Pig kidney successfully hooked up to human patient in watershed experiment

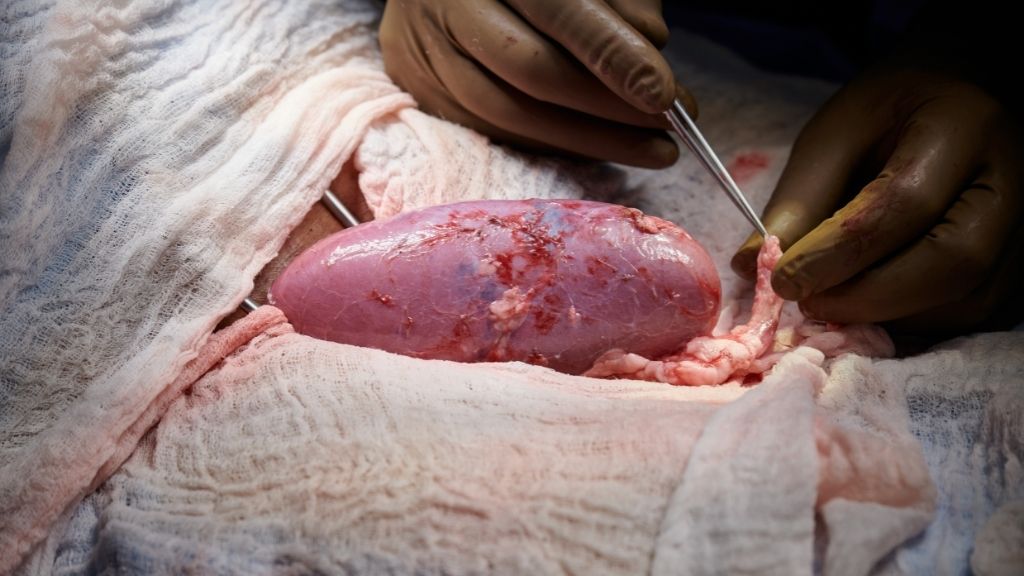

In a groundbreaking experiment, scientists hooked up a genetically modified pig kidney to a human patient and watched as the organ successfully filtered waste from the person's body.

The experiment was conducted in a brain-dead patient who was a registered organ donor and whose family granted permission for the procedure to be done, The New York Times reported. During the 54-hour experiment, the kidney remained outside the patient's body where the surgeons could observe the organ and take tissue samples. Although the kidney wasn't implanted inside the body, the procedure still allowed the team to see whether the organ would be immediately rejected; problems with animal-to-human transplants typically develop where the human blood interfaces with the animal tissue, such as in the blood vessels, experts told the Times.

Compared with primate organs, pig organs offer a number of advantages for transplantation. For example, pigs are already raised for food, produce large litters within a short gestation period and grow strikingly similar organs to humans', The Associated Press (AP) reported. But there's one major hurdle: Pig tissues carry a gene that codes for a sugar molecule called alpha-gal, which can send the human immune system into a frenzy and lead to organ rejection. (In people with a rare red meat allergy, alpha-gal can trigger life-threatening allergic reactions, Live Science previously reported.)

Related: How long can organs stay outside the body before being transplanted?

So in the transplant experiment, conducted last month, the team used a kidney from a genetically engineered pig that lacked this sugar-producing gene. To prepare the organ for transplant, the team modified the kidney in one additional way: they transplanted the pig's thymus, a small gland that helps train immune cells to fight infection, into the kidney, Dr. Robert Montgomery, who led the surgical team at NYU Langone Health, explained in a press conference held on Oct. 21.

Previous transplant studies in primates have hinted that, by moving the donor animal's thymus into a transplant recipient, this can help "reeducate" the recipient's immune system so the body accepts the transplant in the long-term, Montgomery said. That's why, in future, long-term trials with living participants, the team plans to use pig kidneys equipped with thymus glands, and that's why they used the same in this shorter experiment.

That said, for the 54-hour experiment, the team was watching out for a more immediate immune response against the kidney, where antibodies in the human blood supply attack the organ upon entry. But thankfully, no such attack took place, and instead, the kidney began producing large amounts of urine within minutes of being plugged into the patient's vessels.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It had absolutely normal function," Montgomery told the AP. As soon as it was attached to blood vessels in the patient's upper leg, the pig kidney began filtering creatinine, a waste product of muscle cell function, from the blood and quickly brought the creatinine levels down to a normal range. "It didn't have this immediate rejection that we have worried about."

Given the promising results, the experiment could represent a big step forward for xenotransplants — transplants from animals to humans — but many questions remain.

"We need to know more about the longevity of the organ," Dr. Dorry Segev, a professor of transplant surgery at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine who was not involved in the research, told the Times. Kidney rejection can occur long after a transplant "even when you're not trying to cross species barriers," so the durability of pig-to-human transplants will need to be carefully assessed, Dr. David Klassen, chief medical officer of the United Network for Organ Sharing, told the Times.

But if and when pig-to-human transplants can be cleared for wider use, "it's truly mind-boggling to think of how many transplants we might be able to offer," Dr. Amy Friedman, a former transplant surgeon and chief medical officer of LiveOnNY, a New York-based organ procurement organization, told the Times. Last year, 23,401 U.S. residents received kidney transplants, and currently, 90,240 Americans are on a waitlist for a kidney, the Times reported. Many patients with kidney failure can't qualify to get on a list, in part, due to the scarcity of available kidneys.

Pig kidneys could potentially make transplants available to many more people, but "you'd have to breed the pigs, of course," Friedman said.

Revivicor, a subsidiary of United Therapeutics, developed the genetically modified pig used in the recent transplant; the company's so-called GalSafe pigs were cleared for medical use and consumption by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration last year, the AP reported in December 2020. Revivicor has no immediate plans to sell the pigs as food, but the product could potentially be appealing to those with alpha-gal allergies, for instance.

In the future, the gene editing tool CRISPR could also make pig organ transplants safer, Live Science previously reported. Meanwhile, some labs are taking a very different approach to the transplant problem: growing human tissues and organs inside pigs so that they can later be harvested for transplants. In theory, because the organs would be made of human cells, they'd be less prone to rejection. However, the development of such human-pig chimeras is still in its early days and raises a number of ethical concerns.

Read more about the transplant experiment in The New York Times and The Associated Press.

Editor's note: This story was updated on Oct. 21 to clarify how the pig's thymus was used in the study, based on details shared by Dr. Robert Montgomery in a press conference held the same day. The original story was published on Oct. 20.

Originally published on Live Science.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.