Living fossil with arms made of 'pig snouts' discovered in the South Pacific

An eight-armed, pig-snouted brittle star found in the depths of the South Pacific has roots reaching back to the days of the dinosaurs.

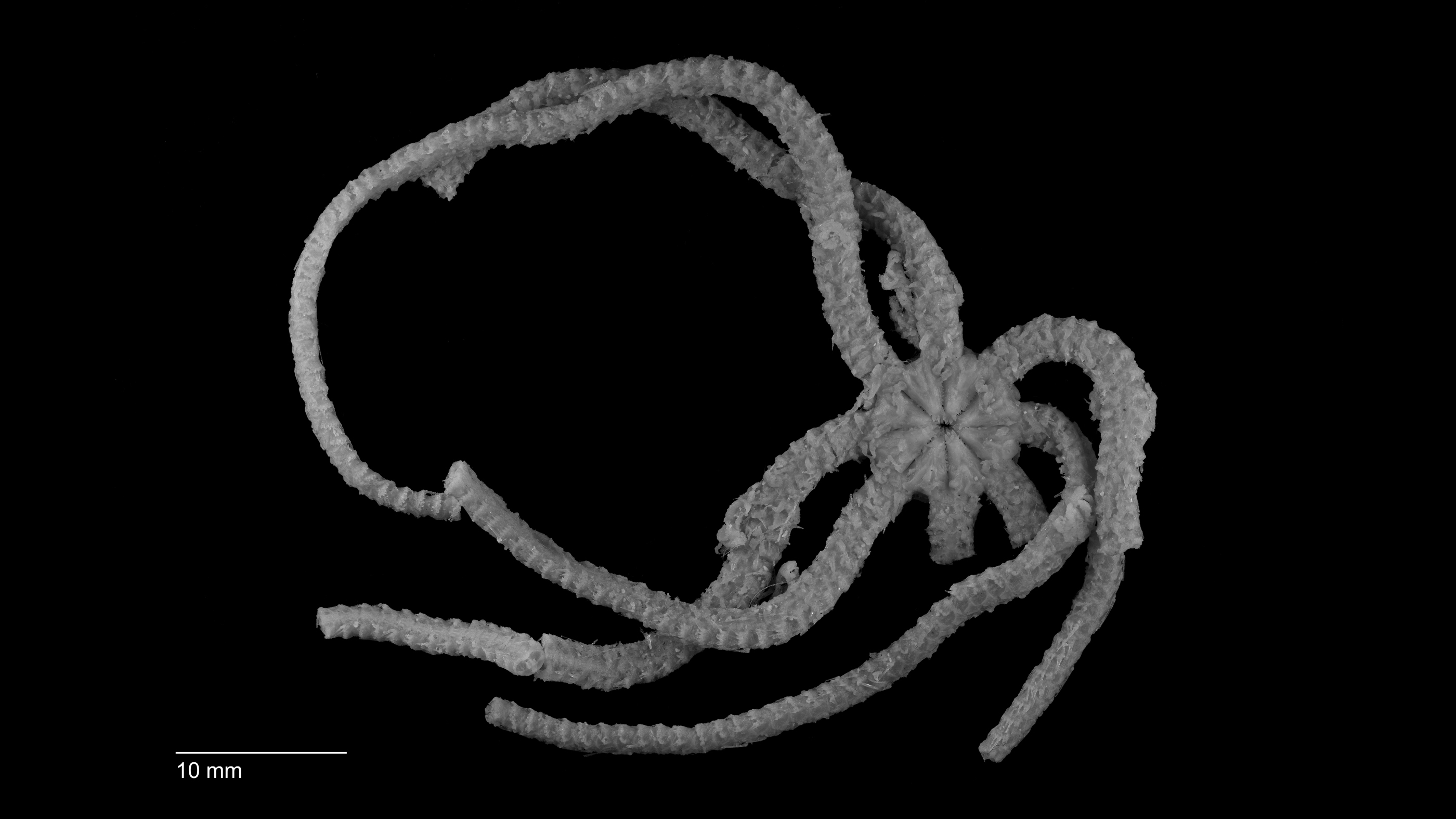

The brittle star, which has a body just 1.1 inch (3 centimeters) in diameter and arms approximately 3 inches (8 cm) long, represents a completely new family of these starfish relatives — one with members dating back 180 million years, to the Jurassic period.

The brittle stars may lurk in an environment 1,180 feet to 1,837 feet (360 to 560 meters) deep that hasn't changed much in millions of years. The tropics at this depth seem to be a ripe spot for discovering evolutionary relicts, or surviving species of very old groups of organisms, said study leader Tim O'Hara, invertebrate curator at Museums Victoria in Melbourne, Australia.

"This is probably because tropical environments are very old, dating back to the dinosaur era, and haven't changed much," O'Hara told Live Science. "This allows some of these 'living fossils' to persist into our time."

Related: Ancient footprints to tiny 'vampires': 8 rare and unusual fossils

(Star)fish in a barrel

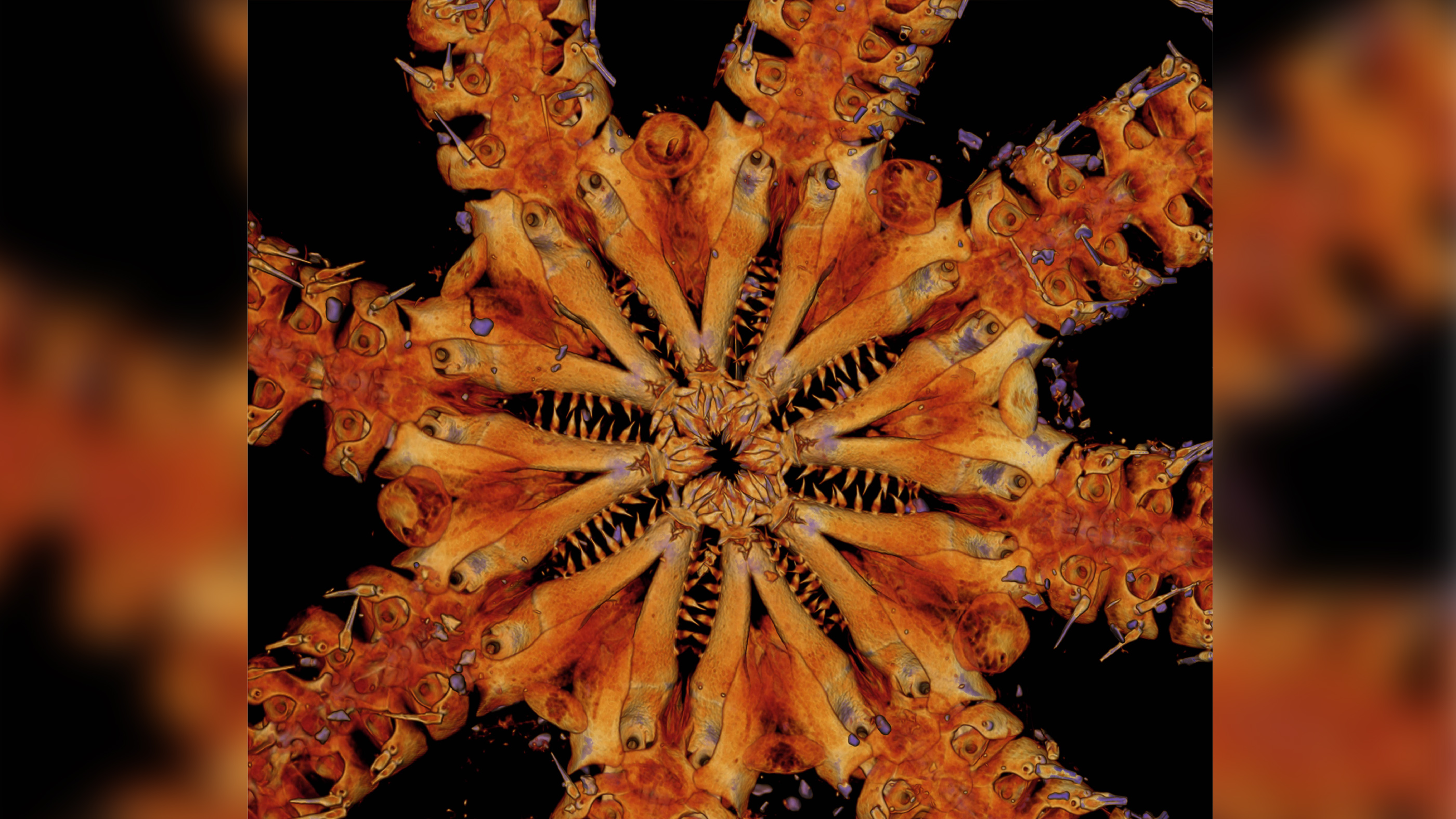

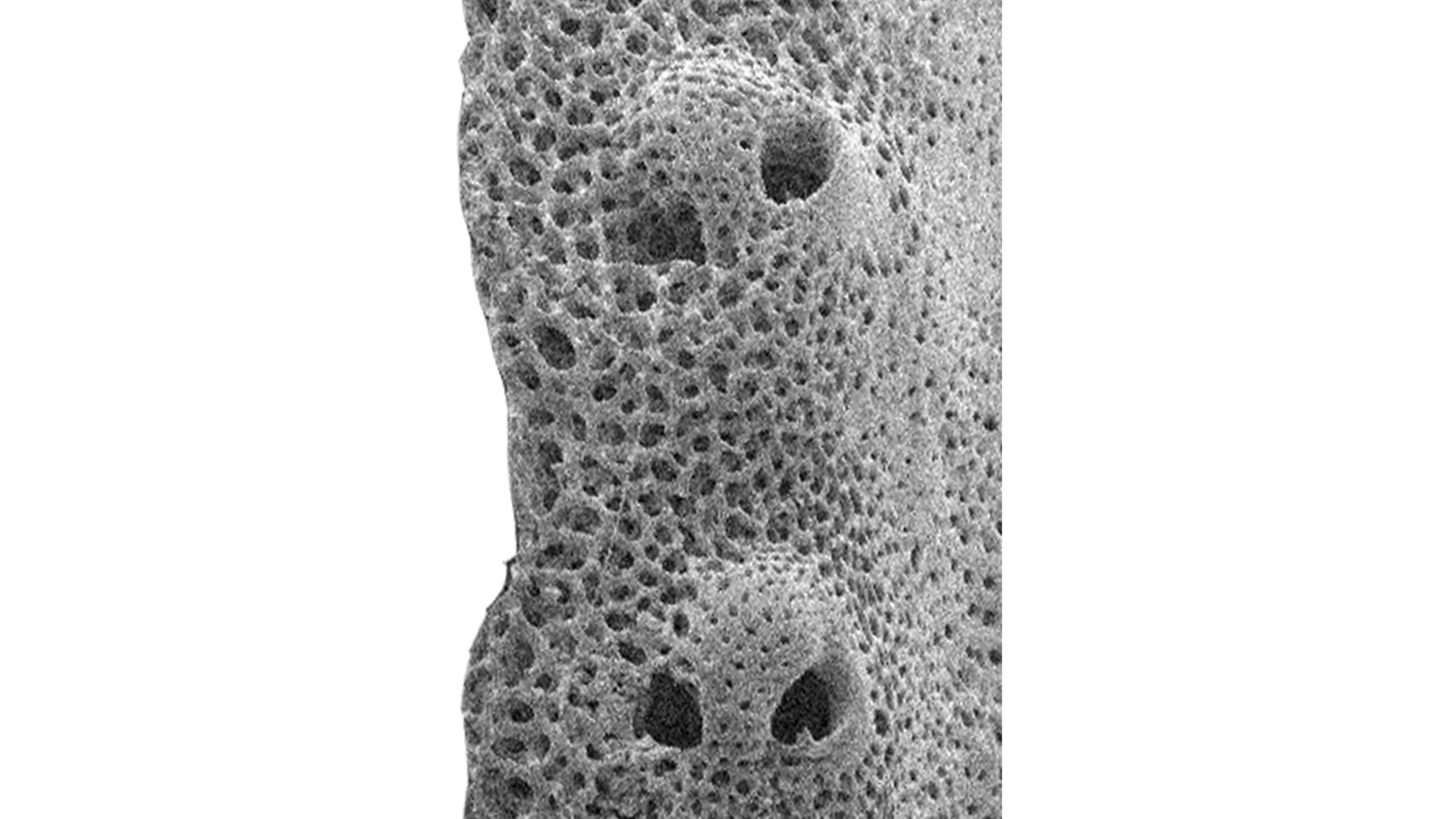

O'Hara discovered the brittle star in 2015, in a barrel of unidentified specimens stored in the French National Museum of Natural History in Paris. The specimen was collected in 2011, during an expedition to New Caledonia, a French territory in the South Pacific. Scientists had used a large net called a beam trawl to scope samples from the seafloor of a volcanic ridge named Banc Durand and turned up the new brittle star. The specimen was strange, with eight arms instead of five or six, as is more typical for brittle stars. It had long jaws on the underside of its body, bristling with teeth. And its arms had an odd skeletal pattern that looked as if they were built from dozens of tiny pig snouts snapped together.

"Even from the first look, I could see that it was different from all other brittle stars that I was looking at," O'Hara said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

After sequencing the specimen's DNA, O'Hara and his colleagues realized the brittle star was not closely related to known species of echinoderms, the group that includes previously known brittle stars, starfish and other symmetrical bottom dwellers, like sand dollars.

Jurassic star

That's when study co-author Ben Thuy, a paleontologist at the Luxembourg National Museum of Natural History, realized he'd seen the bizarre pig-snouted pattern on the brittle star's arms before. At first, he couldn't figure out why they seemed familiar, O'Hara said, but then he saw a strikingly similar photograph of fossils found in northern France that he had put on a scientific poster years before.

The anatomical similarity revealed that the brittle star had relatives reaching back 180 million years, when the supercontinent Pangaea was breaking up and opening new oceans. The researchers created a new family, which they dubbed Ophiojuridae, to fit these new species. The name comes from "Ophio," the ancient Greek word for "serpent," and from the Jura Mountains in Europe, where the geology of the Jurassic was first defined.

They named the living species Ophiojura exbodi, with "exbodi" referring to the acronym for the scientific expedition that discovered the brittle star.

They might have named it "shredder," though. The brittle star probably feeds by extending its arms into the water to capture plankton such as tiny shrimps. A layer of mucus probably covers the arms, allowing it to stick to prey. Additional spiky projections on the arms act like meat hooks to ensnare passing plankton, O'Hara added. Rows and rows of sharp teeth are probably used to shred prey, he said.

The research appeared June 16 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B. New Caledonia is still being surveyed, O'Hara said, raising hopes that this won't be the last dinosaur-era living fossil found in the region.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.