Siberia's 'gateway to the underworld' megaslump is revealing 650,000 year-old secrets from its permafrost

The permafrost inside the Batagay crater is the second-oldest ever found on Earth and scientists are using it to reconstruct the planet's ancient climate.

Ground that has been frozen for 650,000 years is the oldest permafrost in Siberia — and the second-oldest ever discovered on Earth, scientists have discovered.

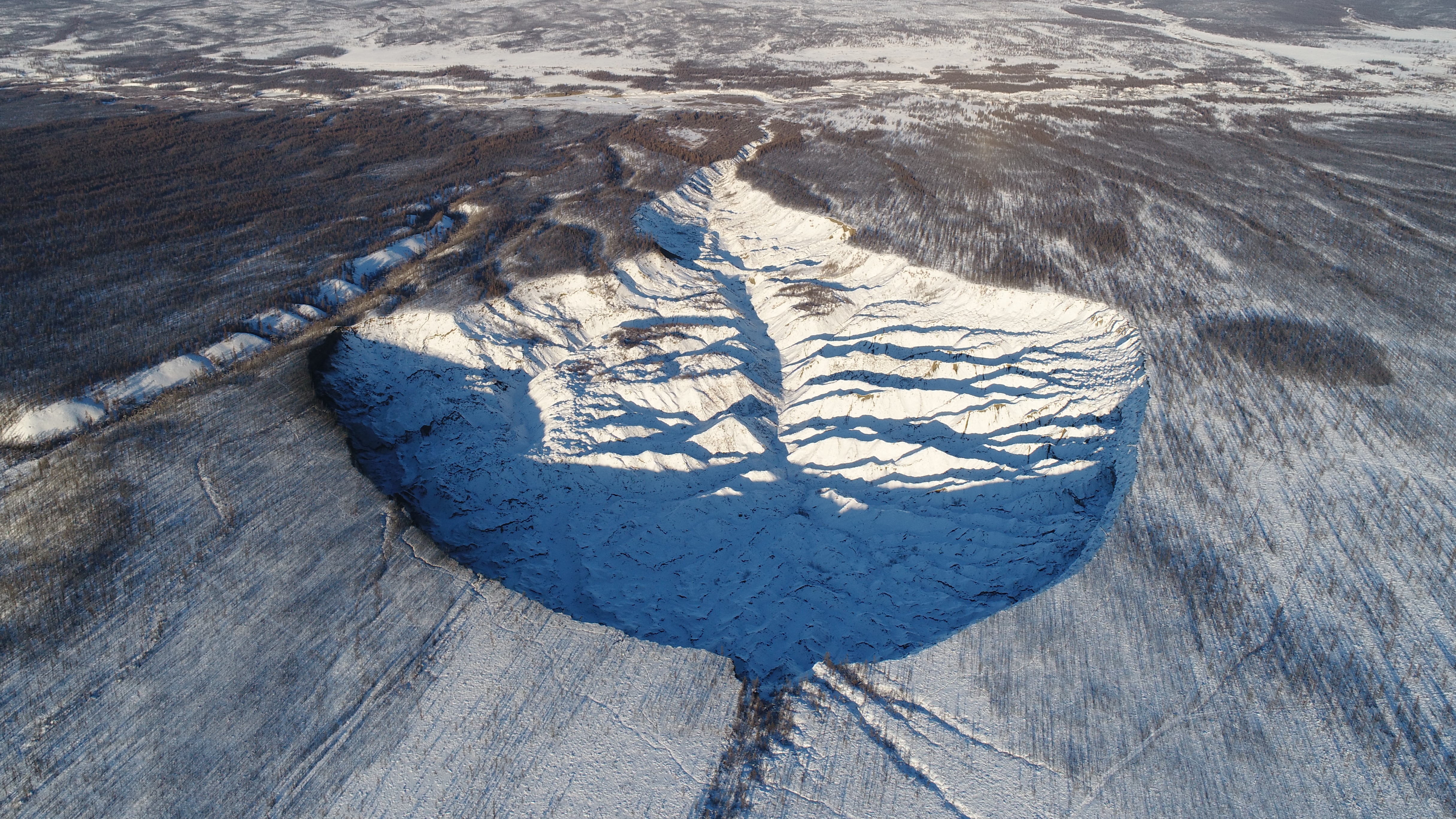

The researchers took samples from the Batagay megaslump, a huge collapsed section of hillside in the Yana Uplands of northern Yakutia, Russia that is known to locals as the "gateway to the underworld."

The slump is a stark badlands in the midst of larch-and-birch woodlands. Deforestation, which started in the 1940s, led to erosion, which in turn caused increased seasonal melting of the permafrost in the frigid region, where winter temperatures average minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 40 degrees Celsius). The permafrost in this region is 80% ice, so the significant amounts of melt caused the sediment in the hillside to collapse, said Thomas Opel, a paleoclimatologist at the Alfred Wegener Institute in Germany.

Related: 8 ancient 'zombie viruses' that scientists have pulled from the melting permafrost

Over the years, the Batagay megaslump has grown to cover 0.3 square miles (0.8 square kilometers), making it the largest megaslump on Earth. The slump’s headwall, the cliff at the top end of the formation, is 180 feet (55 meters) high.

Permafrost is ground that has been permanently frozen for at least two years. Studying it provides a window into the past and the future by showing how it responded to previous climate change events.

Batagay is important, Opel told Live Science, because its sediments preserve a long, if broken, record of ancient environment and climate. There is one site in Canada's Yukon with permafrost slightly older than 700,000 years, he said, and there is a continuous record of ice in Greenland that goes back 130,000 years. But there are few very old permafrost layers discovered in Siberia.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We can now just add another site to the map so that we can really start reconstructing the climate and also the environment for this period of time," Opel said.

The researchers announced their findings in a study published in Quaternary Research in 2021. They presented their latest results at the European Geosciences Union General Assembly in April this year.

The researchers used three dating methods to reveal the age of the permafrost layers. The first, radiocarbon dating, measures the decay of the carbon-14 isotope over time, providing an accurate window stretching back about 60,000 years.

To get older dates, they turned to two other methods. Chlorine-36 dating uses the decay of a molecular variation of chlorine in ice to mark time. Luminescence dating, meanwhile, takes advantage of the energy of photons stored inside mineral crystals that have been buried underground. When this energy is released, it can reveal how long ago the sediments last encountered sunlight. These methods can provide dates on materials going back 500,000 to 1 million years.

The measurements revealed that the oldest accessible layers of permafrost in the slump were laid down 650,000 years ago, during the largest glacial period in the Northern Hemisphere of the last million years. There is then a gap in the record until about 200,000 years ago. It's not clear, Opel said, whether the intervening years of permafrost melted, or if there was simply no additional permafrost added in that time period.

The researchers found another gap in the permafrost about 130,000 years ago — which was not surprising, as this was a warm interglacial period on Earth, Opel said.

Studying the permafrost from immediately before and after that period could reveal more about modern-day climate change.

"Given the fact that there is so much ancient carbon in the permafrost we hope we can help a little bit to predict how permafrost could react to climate change in the future," Opel said.

The permafrost can also offer scientists a glimpse into animals and plants from the past. In 2018, scientists found a 40,000-year-old Pleistocene horse (Equus lenensis) foal dangling out of this cliffside that was so well-preserved it looked like it was freshly dead.

The oldest animal and plant remains in the Batagay layers come from the past 60,000 years or so, Opel said. But he and his colleagues are studying the older layers, looking at both the chemistry and analyzing any ancient DNA that might still remain.

"There is certainly more to come," Opel said.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.