'Another piece of the puzzle': Antarctica's 1st-ever amber fossil sheds light on dinosaur-era rainforest that covered South Pole 90 million years ago

Until now, Antarctica was the only continent on Earth without any known amber fossils. But sediment cores taken from below the seafloor have revealed a tiny piece of fossilized resin holding fragments of an ancient rainforest that covered the South Pole during the Cretaceous period.

For the first time, researchers have discovered a piece of fossilized resin, or amber, in Antarctica. The tiny golden fragment, unearthed beneath the seafloor, contains microscopic remnants of an ancient dinosaur-era rainforest that sprawled across the continent 90 million years ago, a new study reveals.

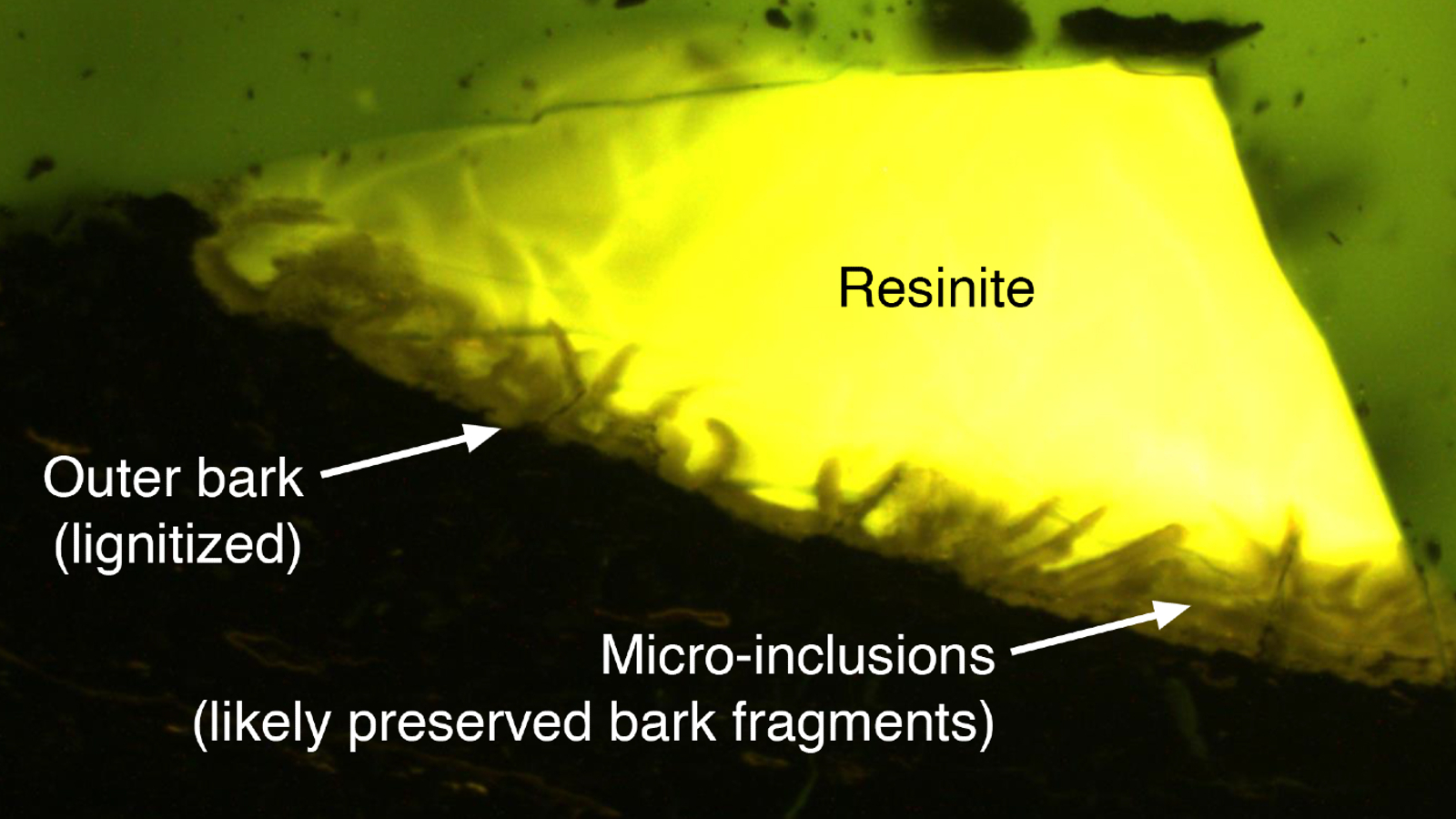

Amber is fossilized resin, or tree sap, that can trap plants, insects, small animals or other organic matter with it as it hardens. The golden-yellow casing is airtight and mostly see-through, meaning it both perfectly preserves and displays whatever is inside it, like a transparent time capsule.

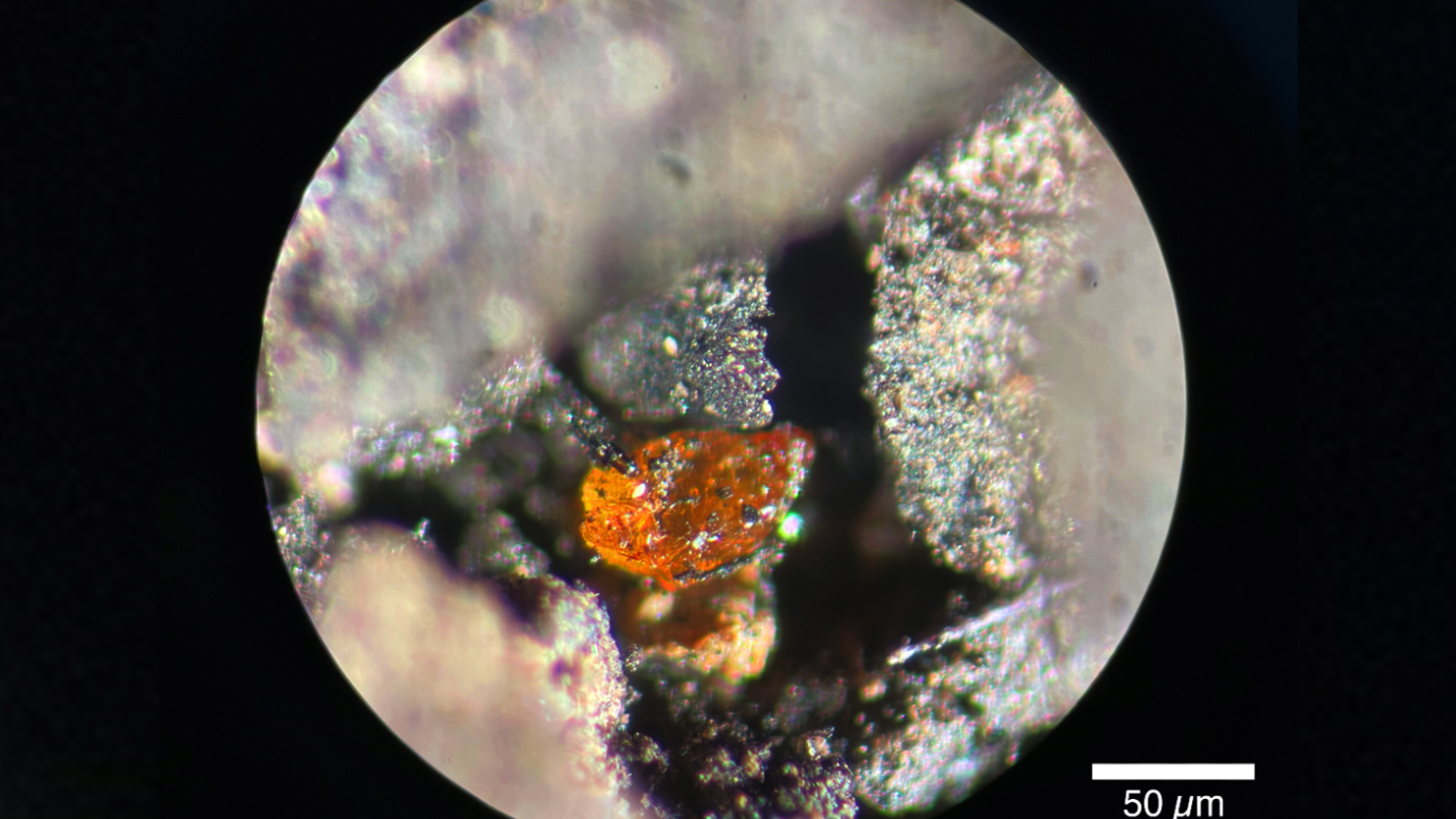

Until now, amber fossils had been found on every one of Earth's continents, except for Antarctica. But in the new study, published Tuesday (Nov. 12) in the journal Antarctic Science, researchers identified a tiny piece of amber, around 0.002 inch (70 micrometers) across, in sediment cores collected beneath the seafloor at a depth of around 3,100 feet (950 meters) off the coast of Pine Island Glacier on Antarctica's west coast.

The tiny fragment dates back to around 90 million years ago during the Cretaceous period (145 million to 66 million years ago). At this time, large parts of Antarctica were covered by a temperate rainforest, similar to those found in New Zealand today, that thrived in warmer climatic conditions — and a tiny part of that lost ecosystem is trapped within the amber.

"This discovery allows a journey to the past in yet another more direct way," study lead author Johann Klages, a sedimentologist at the Alfred Wegener Institute in Germany, said in a statement. "Our goal now is to learn more about the forest ecosystem."

Related: Wildfires burned Antarctica 75 million years ago, charcoal remnants reveal

The sediment cores used in the study were first collected in 2017 and were later revealed to contain fossils of roots, pollen, spores and other remains from flowering plants, which represent some of the best evidence of Antarctica's Cretaceous-era rainforest.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The amber fragment was only recently discovered as researchers broke up the remaining materials into thousands of tiny pieces and painstakingly scanned each one using fluorescent microscopy. Further analysis revealed that it contained "micro-inclusions" from bark that would have likely once lined a conifer-like tree that lived in the ancient forest.

The bark also shows some signs of "pathological resin flow" — a strategy used by trees to seal up damage done to their woody shielding by parasites or wildfires, by creating a chemical and physical barrier with resin.

While the new fragment is small, it is unusually well-preserved despite it being buried under the seafloor.

"Considering its solid, transparent and translucent particles, the amber is of high quality," study co-author Henny Gerschel, a consultant at the Saxony State Office for the Environment, Agriculture and Geology in Dresden, Germany, said in the statement. The fragment must have spent most of the last 90 million years near the seafloor's surface, "as amber would [normally] dissipate under increasing thermal stress and burial depth," she added.

The researchers believe that their findings could open the door to finding more Antarctic amber, which could unlock even more secrets about this ancient rainforest and the dinosaurs that lived in it.

"Our discovery is another piece of the puzzle," Gerschel said.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.