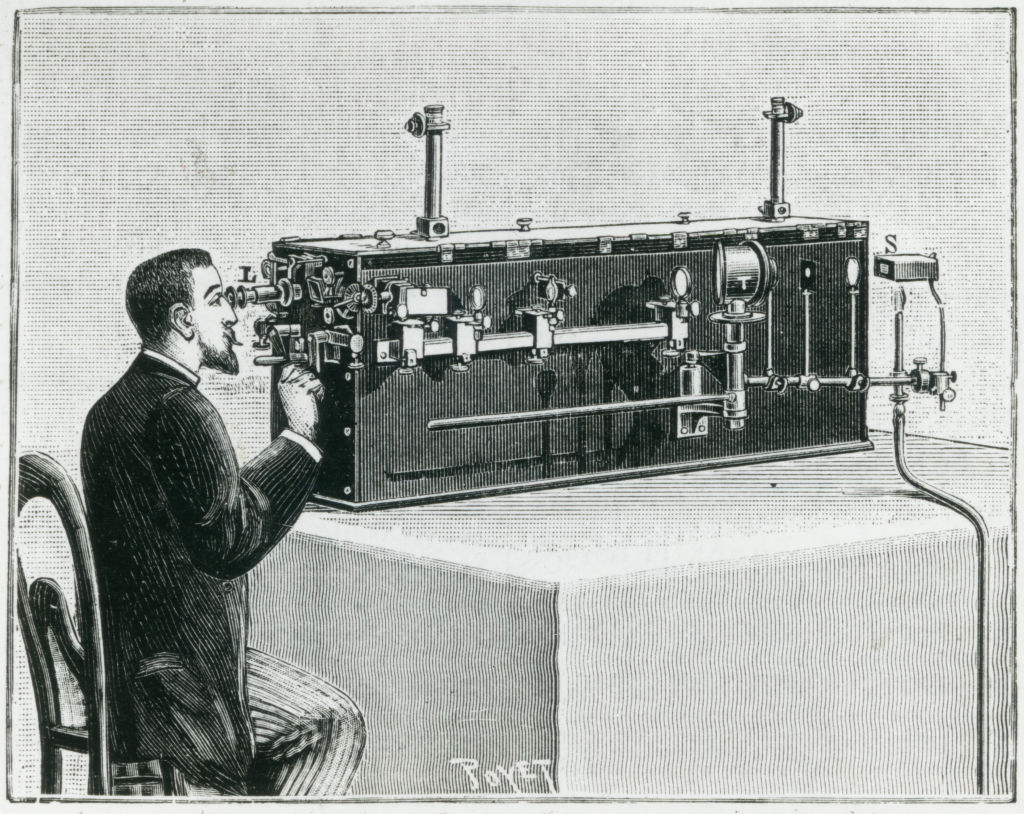

Measurement of the speed of light

Light is the fastest thing in our universe, which makes measuring its speed a unique challenge. In 1676, Danish astronomer Ole Roemer chanced upon the first estimate for light's propagation while studying Io, Jupiter's innermost moon. By timing the eclipses of Io by Jupiter, Roemer was hoping to find the moon's orbital period.

What he noticed instead was that, as Earth's orbit moved closer to Jupiter, the time intervals between successive eclipses became shorter. Roemer's crucial insight was that this was due to a finite speed of light, which he roughly calculated based on Earth's orbit. Other methods later refined the measurement of light's speed, eventually arriving at its current value of 2.98 × 10^8 meters per second (about 186,282 miles per second).

Disproof of the "luminiferous ether"

Most waves, such as sound waves and water waves, require a medium to travel through. In the 19th century, physicists thought the same rule applied to light, too, with electromagnetic waves traveling through a ubiquitous medium dubbed the "luminiferous ether."

Albert Michelson and Edward W. Morley set out to prove this conjecture with a remarkably ingenious hypothesis: As the sun moves through the ether, it should displace some of the strange substance, meaning light should travel detectably faster when it moves with the ether wind than against it. They set up an interferometer experiment that used mirrors to split light beams along two opposing directions before bouncing them back with distant mirrors. If the light beams returned at different times, then the ether was real.

But the light beams inside their interferometer did not vary. Michelson and Morley concluded that their experiment had failed and moved on to other projects. But the result — which had conclusively disproved the ether theory — was later used by Einstein in his theory of special relativity to correctly state that light's speed through a fixed medium does not change, even if its source is moving.

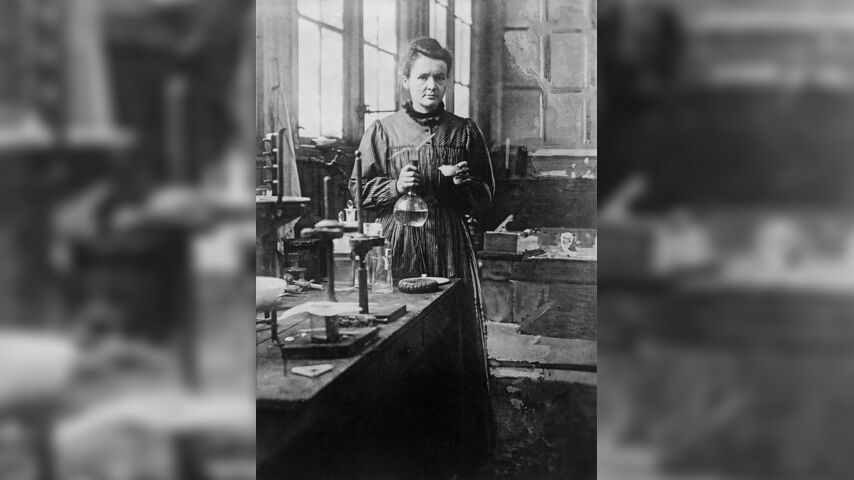

Discovery of radioactivity

In 1897, while working in a converted shed with her husband Pierre, Marie Curie began to investigate the source of a strange new type of radiation emitted from the elements thorium and uranium. Marie Curie discovered that the radiation these elements emitted did not depend on any other factors, such as their temperature or molecular structure, but changed purely based on their quantities. While grinding up an even more radioactive substance known as pitchblende, she also discovered that it consisted of two elements that she dubbed radium and polonium.

Curie's work revealed the nature of radioactivity, a truly random property of atoms that comes from their internal structure. Curie won the Nobel Prize (twice) for her discoveries — making her the first woman to do so — and later trained doctors to use X-rays to image broken bones and bullet wounds. She died of aplastic pernicious anemia, a disease caused by radiation exposure, in 1934.

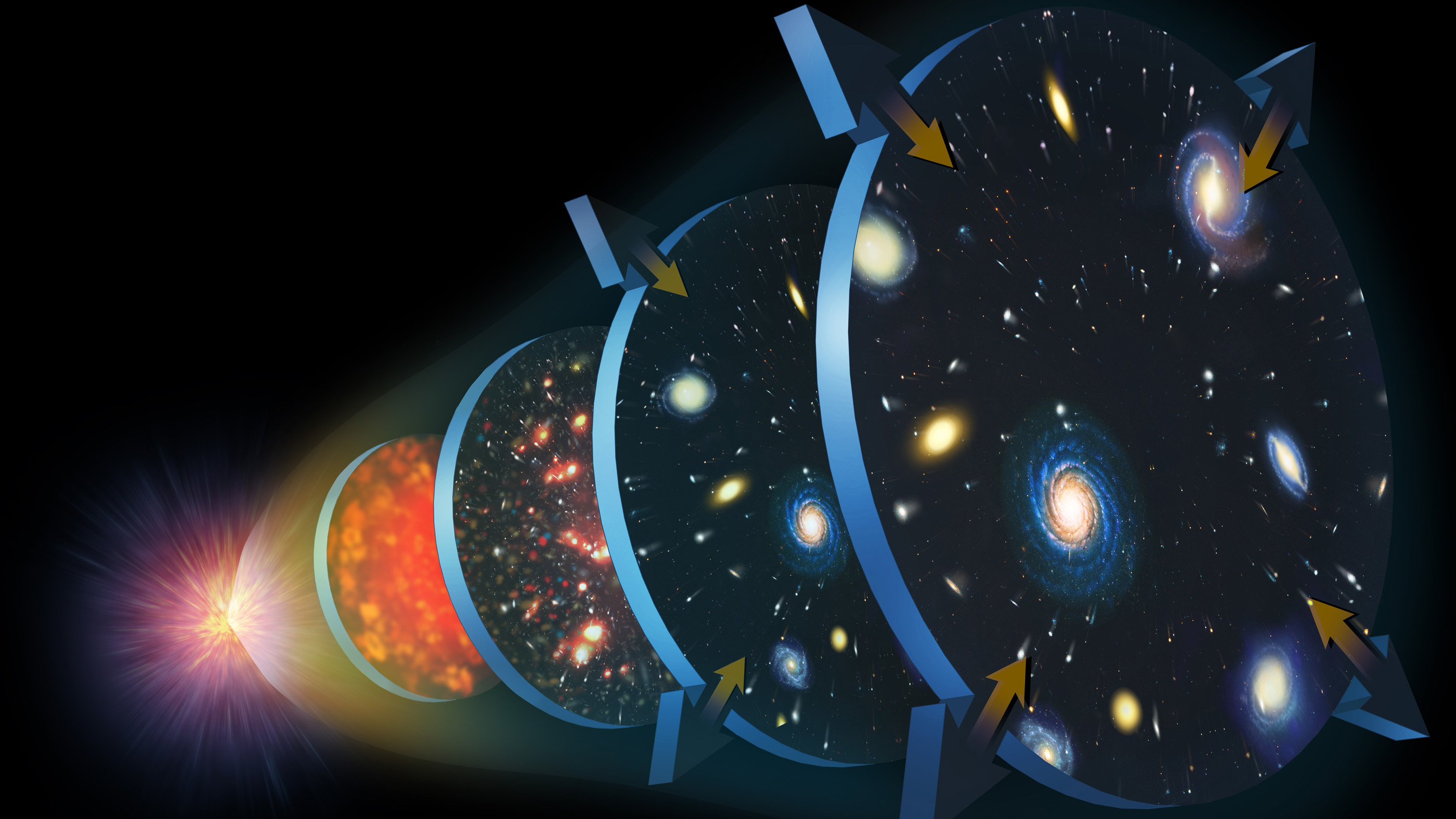

Expansion of the universe

While using the 100-inch Hooker telescope in California to study the light glimmering from distant galaxies in 1929, Edwin Hubble made a surprising observation: The light from the distant galaxies appeared to be shifted toward the red end of the spectrum — an indication that they were receding from Earth and each other. The farther away a galaxy was, the faster it was moving away.

Hubble's observation became a crucial piece of evidence for the Big Bang theory of our universe. Yet precise measurements for galaxies' recession, known as the Hubble constant, still confound scientists to this day.

Put simply, the universe is indeed expanding, but depending on where cosmologists look, it's doing so at different rates. In the past, the two best experiments to measure the expansion rate were the European Space Agency's Planck satellite and the Hubble Space Telescope. The two observatories, each of which used a different method to measure the expansion rate, arrived at different results. These conflicting measurements have led to what some call a "cosmology crisis" that could reveal new physics or even replace the standard model of cosmology.

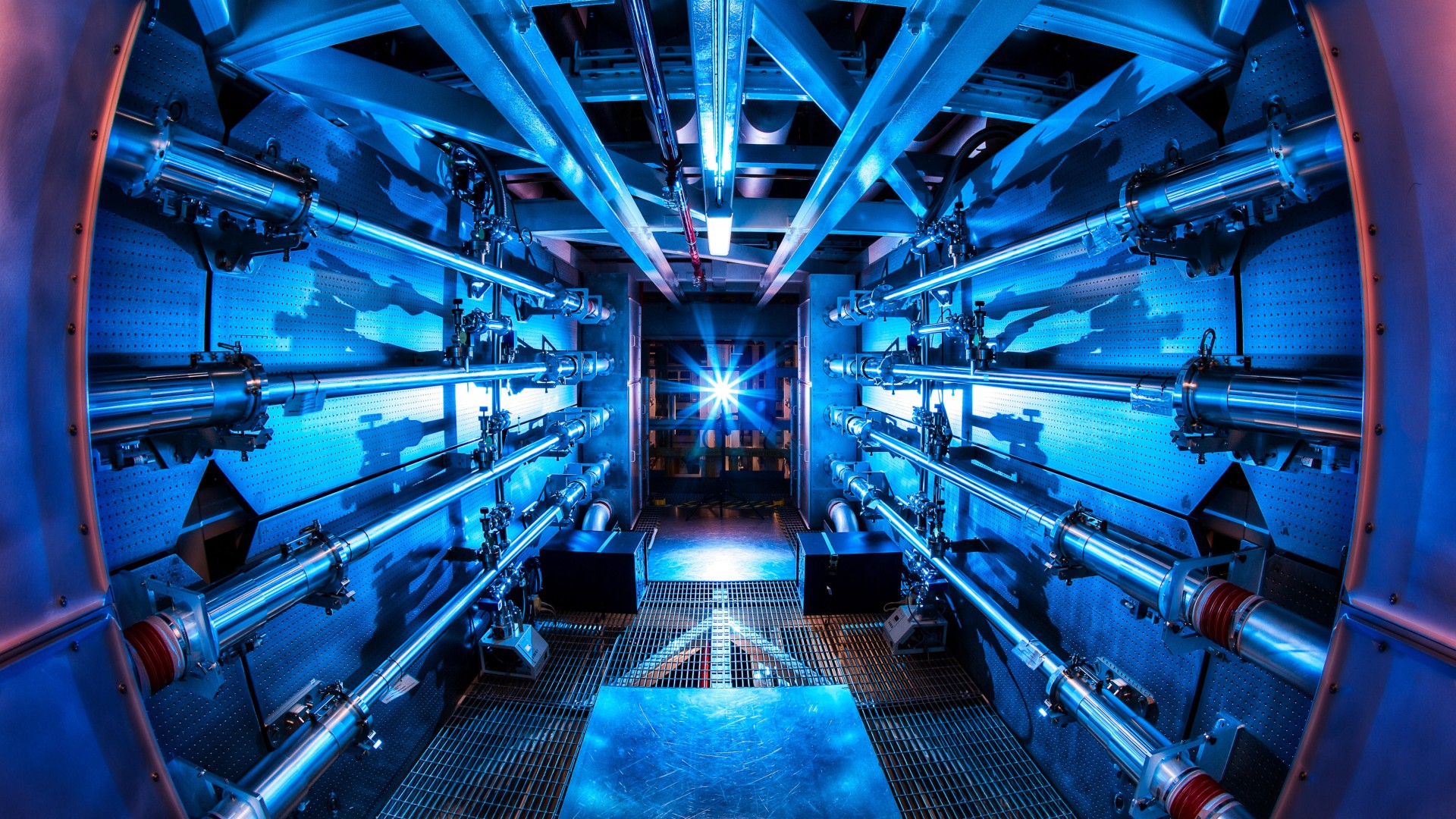

Ignition of nuclear fusion

In 2022, scientists at the National Ignition Facility (NIF) at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California used the world's most powerful laser to achieve something physicists have been dreaming about for nearly a century: the ignition of a pellet of fuel by nuclear fusion.

The demonstration marked the first time that the energy going out of the plasma in the nuclear reactor's fiery core exceeded the energy beamed in by the laser, and has been a rallying call for fusion scientists that the distant goal of near-limitless and clean power is, in fact, achievable.

However, scientists have cautioned that the energy from the plasma exceeds only that from the lasers, and not from the energy from the whole reactor. Additionally, the laser-confinement method used by the NIF reactor, built to test thermonuclear explosions for bomb development, will be difficult to scale up.

Measurement of Earth's circumference

By roughly 500 B.C., most ancient Greeks believed the world was round — citing evidence provided by Aristotle and guided by a suggestion from Pythagoras, who believed a sphere was the most aesthetically pleasing shape for our planet.

Then, around 245 B.C., Eratosthenes of Cyrene thought of a way to make the measurement directly. Eratosthenes hired a team of bematists (professional surveyors who measured distances by walking in equal-length steps called stadia) to walk from Syene to Alexandria. They found that the distance between the two cities was roughly 5,000 stadia.

Eratosthenes then visited a well in Syene that had been reported to have an interesting property: At noon on the summer solstice each year, the sun illuminated the well's bottom without casting any shadows. Eratosthenes went to Alexandria during the solstice, stuck a pole in the ground and measured the shadow from it to be about one-fiftieth of a complete circle. Pairing this with his measurement of the distance between the two cities, he determined that Earth's circumference was about 250,000 stadia, or 24,497 miles (39,424 km). Earth is now known to measure 24,901 miles (40,074 km) around the equator, making the ancient Greeks' measurements remarkably accurate.

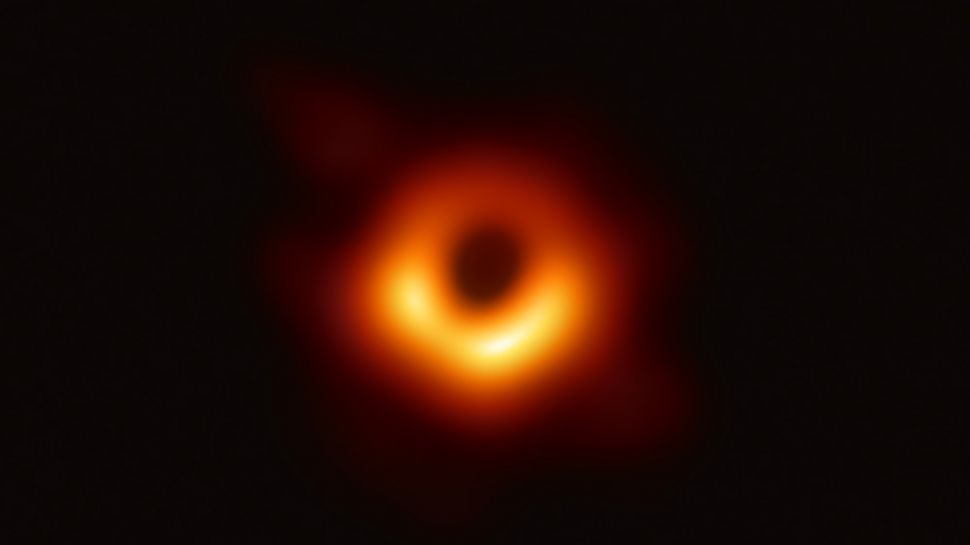

Discovery of black holes

The acceptance of Einstein's theory of general relativity led to some startling predictions about our universe and the nature of reality. In 1915, Karl Schwarzschild's solutions to Einstein's field equations predicted that it was possible for mass to be compressed into such a small radius that it would collapse into a gravitational singularity from which not even light could escape — a black hole.

Schwarzschild's solution remained speculation until 1971, when Paul Murdin and Louise Webster used NASA's Uhuru X-ray Explorer Satellite to identify a bright X-ray source in the constellation Cygnus that they correctly contended was a black hole.

More conclusive evidence came in 2015, when the LIGO experiment detected gravitational waves from two of the colliding cosmic monsters. Then, in 2019, the Event Horizon Telescope captured the first image of the accretion disk of superheated matter surrounding the supermassive black hole at the center of the galaxy M87.

Discovery of X-rays

While testing whether the radiation produced by cathode rays could escape through glass in 1895, German physicist Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen saw that the radiation could not only do so, but it could also zip through very thick objects, leaving a shadow on a lead screen placed behind them. He quickly realized the medical potential of these rays — later known as X-rays — for imaging skeletons and organs. His observations gave birth to the field of radiology, enabling doctors to safely and noninvasively scan for tumors, broken bones and organ failure.

The Bell test

In 1964, physicist John Stewart Bell proposed a test to prove that quantum entanglement — the weird instantaneous connection between two far-apart particles that Einstein objected to as "spooky action at a distance" — was required by quantum theory.

The test has taken many experimental forms since Bell first proposed it, but the findings remain the same: Despite what our intuition tells us, what happens in one part of the universe can instantaneously affect what happens in another, provided the objects in each region are entangled.

Detection of the quark

In 1968, experiments at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center found that electrons and their lepton cousins, muons, were scattering from protons in a distinct way that could only be explained by the protons being composed of smaller components. These findings matched predictions by physicist Murray Gell-Mann, who dubbed them "quarks" after a line in James Joyce's "Finnegans Wake."

Archimedes' naked leap from his bathtub

First recorded in the first century B.C. by Roman architect Vitruvius, Archimedes' discovery of buoyancy is one of the most famous stories in science. The prompting for Archimedes' finding came from King Hieron of Syracuse, who suspected that a pure-gold crown a blacksmith made for him actually contained silver. To get an answer, Hieron enlisted Archimedes' help.

The problem stumped Archimedes, but not long after, as the story goes, he filled up a bathtub with water and noticed that the water spilled out as he got in. This caused him to realize that the water displaced by his body was equal to his weight — and because gold weighed more than silver, he had found a method for judging the authenticity of the crown. "Eureka!" ("I've got it!") Archimedes is said to have cried, leaping from his bathtub to announce his discovery to the king.

Deepest and most detailed photo of the universe

In 2022, the James Webb Space Telescope unveiled the deepest and most detailed picture of the universe ever taken. Called "Webb's First Deep Field," the image captures light as it appeared when our universe was just a few hundred million years old, right when galaxies began to form and light from the first stars started flickering.

The image contains an overwhelmingly dense collection of galaxies, the light from which, on its way to us, was warped by the gravitational pull of a galaxy cluster. This process, known as gravitational lensing, brings the fainter light into focus. Despite the dizzying number of galaxies in view, the image represents just a tiny sliver of sky — the speck of sky blocked out by a grain of sand held on the tip of a finger at arm's length.

OSIRIS-REx asteroid-sampling mission

In 2023, NASA's OSIRIS-REx spacecraft came hurtling back through Earth's atmosphere after a years-long journey to Bennu, a "potentially hazardous asteroid" with a 1-in-2,700 chance of smashing cataclysmically into Earth — the highest odds of any identified space object.

The goal of the mission was to see whether the building blocks for life on Earth came from outer space. OSIRIS-REx circled the asteroid for 22 months to search for a landing spot, touching down to collect a 2-ounce (60 grams) sample from Bennu's surface that could contain the extraterrestrial precursors to life on our planet. Scientists have already found many surprising details that have the potential to rewrite the history of our solar system.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.