Over half of the world's largest lakes and reservoirs are losing water

The amount lost in the last 30 years is equivalent to 17 Lake Meads — the largest reservoir in the U.S.

Over half of the world’s largest lakes and reservoirs now hold less water than they did three decades ago — and a warming climate and human water consumption are largely to blame, researchers have found.

Lakes and reservoirs store 87% of the liquid fresh water on Earth’s surface. But new research using satellite observations alongside climate data and modeling shows that 53% of Earth’s largest lakes and reservoirs now store significantly less water than they did in 1992. The total amount of water lost is estimated to be 144.5 cubic miles (602.3 cubic kilometers) — equivalent to the volume of 17 Lake Meads, which is the largest reservoir in the U.S.

Only around a quarter of lakes and reservoirs now store more water than in 1992. The researchers also found that a quarter of the world’s population lives within the basins of drying lakes.

Previous research tends to show a pattern of dry regions becoming drier and wet regions becoming wetter, as the effects of climate change become more prominent. But the new study, published 18 May in the journal Science, found that lakes are drying up in the humid tropics as well as in arid regions.

“This suggests that the drying trend worldwide is more extensive than previously thought,” study lead author Fangfang Yao, a climate researcher at the University of Virginia, told Live Science.

Related: Hoover Dam reservoir reaches record-low water levels

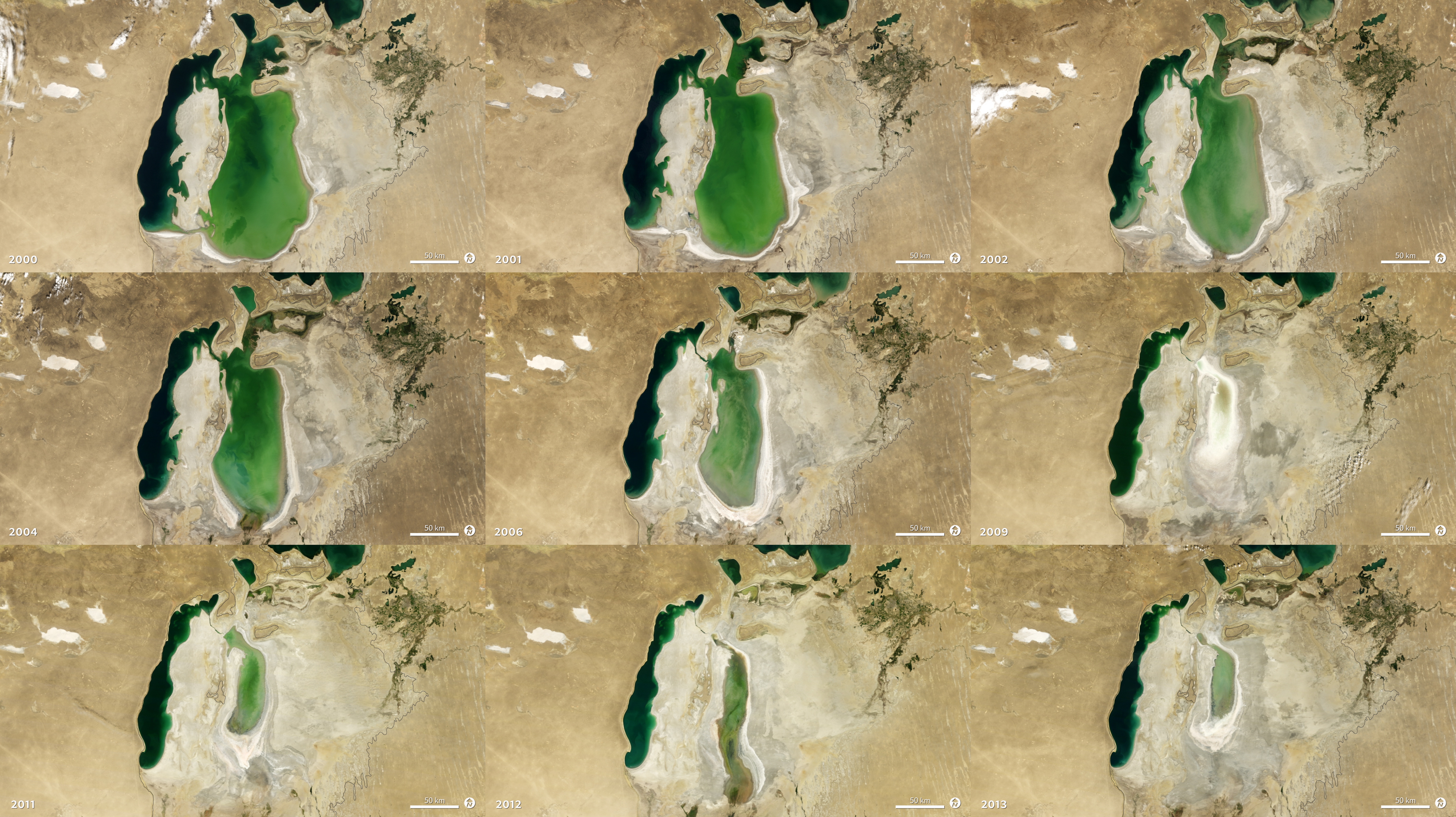

Yao said the study was motivated by the crisis of the Aral Sea in Central Asia, which was the fourth-largest lake in the world before it began drying up in the 1960s. In 2014, NASA released a satellite image showing that the eastern part of the South Aral Sea had completely disappeared.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Less water in lakes means less is available for human consumption — from irrigation and industry uses to domestic drinking water supplies — and low levels can interfere with the production of hydropower. Lake ecosystems also suffer, with fish populations and migrating birds at risk when the water runs low. And when salt lakes dry up, the newly exposed lakebed can become a source of toxic dust storms that degrade nearby soil and cause health problems.

The researchers used a statistical model to work out the main underlying causes of lake and reservoir water loss. Climate warming and human consumption were the main drivers of water loss from lakes, whereas sedimentation — the buildup of debris — was the biggest driver in reservoirs. “Sedimentation is kind of a creeping disaster, since it happens over the course of years and decades,” Yao said.

Whether Earth’s lakes will continue drying depends on the complex interaction of various factors. But this new study can give us some idea of what might happen under various circumstances, Yao said.

The reservoirs that gained water tended to be newly built ones, for example, whereas older reservoirs were more affected by sedimentation — suggesting that those gains in water storage might be short-lived. The lakes that gained water are mostly located in regions with low populations, such as the northern Great Plains in North America, and the researchers found that the gains were mainly driven by increased precipitation.

Yao said that if precipitation levels stay the same, the impact from warming and human water consumption could become problematic. “If we continue [with] business as usual and withdraw the water … to meet our maximum needs, we’ll make the situation worse,” he said.

The study also shows that by changing how we consume water, we can reverse some of the lake shrinkage. Lake Sevan in Armenia, for example, gained water after the government enacted laws to restore the lake and conserve water in the 2000s. “If we take tiny actions on saving the water bodies that are strongly impacted by human activities, these water bodies can be saved,” says Yao.

Kelly Oakes is a freelance journalist covering science, health, environment and technology. Her work has been published by New Scientist, BBC Future, The Observer, Wired UK, and more. Previously, she was Science Editor at BuzzFeed UK. Kelly has a degree in physics and a master’s degree in science communication, both from Imperial College London.