Experts are certain 2023 will be 'the warmest year in recorded history'

After the warmest autumn ever, researchers are confident 2023 will be the hottest year on record before it has even finished.

Before the year has even come to a close, climate experts are certain that 2023 will be the hottest year in recorded history. And while several factors are impacting this year's record heat, researchers say human-caused climate change is overwhelmingly responsible.

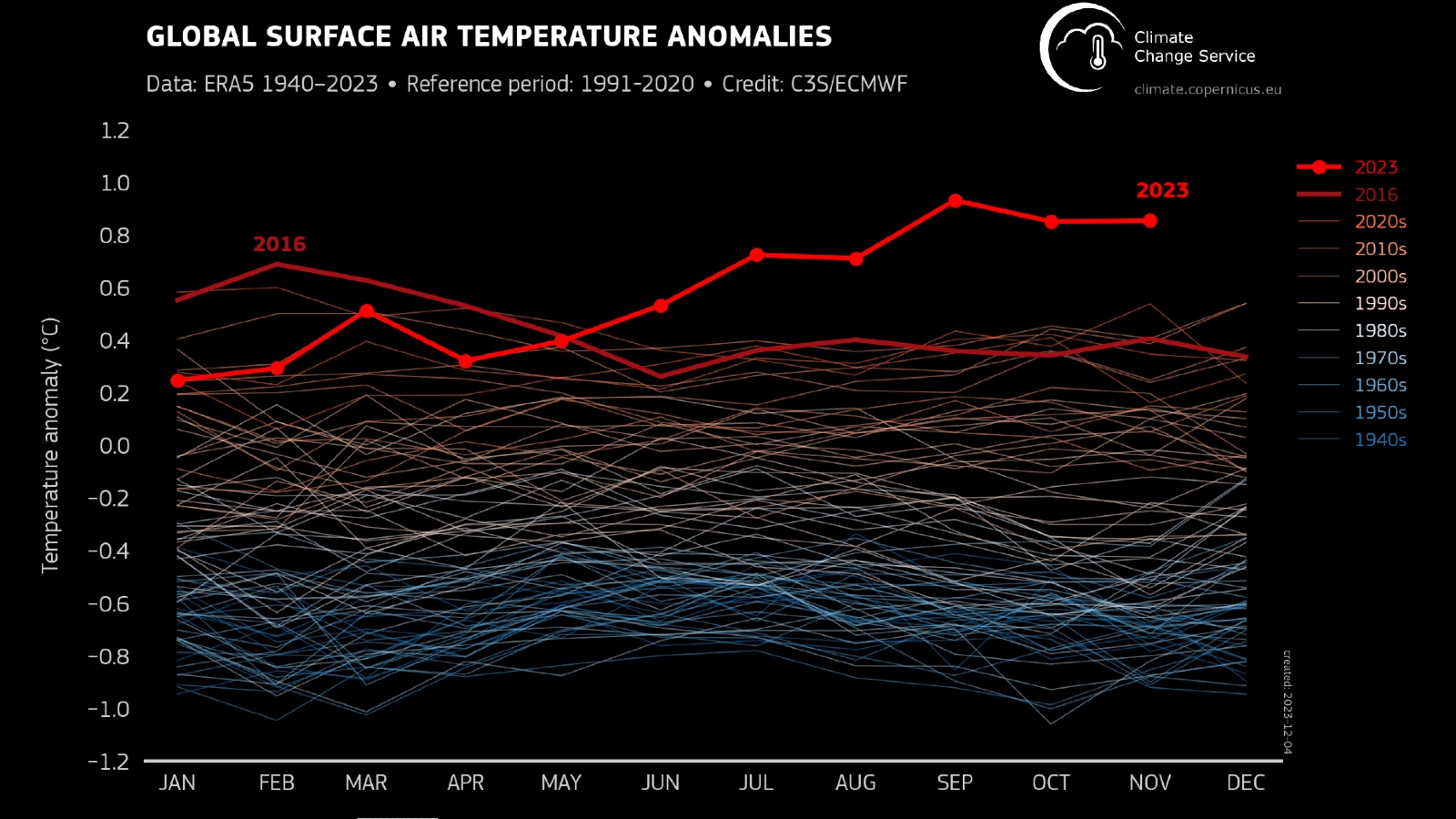

On Dec. 6, the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) — part of the European Union's space program — revealed that this year's boreal autumn, or September to November in the Northern Hemisphere, has been the warmest since their records began in 1940, with temperatures reaching 0.6 degrees Fahrenheit (0.32 degrees Celsius) higher than ever before.

This year, we have already had the warmest summer on record, partly due to a record-shattering heatwave that included a sequence of three of the hottest-ever days globally. During 2023, six individual months also broke their global temperature records, according to C3S, and Antarctica's sea ice reached its lowest levels since records began.

So far this year, average global temperatures have been 2.6 F (1.46 C) higher than temperatures in preindustrial times and 0.2 F (0.13 C) higher than January to November in 2016, which is the current hottest year on record, according to C3S.

These "extraordinary" temperatures mean that 2023 will be "the warmest year in recorded history," C3S deputy director Samantha Burgess said in a statement.

Related: 15 unexpected effects of climate change

The researchers note that the unusually warm boreal autumn was partly caused by the latest El Niño event — a phenomenon where warmer water near the equator triggers warmer global air temperatures — that officially began in June. El Niño will continue into next year, which means that 2024 will likely be just as warm as 2023.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For the last three years, global temperatures were kept in check by a triple-dip La Niña event, which has the opposite effects to El Niño. But without La Niña, sea surface temperatures have climbed higher than ever before.

Some other experts have suggested that the January 2022 eruption of Tonga's underwater volcano, which pumped record levels of water vapor into the atmosphere, may be partly responsible for this year's record heat by trapping more heat in the atmosphere. However, these claims have been largely debunked by researchers.

Despite these factors, the major cause of climbing temperatures is global warming caused by runaway greenhouse gas emissions, which have trapped more than 25 billion atomic bombs' worth of energy in our atmosphere over the last 50 years, the researchers wrote. This excess energy has not only caused air temperatures to skyrocket but also makes extreme events such as El Niño much more unpredictable and potentially damaging, they said.

And the problem is getting worse. On Dec. 4, scientists at the United Nations Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP28) announced that global carbon emissions reached a new high this year.

"As long as greenhouse gas concentrations keep rising we can't expect different outcomes from those seen this year," C3S director Carlo Buontempo said in the statement.

The effects of global warming are becoming more obvious. In 2023, research revealed that climate change is causing major U.S. cities to sink and more than half of the world's largest lakes and reservoirs to shrink. Studies also predicted that the Gulf Stream, which plays a vital role in ocean circulation, could collapse by as early as 2025, and that rising sea levels could swamp the U.S. coastline by 2050.

However, scientists say that we still have time to prevent further disaster.

Leading climate change expert Michael Mann, director of the Center for Science, Sustainability and the Media at the University of Pennsylvania, recently wrote in an opinion piece for Live Science that "we can still stop the worst effects of climate change" if we stop emitting greenhouse gases as soon as possible.

There is still time to preserve what we have now, Mann wrote. "But the window of opportunity is narrowing."

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.