How fast is a bullet?

The answer depends on the design of the bullet and the gun, as well as on what happens once the bullet leaves the muzzle.

Superman flies "faster than a speeding bullet," and "bullet" trains zoom between cities at spectacular speed. The comparison is ubiquitous, yet the exact velocity is far less cited. So how fast do bullets actually travel?

Many factors influence the speed of a bullet when it's fired from a gun. They tend to fall into two categories: internal ballistics — including the type of propellant, the bullet's weight, and the shape and length of the gun's barrel — and external ballistics, or the forces that wind, gravity and trajectory exert over a projectile as it moves through the air. Both feed into a third category, called terminal ballistics, that describes a bullet's behavior when it strikes a target.

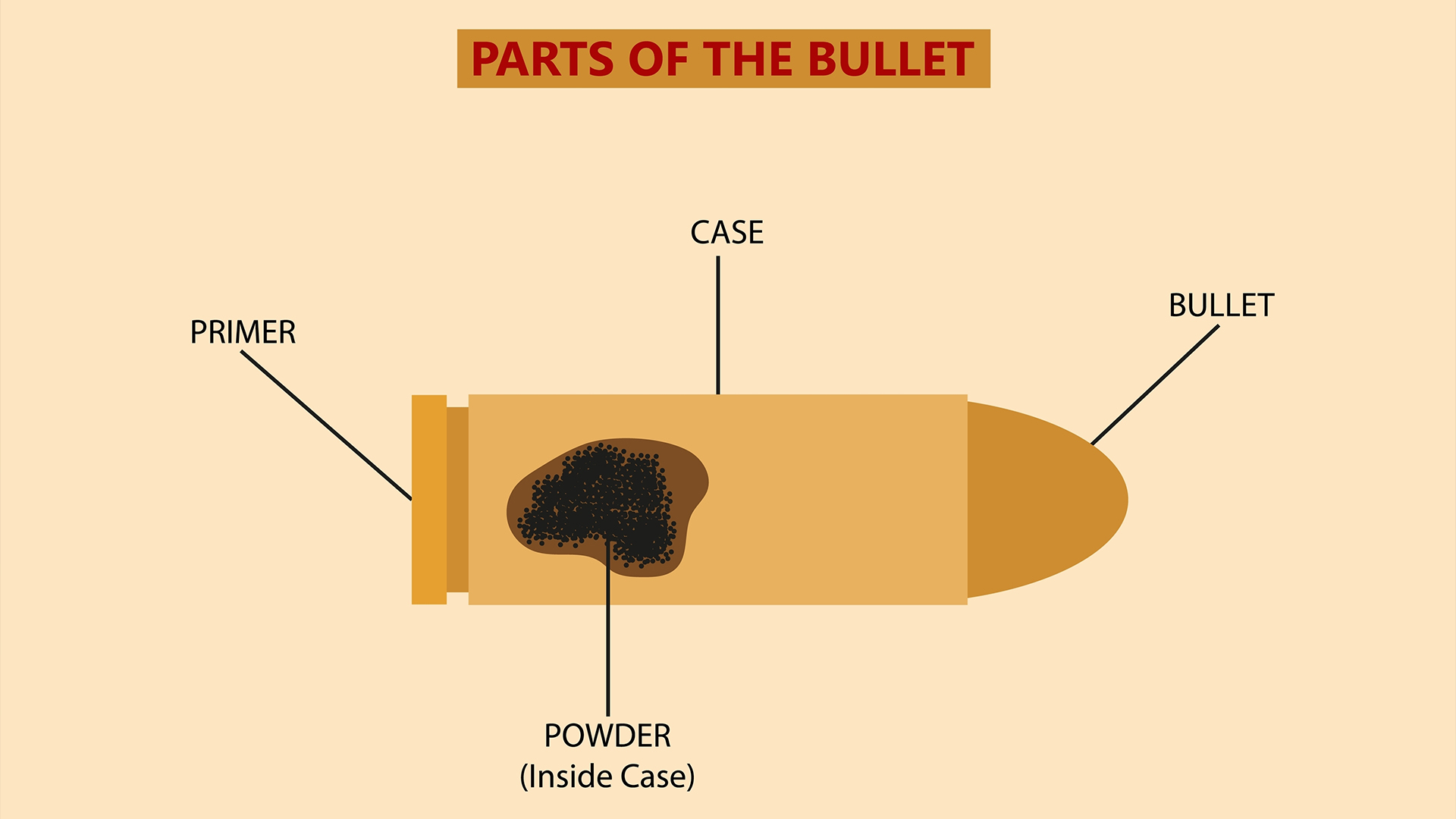

The term "bullet" actually refers to only a small part of a much larger cartridge, Michael Haag, a forensic scientist and founder of Forensic Science Consultants, told Live Science. Ammunition is made up of a primer that ignites a propellant when struck by the gun's firing pin, and this ignition creates the pressure that drives a projectile forward. Most bullets are made with heavy metals such as lead, jacketed by brass or copper, because their mass helps them hold their momentum. To illustrate this point, Haag often instructs juries to imagine throwing a ping-pong ball and a golf ball: Both leave your hand at the same speed, but the mass of the golf ball causes it to travel farther.

As soon as gunpowder ignites, it burns very quickly, generating gases that push the bullet down the barrel. "It's really a chemical engineering marvel," Haag said.

Related: What is the fastest animal on Earth?

As the bullet moves toward the muzzle, it scrapes down the barrel's sides, which introduces some friction. But, somewhat counterintuitively, guns with longer barrels produce the fastest shots. "The barrel is really the biggest limiting factor on speed," said Stephanie Walcott, a forensic scientist at Virginia Commonwealth University. "The longer the barrel, the longer the distance that gas has to build velocity, and the faster the bullet is going to leave the barrel."

For this reason, rifles tend to generate the most speed. Rifles are meant to be used over long distances, and a bullet fired from one can travel as far as 2 miles (3.2 kilometers). To achieve these shots, rifle bullets are designed to be aerodynamic, making them longer, thinner and heavier than handgun bullets. Gun manufacturers sometimes add helical ridges to the inside of the barrel that cause the bullet to spin — like a quarterback throwing the perfect spiral — thus stabilizing its horizontal flight.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These collective features mean that rifle bullets, such as that of a Remington 223, leave the muzzle at speeds of up to 2,727 mph (4,390 km/h) — fast enough to cover the distance of 11 football fields in a single second. A bullet from a 9mm Luger handgun, by comparison, would cover half that distance at speeds of up to 1,360 mph (2,200 km/h). Something like an AK-47, among the most common firearms in the world, doesn't fire bullets any faster than many other rifles, with a muzzle velocity of about 1,600 mph (2,580 km/hr). But because it's an automatic weapon, it fires continuously until the trigger is released, and can eject up to 600 rounds per minute.

As soon as a bullet leaves the muzzle, it's already begun to slow down, Walcott said. That's because, per Newton's first law, an object in motion will stay in motion unless acted upon by an external force. Among the forces acting on a bullet once it is fired are air resistance, gravity and gyroscopic motion. Over time, the first two factors overcome the bullet's innate tendency to remain in a consistent spiral, and the bullet begins to tumble. All bullets have a so-called ballistics coefficient that determines their ability to overcome air resistance and fly forward, and the equation factors in a bullet's mass, area, drag coefficient (a measure of the effectiveness of a bullet's shape in reducing air resistance), density and length. The higher the ballistics coefficient, the better the bullet is at cutting through air.

"But it doesn't take long before gravity and air drag really start setting in and slowing that bullet down," Walcott told Live Science. "It's going to go very straight for a time, and then it's going to start dropping off and becoming sensitive to the environment around it."

Amanda Heidt is a Utah-based freelance journalist and editor with an omnivorous appetite for anything science, from ecology and biotech to health and history. Her work has appeared in Nature, Science and National Geographic, among other publications, and she was previously an associate editor at The Scientist. Amanda currently serves on the board for the National Association of Science Writers and graduated from Moss Landing Marine Laboratories with a master's degree in marine science and from the University of California, Santa Cruz, with a master's degree in science communication.