Defense systems found in all complex life on Earth came from "Asgard."

The ancestor of plants, animals and fungi evolved around 2 billion years ago, likely from a group of complex microbes called Asgard archaea — and we inherited two defense proteins that fight off viruses from those single-cell organisms, new research suggests.

"This study shows that if we want to understand the origins of our immune system, we need to include archaea, especially Asgard archaea, in the discussion," study first author Pedro Lopes Leão, a microbiologist at Radboud University in the Netherlands, told Live Science in an email.

The tree of life is broken up into three domains: Bacteria, Eukarya and Archaea. Bacteria are tiny, simple cells with no nucleus. Eukaryotes, by contrast, keep their DNA in a nucleus and have specialized "organelles," such as mitochondria and ribosomes, each of which performs specific functions. And then there are the microscopic-yet-complex archaea, which lack nuclei and organelles, but use energy in ways similar to eukaryotes.

"These microbes are super interesting because they are more like plants and animals (eukaryotes) than bacteria," senior study author Brett Baker, an associate professor of integrative biology and marine science at the University of Texas at Austin, told Live Science in an email.

Related: Meet LUCA, the 4.2 billion-year-old cell that's the ancestor of all life on Earth today

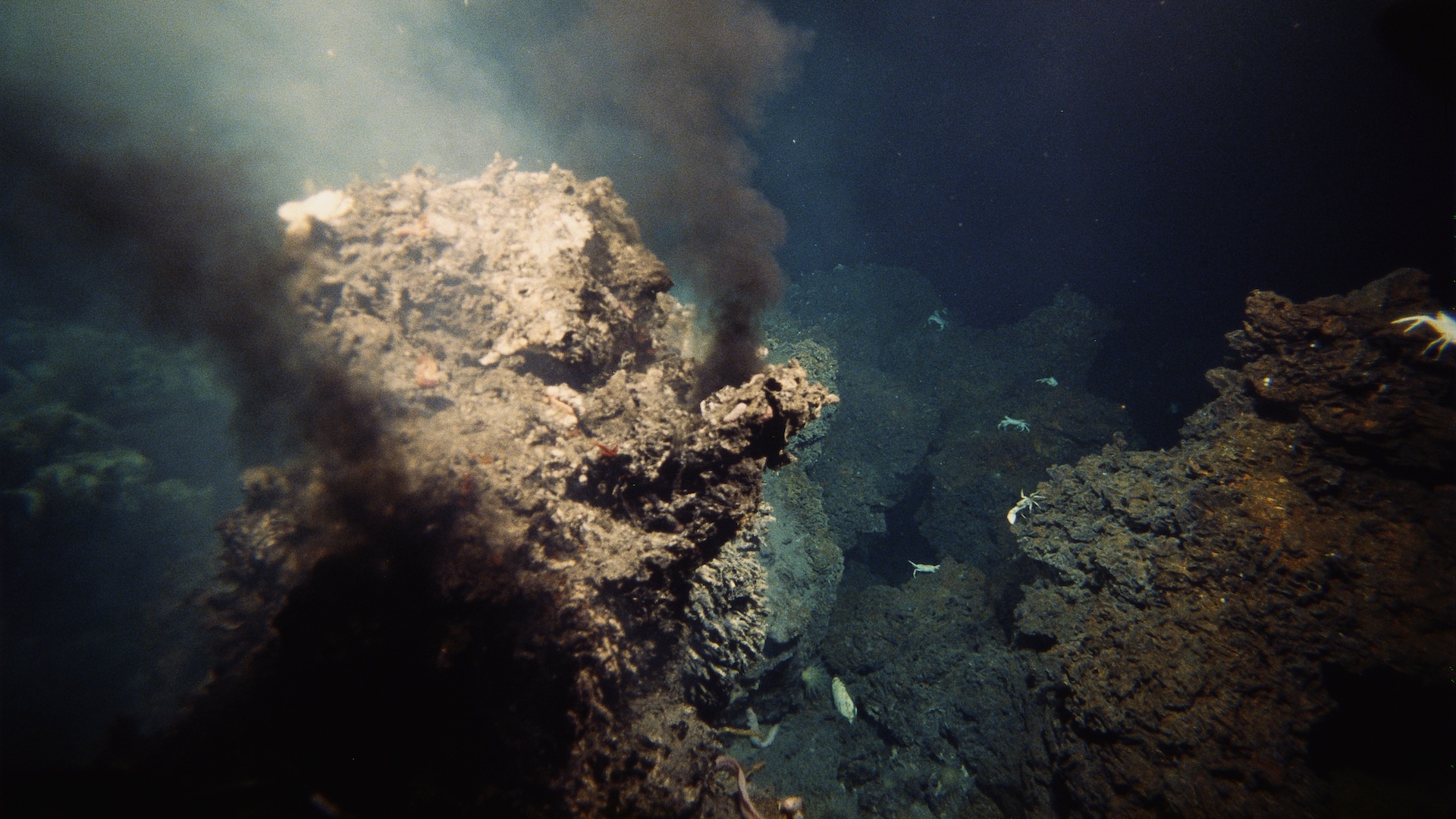

In 2015, scientists first described a newfound superfamily of archaea that bridged the gap between bacteria and eukaryotes. Named Asgard archaea because they were collected from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent in the Arctic known as "Loki's castle," these cells transformed our understanding of the evolution of complex life.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Follow-up research suggested that all eukaryotes evolved from Asgard archaea that lived around 2 billion years ago.

To understand more about how complex life first evolved, Baker's team sifted through thousands of genomes across the tree of life, identifying tens of thousands of "viral defense systems," or genes that code for proteins that fight viruses.

Of these, they zeroed in on genes that code for two classes of proteins: viperins and argonautes, that showed up across every domain of life.

In humans, viperins are part of the body's innate, or first-line, defense system. They were first described in humans and play a role in fighting off a wide array of viruses, from hepatitis C to HIV. They help keep viruses from making copies of viral proteins inside infected cells. Argonautes, on the other hand, were first found in plants that look like little squid, and stop viruses from making copies of themselves by chopping up their genetic material.

The genes for both classes of proteins were found across the huge array of life the team studied. But the genes were much more similar between archaea and eukaryotes than between bacteria and the other two domains.

In particular, the catalytic sites — key parts of the proteins that perform their essential functions — had changed very little over the 2 billion years since eukaryotes first evolved, the researchers reported.

The findings, published in July in the journal Nature Communications, suggest these two types of immune proteins originally came from an ancient Asgardian ancestor.

That the key sites on these proteins have evolved so little over the eons "speaks to the fact that they work well," Baker said.

As follow-up work, the team is looking for other defense systems in these microbes.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.