What is the 'tree of life'?

The tree of life maps out the relationships between all living things, and it's in constant flux.

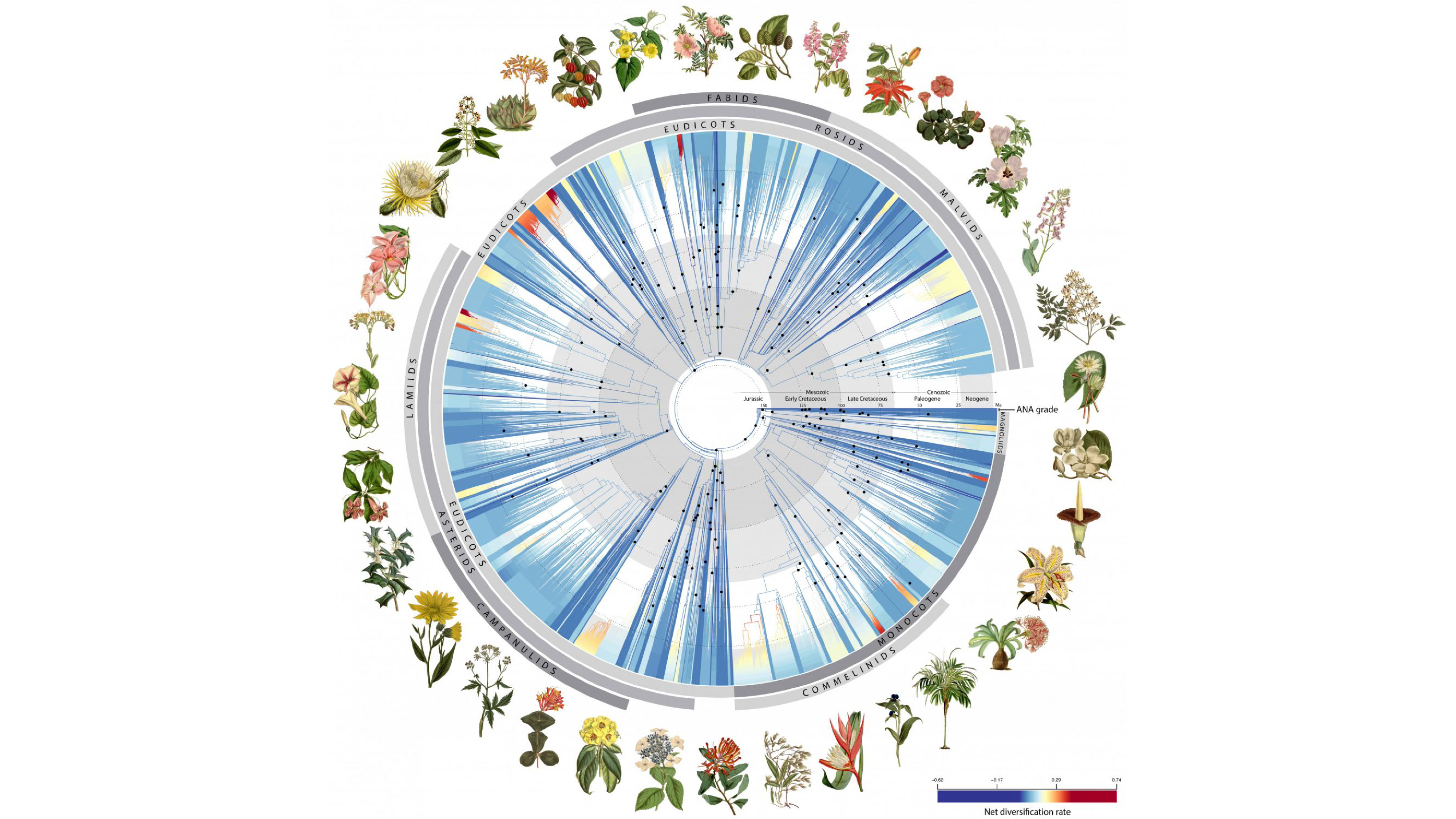

All species on Earth, both living and extinct, are related. We know this because of a biological tool called the tree of life. This "tree" takes the form of a diagram that maps the relationships between plants, animals and other organisms. Its "trunk" successively forks into millions of ever-more intricate "branches," each of which represents a new strand of life.

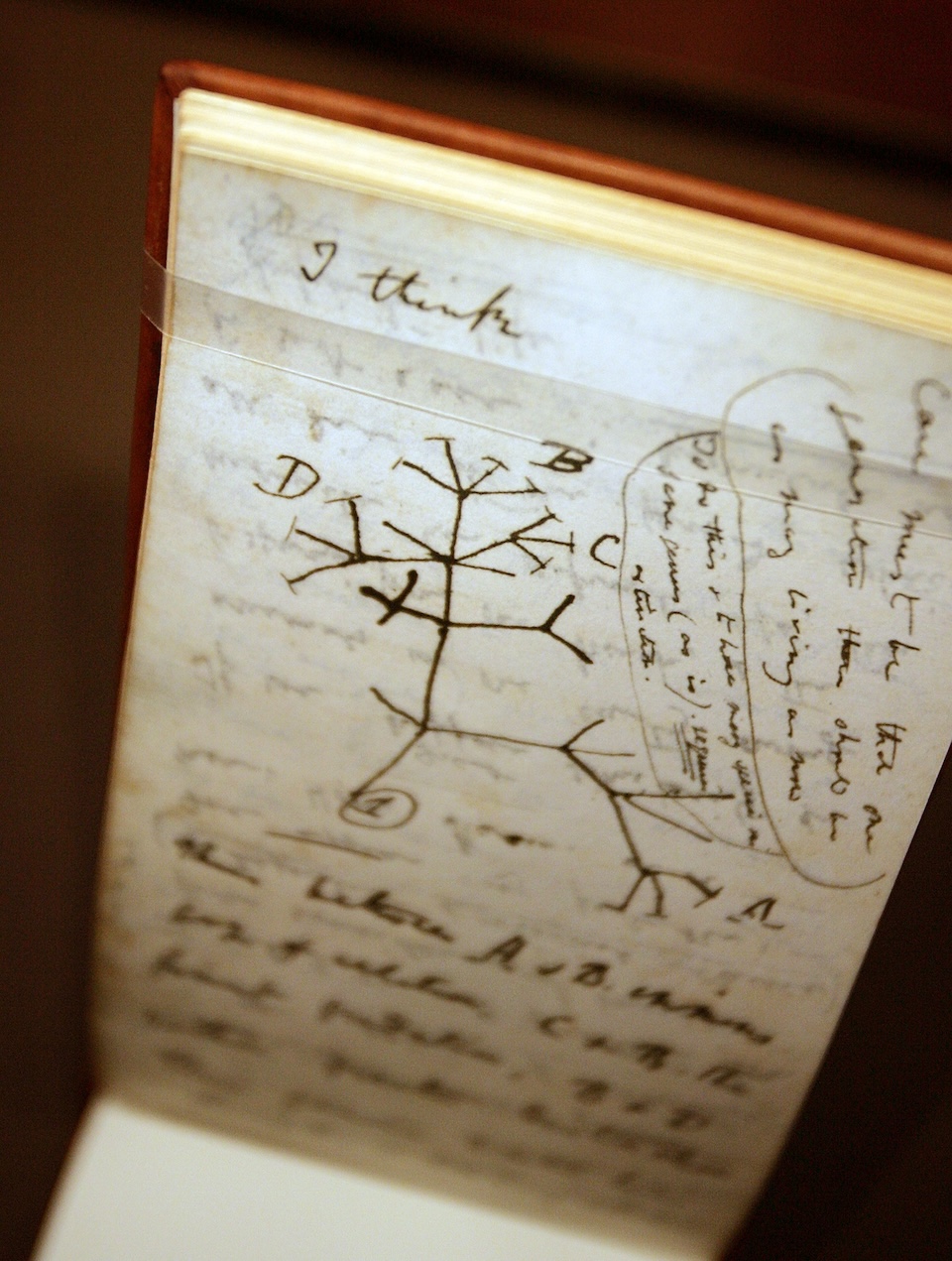

The origins of this biological metaphor are difficult to trace, because scientists throughout history have tried to visually depict the relationships among organisms in tree-style diagrams. But most scientists credit the modern inception of the tree to Charles Darwin.

"'The really big thing with Darwin is that he has a mechanism by which the different branches actually occur," said Ian Barnes, a molecular evolutionary biologist at the Natural History Museum in the United Kingdom. That mechanism, of course, is evolution, Barnes told Live Science.

Related: Charles Darwin's stolen 'tree of life' notebooks returned after 20 years

According to Darwin, all life on earth originated from a single ancestor: in future decades, research would go on to show that there was likely a "last universal common ancestor" (LUCA) — a cell that existed about 4.2 billion years ago, from which all life on Earth evolved. Today, LUCA represents the thick base of the tree, and from this foundation, the tree parts into three sturdy branches. "Your first starting groups would be Bacteria, Eukarya and Archaea," Barnes said — the three primary domains of life.

If we trace from the finer twigs back to the thicker branches of the tree, it shows us how all life on Earth is connected and how close or distant those relationships are, Barnes explained. The fewer the branches between two species, the more closely they are related.

However, "the tree is not an immutable, static thing," Barnes added. Historically, scientists based the tree of life on painstaking observations of the physical differences between living things because it was the only tool they had to determine how closely related organisms were. But now, we have DNA analysis, which can reveal how much genetic material two organisms have in common and, therefore, in many cases it can show more conclusively how close their relationship is.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Each branch on the tree signifies the splitting of a common ancestor into two or more descendants — a process powered by natural selection. Take Eukarya, for example. This huge branch includes all multicellular life. Over the course of millions of years, it splits into distinct evolutionary lineages known as clades. A clade encompasses an ancestor and all descendants that spring from it.

Eukarya includes three familiar clades: plants, fungi and animals. Following the animal clade, which is defined as a "kingdom," there is a point in the tree where two new clades form from the divergence of animals into invertebrates (those without a spinal column) and vertebrates (those with a spinal column). The group Vertebrata then branches into several clades of its own, including mammals. From this class, through successive branching over millions of years, our species, Homo sapiens, eventually emerged.

In fact, DNA analysis has shown that the foundational relationships that were historically represented on the tree are surprisingly accurate. But our modern tools have also redrawn connections on some branches. "Even now if we generate more DNA sequence data, or we analyze it in a different way, we are changing the relationships on the tree," Barnes said.

Despite these continuous changes, the tree of life remains a highly useful tool, he added. By revealing relationships among species, the tree of life has helped scientists identify new candidates for pharmaceutical treatments, for instance. Looking at the tree can also reveal how life has ebbed and flowed over time, as well as allow us to compare historical extinction rates with those today and understand their drivers, Barnes said.

"It's not just a cartoon of the relationships between organisms, which would be pretty useful in itself," he added. “But particularly once we can put a timescale onto things, it actually becomes an analytical tool."

Emma Bryce is a London-based freelance journalist who writes primarily about the environment, conservation and climate change. She has written for The Guardian, Wired Magazine, TED Ed, Anthropocene, China Dialogue, and Yale e360 among others, and has masters degree in science, health, and environmental reporting from New York University. Emma has been awarded reporting grants from the European Journalism Centre, and in 2016 received an International Reporting Project fellowship to attend the COP22 climate conference in Morocco.