Controversial climate change study claims we'll breach 2 C before 2030

If the new study is correct, global warming is at least a decade further ahead than we thought. But other scientists say it is filled with errors and inconsistencies.

A new study has claimed that we may breach the 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) climate change increase threshold by the late 2020s — almost two decades earlier than current projections.

The study, published Feb. 5 in the journal Nature Climate Change, claims global surface temperatures had increased by 1.7 C (3 F) above pre-industrial averages by the year 2020.

However, other scientists have questioned the findings, saying that there are flaws in the work.

Global warming of 2 C is considered an important threshold — warming beyond this greatly increases the likelihood of devastating and irreversible climate breakdown. Under the 2015 Paris Agreement, nearly 200 countries pledged to limit global temperature rises to ideally 1.5C and safely below 2C.

"The big picture is that the global warming clock for emissions reductions to minimize the risk of dangerous climate change has been brought forward by at least a decade," lead author Malcolm McCulloch, a coral reef expert at The University of Western Australia, said at a news conference on Thursday (Feb. 1). "This is a major change to the thinking about global warming."

A huge issue in climate science is where to set the pre-industrial baseline, before fossil fuel burning kickstarted warming. Until the 20th century, ocean temperatures records were a sporadic and non-standardized patchwork of millions of observations collected by sailors to chart courses through seas.

Related: World must act now to defuse 'climate time bomb,' UN scientists warn

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To weed out erroneous past recordings, climate scientists have previously turned to natural records of temperature stored in ocean animals such as coral, in ice and sediment cores or inside tree grains.

However, scientists still have no consensus on the amount of post-industrial warming. A recent analysis using the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) 2023 dataset suggested Earth had warmed by 1.34 C (2.4 F) above the 1850 to 1900 average, while data from the U.K. Met Office placed it at 1.54 C (2.7 F).

Sponge for knowledge

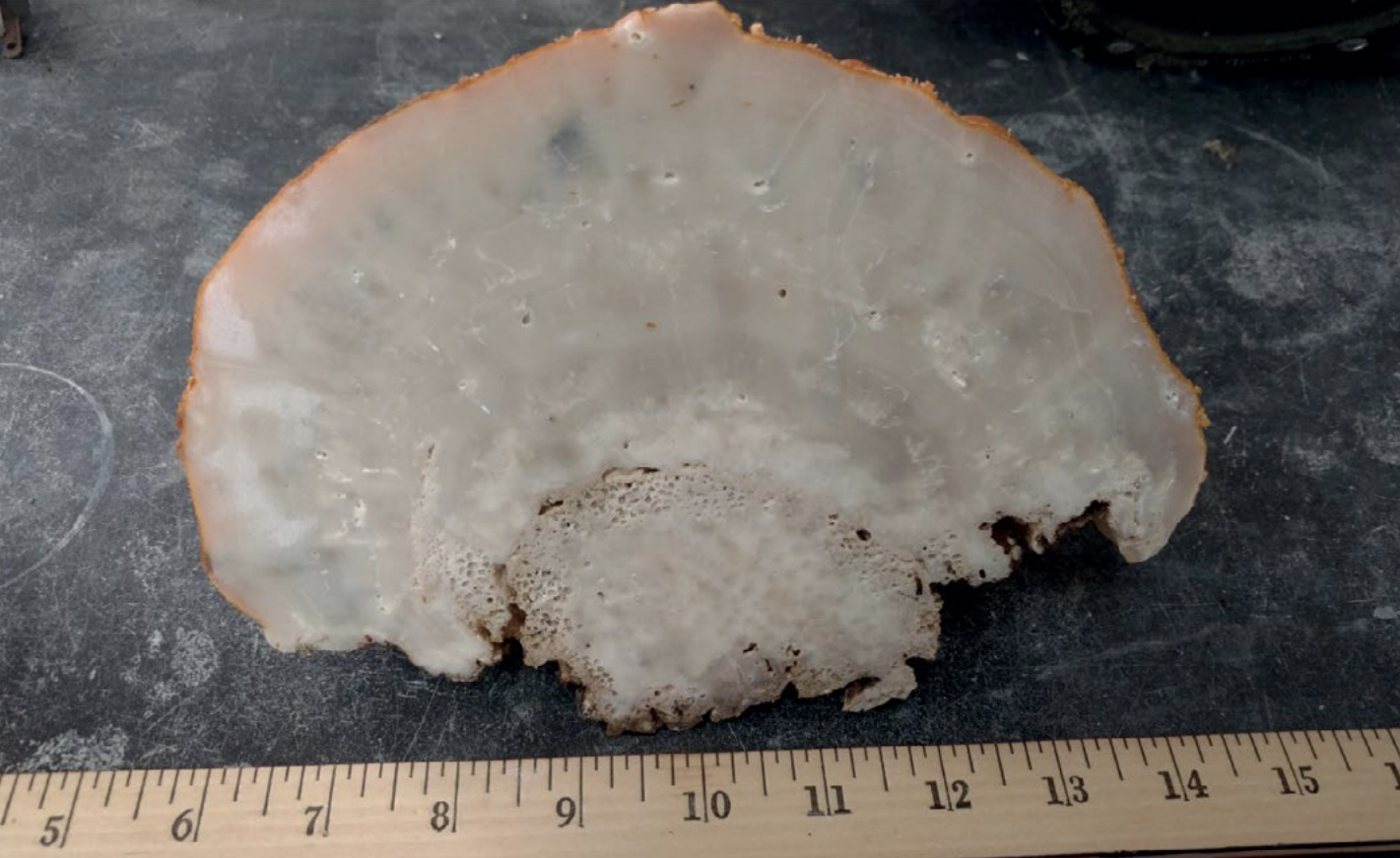

To search for a better record of 19th-century temperatures, the researchers behind the new study looked at a sponge species called Ceratoporella nicholsoni in the Caribbean Sea. Known for their rock-hard exoskeletons, C. nicholsoni can live for more than a thousand years, assiduously adding layers to their limestone shells by drawing strontium and calcium carbonate from seawater.

The ratio of strontium to calcium at a particular part in a sclerosponge's skeleton decreases as ocean waters warm, enabling the scientists to measure 300 years of temperature records in cross-sections of their bodies — similar to reading tree rings.

After collecting and analyzing multiple sponges from depths between 100 to 300 feet (30 to 90 meters), the researchers produced a record of temperatures they say scales with temperatures across the entire planet’s oceans.

Their results suggest that warming began in the 1860s, about four decades earlier than the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimates.

By 1990, they found, global temperatures had increased by 0.9 C (1.6 F) compared with before their newly defined pre-industrial era. In comparison, the IPCC estimates 0.4 C (0.7 F) of warming by this time.

According to the study, if current rates of heating continue, 2 C warming will be reached by the end of the 2020s, with 2.5 C (4.5 F) of warming by 2040.

Troubled waters

Other climate scientists have criticized the new study's findings. The researchers say they assumed that oceans are well-mixed and that the water temperatures recorded by the sponges came from depths that mainly respond to heating from the sun.

But others argue that the ocean is still a highly complex engine that is far from uniform in temperature.

"Skepticism is warranted here. In my view it begs credulity to claim that the instrumental record is wrong based on paleosponges from one region of the world," Michael Mann, the director of the Earth System Science Center at the University of Pennsylvania, told Live Science. "It honestly doesn't make any sense to me."

Camille Parmesan, an ecologist at the University of Texas, Austin and a coordinating lead author for the IPCC's 6th Assessment Report, noted that the temperature of one part of the ocean is unlikely to represent ocean temperatures elsewhere. "You cannot extrapolate from the Caribbean to the whole of the world's oceans," Parmesan told Live Science.

And David Thornalley, a professor of ocean and climate science at University College London, also criticized the researchers' decision to calibrate their sponge data with global sea surface temperatures, rather than the sea surface temperatures for the region the sponges came from.

"The study fails to support its global claims with robust evidence, and it fails by a huge margin," Jochem Marotzke, a professor of climate science and the director of the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology in Germany, told Live Science. "The extrapolation from that little piece of ocean to the global is wholly unbelievable." The claim that the Caribbean's temperature increase since the 1860s comes solely from the sun, rather than ocean mixing, also beggars belief, he added.

The researchers, meanwhile, insist that Caribbean sea surface temperatures trends are globally proportional — citing a 2018 paper.

Even if the conclusions of the study are questionable, scientists said the study could still contribute as a piece in the global jigsaw of climatic information, especially as rapid climate change is approaching regardless of the mix of evidence used or where the baseline is set.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.