The world's largest atom smasher is getting a powerful new upgrade

Physicists are finalizing plans for MATHUSLA, a powerful new addition to CERN's Large Hadron Collider that will detect long-lived particles and potentially open the door to new physics.

The world's biggest atom smasher could be getting an upgrade.

The Large Hadron Collider (LHC), situated at the CERN laboratory on the Swiss-French border, was built over a decade ago with two goals in mind. First, to establish the existence of the Higgs boson, the cornerstone particle of the Standard Model of particle physics, predicted all the way back in the 1960s; And second, to find any new particles, especially ones that could validate one of the many competitors to physical theories beyond the Standard Model.

But while the LHC has proven a success when it comes to the Higgs, whose existence was confirmed by CERN scientists in 2012, the atom smasher has also been a failure when it comes to new particles. Despite more than a decade of searching, the collider has found no traces of any physics beyond the Standard Model.

Failing to find new particles is not exactly a bad thing. The continuous negative results have disproven many alternative models, which means that at least scientists know which ideas are bad and no longer worth working on. But a lack of positive results has also left modern particle physics in the dark, with little to no clues about which hypothetical ideas might still be worth pursuing.

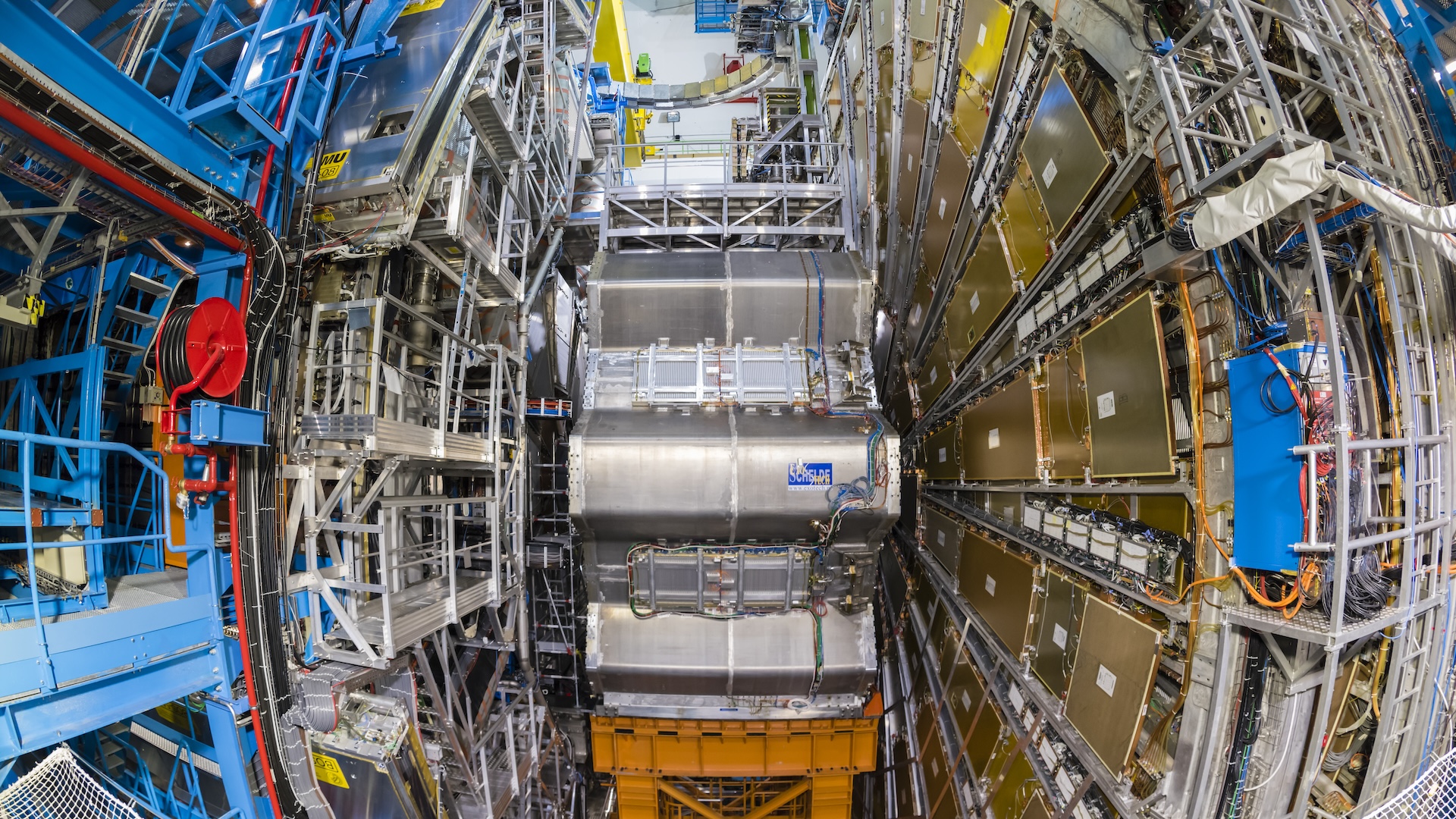

The LHC, as powerful as it is at seeing subatomic particles, does have a blind spot. It was designed with certain hypothetical particles in mind, especially ones that have electric charge and don't have long lifespans. And there is a class of hypothetical particles, known as long-lived neutral particles, that can slip by LHC's two main detectors without notice. So the giant machine may have been revealing new physics every single day, but those particles were undetectable.

This fact was not lost on the LHC's original designers. Soon after the collider began operations, a team gathered to design an add-on detector to look for long-lived particles. That detector, known as MATHUSLA — named for Methuselah, the Biblical character who supposedly lived for over 900 years, and stands for MAssive Timing Hodoscope for Ultra-Stable neutraL pArticles — is in its final design stages, according to a report by more than 30 scientists involved in the project, published March 26 to the preprint server arXiv.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

If funding stays on track, the team hopes to begin construction this year.

Waking MATHUSLA

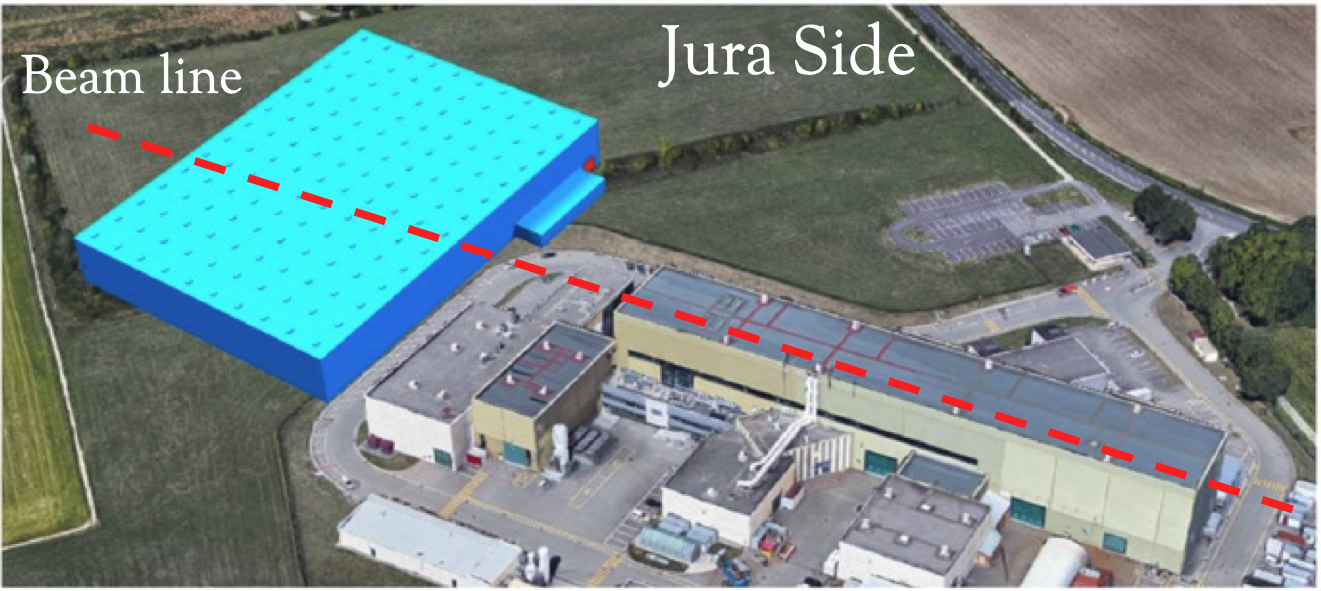

MATHUSLA will consist of a giant chamber 130 feet (40 meters) across, filled with nothing but air and surrounded by banks of detectors. It would be placed about 330 feet (100 m) away from the main collider beam, with dirt and rock filling the space between.

In particle physics, "long-lived" is a relative term. In this case, many hypothetical particles have lifespans of around a few hundred nanoseconds — an eternity compared to the vast majority of particles that are currently being studied at the LHC.

If MATHULSA works, the add-on detector will wait for one of these long-lived particles to make its way into the main chamber. There it will decay into a shower of other particles, and banks of sensors will look for their telltale glow.

Long-lived particles could give physicists insights into the detailed nature of the Higgs boson, possible companions to the Higgs and explanations as to why the force of gravity is so weak. They may even help reveal the identity of dark matter — the mysterious substance that is predicted to make up about 85% of all matter in the universe and yet remains largely unknown to science.

With such exciting results potentially within reach, let's just hope that we won't have to wait 900 years for MATHUSLA to be built.

Paul M. Sutter is a research professor in astrophysics at SUNY Stony Brook University and the Flatiron Institute in New York City. He regularly appears on TV and podcasts, including "Ask a Spaceman." He is the author of two books, "Your Place in the Universe" and "How to Die in Space," and is a regular contributor to Space.com, Live Science, and more. Paul received his PhD in Physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2011, and spent three years at the Paris Institute of Astrophysics, followed by a research fellowship in Trieste, Italy.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.