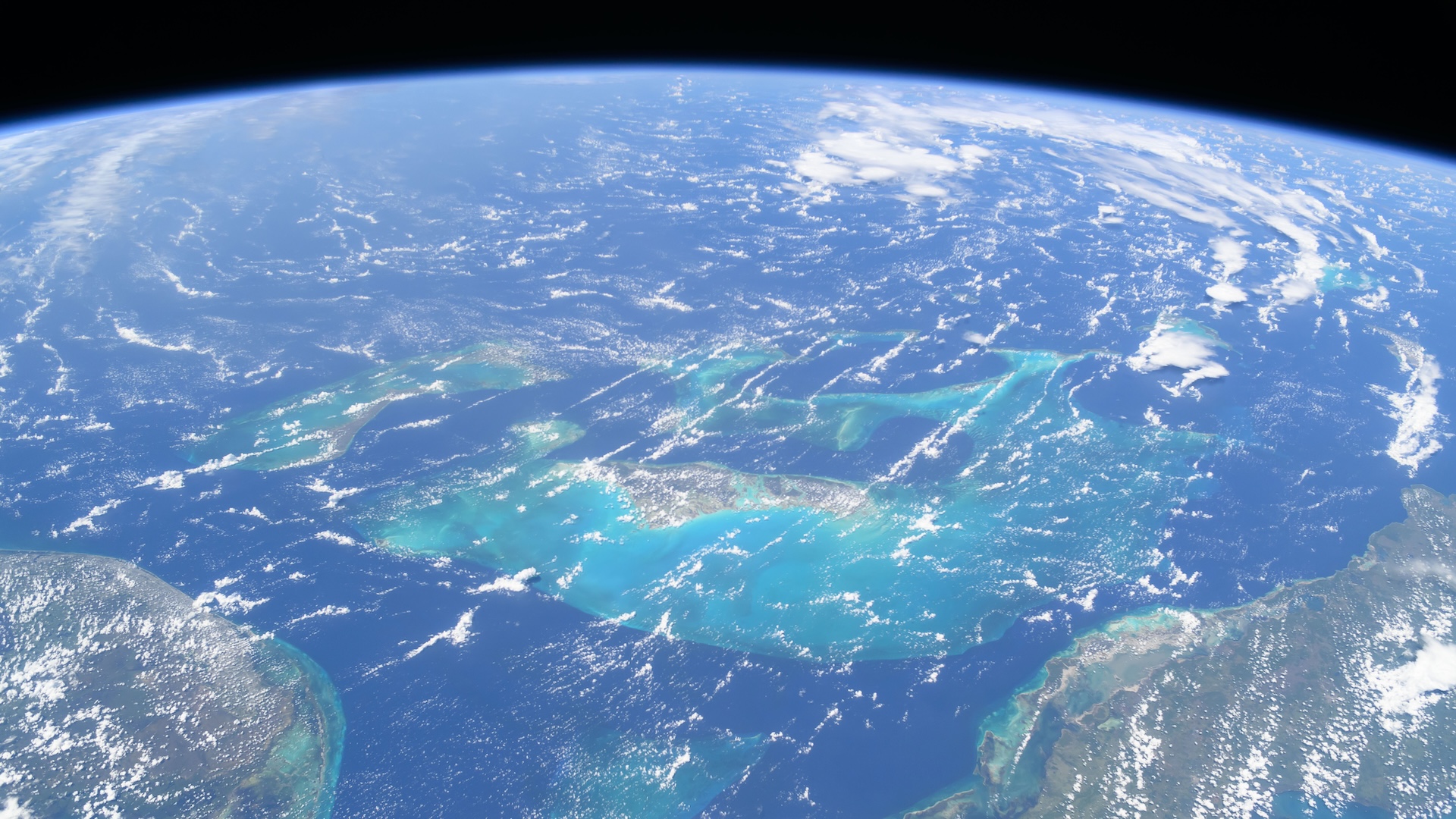

Large patch of the Atlantic Ocean near the equator has been cooling at record speeds — and scientists can't figure out why

Scientists are trying to decipher what drove the recent dramatic cooling of the tropical Atlantic, but so far few clues have emerged. "We are still scratching our heads as to what's actually happening," the researchers said.

For a few months this summer, a large strip of Atlantic Ocean along the equator cooled at record speed. Though the cold patch is now warming its way back to normal, scientists are still baffled by what caused the dramatic cooling in the first place.

The anomalous cold patch, which is confined to a stretch of ocean spanning several degrees north and south of the equator, formed in early June following a monthslong streak of the warmest surface waters in more than 40 years. While that region is known to swing between cold and warm phases every few years, the rate at which it plunged from record high to low this time is "really unprecedented," Franz Tuchen, a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Miami in Florida who is tracking the event, told Live Science.

"We are still scratching our heads as to what's actually happening," Michael McPhaden, a senior scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) who oversees an array of buoys in the tropics that have been gathering real-time data of the cold patch, told Live Science. "It could be some transient feature that has developed from processes that we don't quite understand."

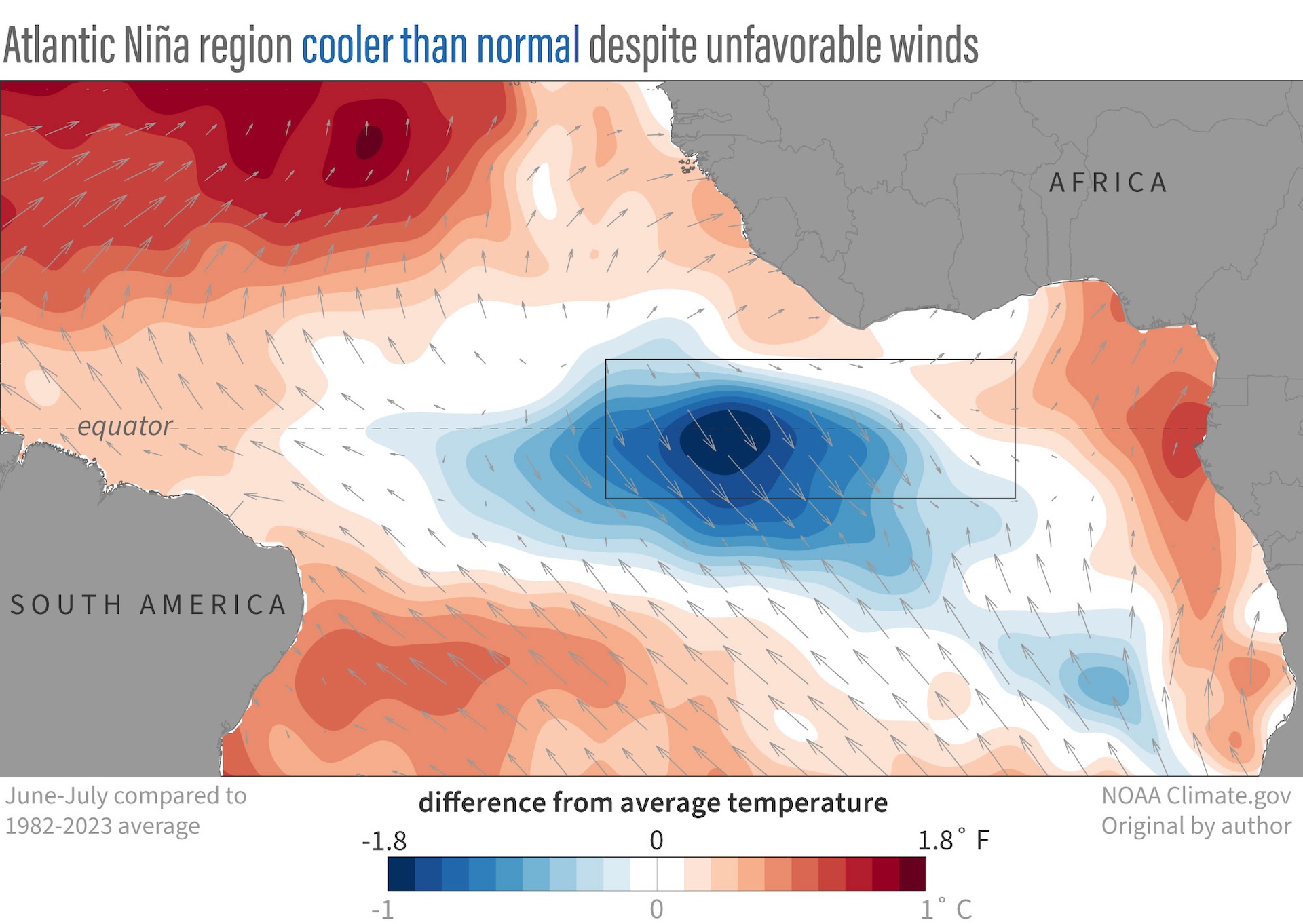

Sea surface temperatures in the eastern equatorial Atlantic were the hottest in February and March, when they exceeded 86 degrees Fahrenheit (30 degrees Celsius) — the warmest months on record since 1982. When June rolled in, temperatures began plummeting mysteriously, reaching their coolest in late July at 77 F (25 C), Tuchen recently wrote in a blog post.

Forecasts showed the cooling event may be on the verge of developing into an Atlantic Niña, a regional climate pattern which tends to increase rainfall over western Africa and decrease rainfall in northeastern Brazil as well as countries hugging the Gulf of Guinea, including Ghana, Nigeria and Cameroon. The phenomenon, which isn't as powerful as the La Niña counterpart in the Pacific, and hasn't occurred since 2013, would have been declared if the colder-than-average temperatures persisted for three months, until the end of August.

Related: Gulf Stream's fate to be decided by climate 'tug-of-war'

However, the cold pocket of water has been warming in recent weeks, so "the verdict is already quite certain that it's not gonna be classified as Atlantic Niña," said Tuchen.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Nevertheless, figuring out just what caused the dramatic cooling would allow scientists to better understand the quirks of Earth's climate, which can eventually benefit weather forecasting, Tuchen said. But none of the expected processes stand out so far.

"Something else going on"

Cooler surface waters are typically accompanied by stronger trade winds, which flow near the equator and are the most influential drivers of Niñas because they sweep away warm surface waters and allow deeper, cooler water to rise through a process known as equatorial upwelling. Puzzlingly, the recent cold region coincides with weaker winds southeast of the equator, which "are doing the opposite of what they should be doing if they were the reason for the cooling," said Tuchen. “At the moment, we believe that the winds are actually responding to the cooling.”

McPhaden noted some anomalously strong winds that had developed to the west of the cold patch in May may have kickstarted the cooling at record speed, but those winds "haven't increased as much as the temperature has dropped," said McPhaden. "There's something else going on."

Scientists have modeled a handful of possible climate processes to try to explain the observed cold region, such as enormously strong heat fluxes in the atmosphere or sudden changes in ocean and wind currents. "From what we see, these are not obvious drivers of this cooling event," said Tuchen.

While unprecedented, the recent dramatic cooling is not likely to be caused by human-driven climate change. "I can't rule it out," said McPhaden. "But at first blush, this is just a natural variation of the climate system over the equatorial Atlantic."

Using data from satellites, oceanic buoys and other meteorological tools, Tuchen and McPhaden are among several climate scientists who are intently tracking the cold patch and any forthcoming effects it would have on the surrounding continents — which could take months to become apparent.

"It's potentially going to be a consequential event," said McPhaden. "We just have to watch and see what happens."

Sharmila Kuthunur is an independent space journalist based in Bengaluru, India. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Science, Astronomy and Space.com, among other publications. She holds a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus