The most important and shocking climate stories of 2024

Soaring carbon emissions, an unexpected new source of global warming, and collapsing ocean currents shocked scientists in 2024. Here are our picks for this year's top climate change stories.

This year, Earth sent clear signals that its climate is warming and tipping into unknown territory.

From a deadly sea of mud that flooded Spain to major hurricanes that smashed one after another into Florida's coast, extreme weather marked 2024. Climate scientists repeatedly warned policymakers that unless countries slash carbon emissions immediately, the planet will enter an even more uncontrollable phase of warming and climate chaos.

But this year wasn't all doom and gloom, because researchers also came up with mitigation strategies to prevent the worst effects of climate change. For example, scientists suggested dehydrating the stratosphere, the layer of Earth's atmosphere that sits between 7.5 and 31 miles (12 to 50 kilometers) above the planet's surface. Scientists think the stratosphere acts like a sponge and prevents heat from escaping into space, so dehydrating it should, theoretically at least, help cool the globe.

From surprising new sources of global warming to a "regime shift" in Antarctica that could spell trouble for the world's oceans, here are our picks for the top climate change stories of 2024.

AI found climate change is making Earth wobble and spin more slowly

This summer, based on artificial intelligence (AI) data, researchers warned that climate change could alter Earth's spin and lengthen our days. Rapidly melting ice in the polar regions means water is accumulating in the ocean, particularly around the equator, causing the planet to bulge around the middle. This could slow Earth's spin as more weight is distributed farther from the planet's center — similar to how a spinning figure skater can slow down by stretching their arms out. Water accumulating near the equator is also moving Earth's axis of rotation and causing the magnetic poles to wobble farther from the axis every year, the researchers found.

A change in Earth's spin means days could get a tiny bit longer. Humans can easily compensate for this change by introducing negative leap seconds. But if the effects get stronger, some experts say it will affect space travel and might even mess with the timekeeping on computers and smartphones.

Earth consistently surpassed 1.5 C of warming

An analysis published in July showed that Earth registered temperatures at least 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit (1.5 degrees Celsius) higher than preindustrial averages for 13 consecutive months starting in June 2023. Every month was hotter than the previous one, suggesting the world is consistently surpassing the 1.5 C warming target set in the Paris Agreement. The global average temperature in those 13 months was 3 F (1.64 C) greater than it was before the industrial revolution, breaking records "like never before," scientists said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

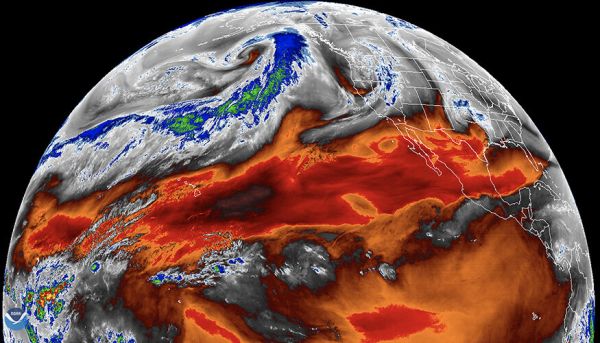

The hot-temperature streak was driven partly by El Niño, a climate cycle that leads to above-average sea temperatures across the east and central equatorial Pacific. But the main culprit was climate change and growing greenhouse gas emissions, the team emphasized. The 1.5 C Paris Agreement pledge is not broken yet, since that target is measured over a period of 20 to 30 years, but there is no sign of temperatures dropping anytime soon, the researchers said.

Scientists found an unexpected new source of global warming

Research published in May found that recent cuts in emissions from shipping have accidentally accelerated global warming and contributed to record-high sea temperatures. Shipping regulations implemented in 2020 slashed the industry's sulfur dioxide emissions by a dramatic 80%. Although this was excellent news for air quality, the rapid cuts went hand in hand with a reduction in sulfur particles, which are highly reflective and bounce the sun's rays back into space, thereby cooling the planet.

Although the new regulations reduced deadly pollution, they also created a giant, unintended geoengineering experiment. Until recently, sulfur particles from shipping had a cooling effect that had offset some of the warming from greenhouse gas emissions. But this year, researchers said the reduction in particles could make the next few years unusually warm. Already in 2023, the magnitude of warming was equivalent to 80% of the increase in Earth's heat uptake in 2020, they said.

Researchers claimed Earth could hit 2 C warming by 2030

A controversial study published in February found that global warming is at least a decade farther ahead than scientists thought, with Earth on track to hit 2 C (3.6 F) of warming relative to preindustrial times by 2030. Previous predictions estimated this level of warming would occur between 2040 and 2050, depending on the extent of cuts to greenhouse gas emissions.

Researchers analyzed the skeletons of sponges in the Caribbean Sea to come to their conclusion. The study assumed that the warming trend inscribed in these skeletons scaled with temperatures across the entire globe. But other experts criticized the findings, arguing that the world's oceans are far from uniform and that warming in the Caribbean Sea is not representative of global trends.

"The extrapolation from that little piece of ocean to the global is wholly unbelievable," Jochem Marotzke, a professor of climate science and the director of the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology in Germany, told Live Science when the study came out.

The study's conclusions were questionable, but there is no doubt that Earth will eventually hit 2 C warming if countries fail to slash emissions. In that sense, the study still contributes to the available climate information, experts told Live Science.

Scientists sounded the alarm bell about Atlantic Ocean currents

This year, climate experts repeatedly warned that key Atlantic Ocean currents could collapse by the end of this century, throwing the Northern Hemisphere, the Amazon rainforest and tropical monsoon regions into climate chaos. Scientists have been raising the alarm about these currents for years, but several studies published in 2024 showed that a collapse would have catastrophic, long-lasting and potentially irreversible impacts. In October, 44 eminent climate scientists wrote an open letter to policymakers, urging them to heed these warnings and cut emissions before it is too late.

The currents in question are those that form the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), a giant ocean conveyor belt that loops around the Atlantic Ocean and includes the Gulf Stream. The AMOC transports heat to the Northern Hemisphere and pumps oxygen into the deep sea, maintaining the temperate climate in Europe and supporting vital ecosystems and fisheries across the Atlantic.

But all of this could soon stop due to climate change. Melting Arctic ice sheets are diluting North Atlantic waters that usually sink to the bottom of the ocean, powering the AMOC's return to the Southern Hemisphere. Without this engine, Northern Europe could experience significant cooling, which is already evidenced by an unusually "cold blob" in the North Atlantic.

Early research indicated that an AMOC collapse was unlikely this century, but now, scientists "don't really consider it a low probability anymore," Stefan Rahmstorf, an oceanographer at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany who organized the open letter, told Live Science in an interview. "That was the reason why we wrote the letter," Rahmstorf said.

Global carbon emissions reached all-time highs

Global carbon emissions from fossil fuels hit a record high in 2024, with 41.2 billion tons (37.4 billion metric tons) of carbon dioxide (CO2) entering Earth's atmosphere. This was a 0.8% increase from 2023, but scientists say there's no sign that emissions have peaked yet, meaning figures next year could be even higher.

At the rate seen this year, researchers estimate there is a 50% chance that global warming will consistently exceed the Paris Agreement's 1.5 C warming target in the next six years. Only deep and immediate cuts in greenhouse gas emissions can prevent this from happening, they said.

Antarctic showed a profound ice "regime shift"

On Feb. 20, the extent of sea ice in Antarctica was close to the lowest it's ever been, at 766,400 square miles (1.985 million square kilometers), spelling trouble for Earth's climate. Sea ice shields the continent's increasingly precarious land ice from warming seawater, thus protecting its hanging glaciers and maintaining the frozen expanse's ability to reflect light back into space.

This year's near-record low comes 12 months after the smallest-ever documented extent of sea ice — 737,000 square miles (1.91 million square km) in February 2023. These persistent lows have some scientists worried that Antarctica has entered a "regime shift" from which it may not recover. The continent, which has long acted as the ocean's heartbeat, is now behaving differently and risks approaching tipping points that could throw the entire Southern Ocean into chaos. Scientists say the immediate impacts of declining Antarctic ice are already here, with mass die-offs of emperor penguin chicks and the biggest heat wave ever recorded striking the continent in 2022.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.