Refuge from the worst mass extinction in Earth's history discovered fossilized in China

The End-Permian mass extinction killed an estimated 80% of life on Earth, but new research suggests that plants might have done okay.

The mass extinction that killed 80% of life on Earth 250 million years ago may not have been quite so disastrous for plants, new fossils hint. Scientists have identified a refuge in China where it seems that plants weathered the planet's worst die-off.

The end-Permian mass extinction, also known as the "Great Dying," took place 251.9 million years ago. At that time, the supercontinent Pangea was in the process of breaking up, but all land on Earth was still largely clustered together, with the newly formed continents separated by shallow seas. An enormous eruption from a volcanic system called the Siberian Traps seem to have pushed carbon dioxide levels to extremes: A 2021 study estimated that atmospheric CO2 got as high as 2,500 parts per million (ppm) in this period, compared with current levels of 425 ppm. This caused global warming and ocean acidification, leading to a massive collapse of the ocean ecosystem.

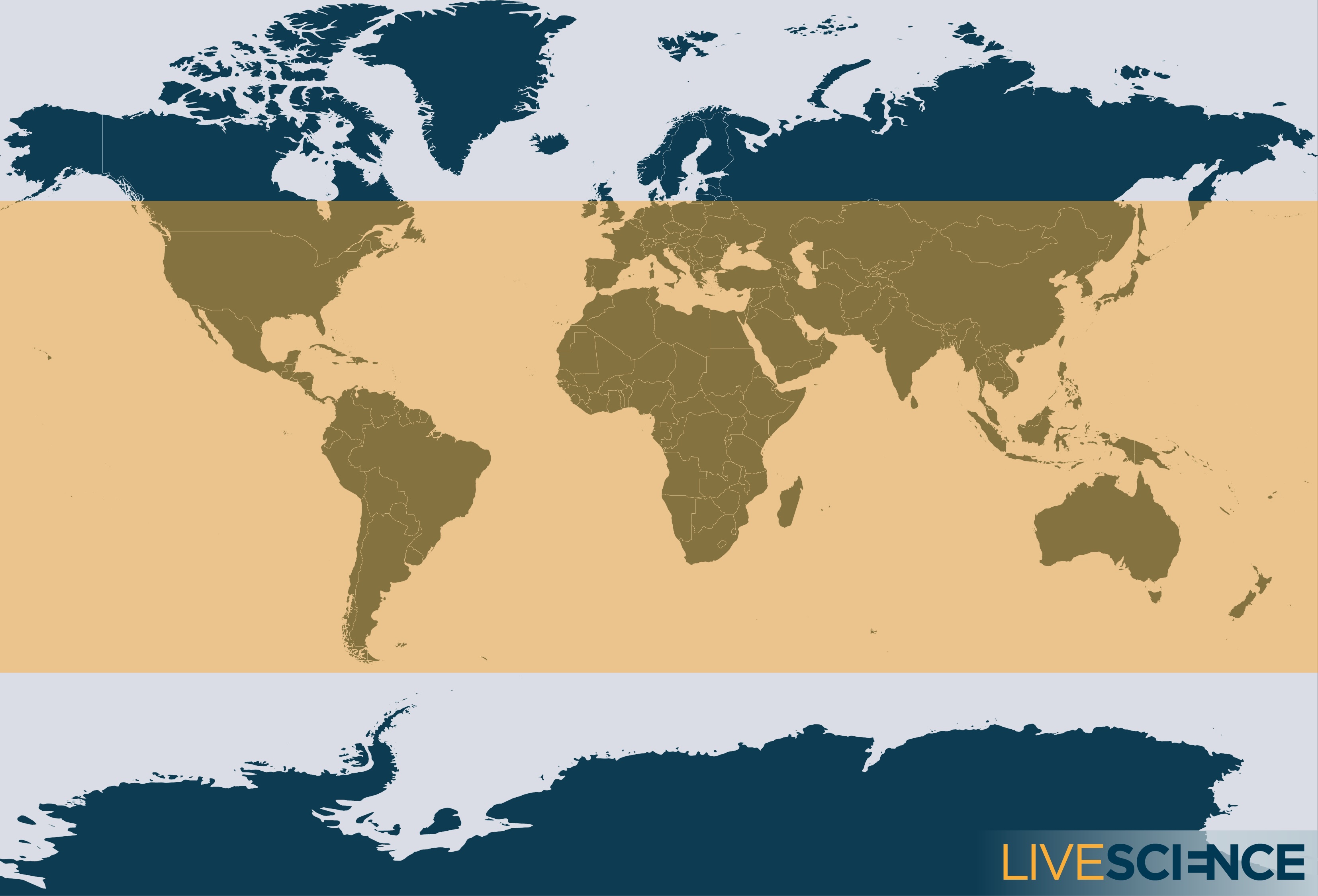

The situation on land is far hazier. Only a handful of places around the world have rock layers containing fossils from land ecosystems at the end of the Permian and beginning of the Triassic.

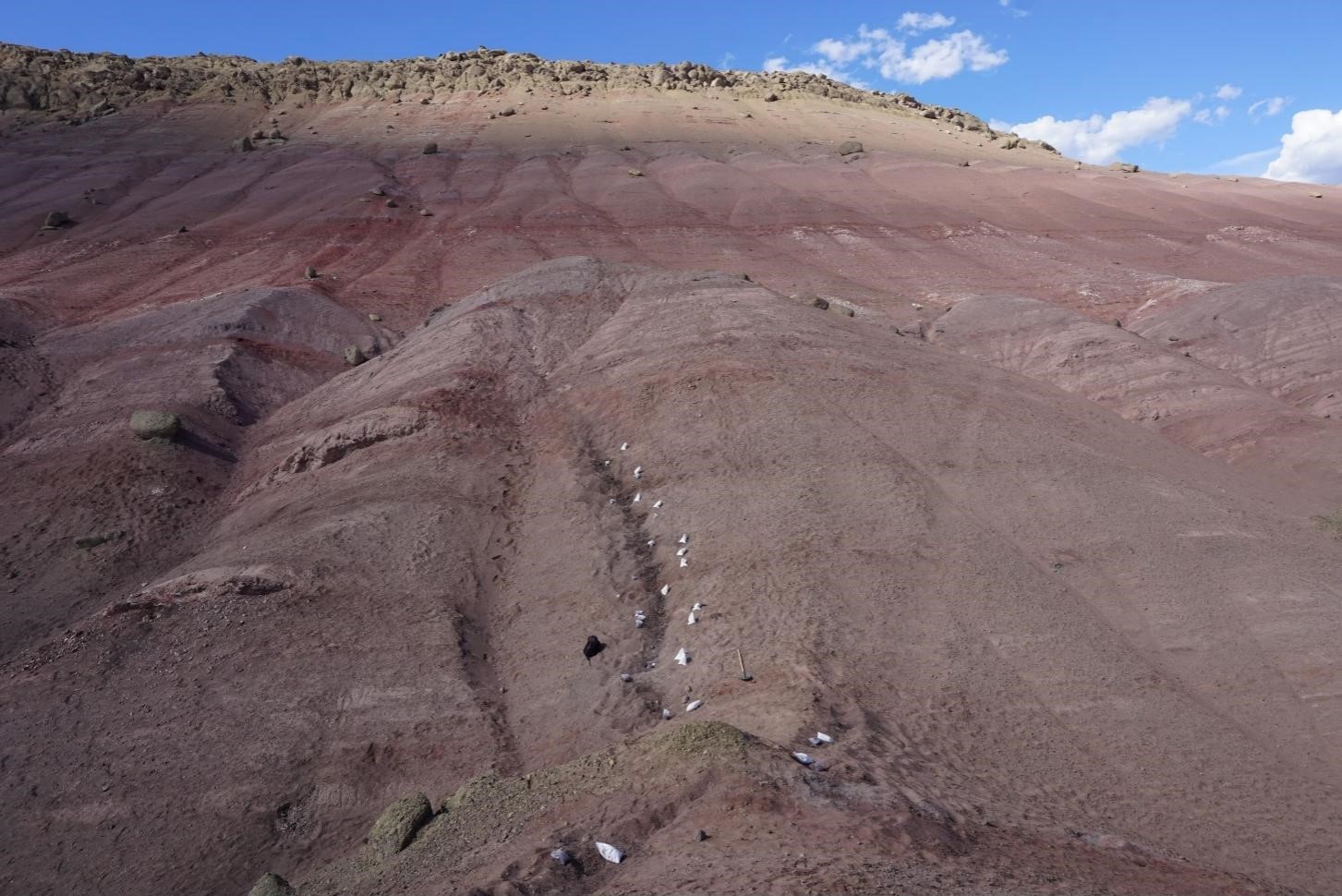

A new study of one of these spots — located in what is now northeastern China —revealed a refuge where the ecosystem remained relatively healthy despite the Great Dying. In this place, seed-producing gymnosperm forests continued to grow, complemented by spore-producing ferns.

"At least in this place, we don't see mass extinction of plants," study co-author Wan Yang, a professor of geology and geophysics at the Missouri University of Science and Technology, told Live Science.

The finding, published Wednesday (March 12) in the journal Science Advances, adds weight to the idea that the Great Dying was more complicated on land than in the seas, Yang said.

The great changover?

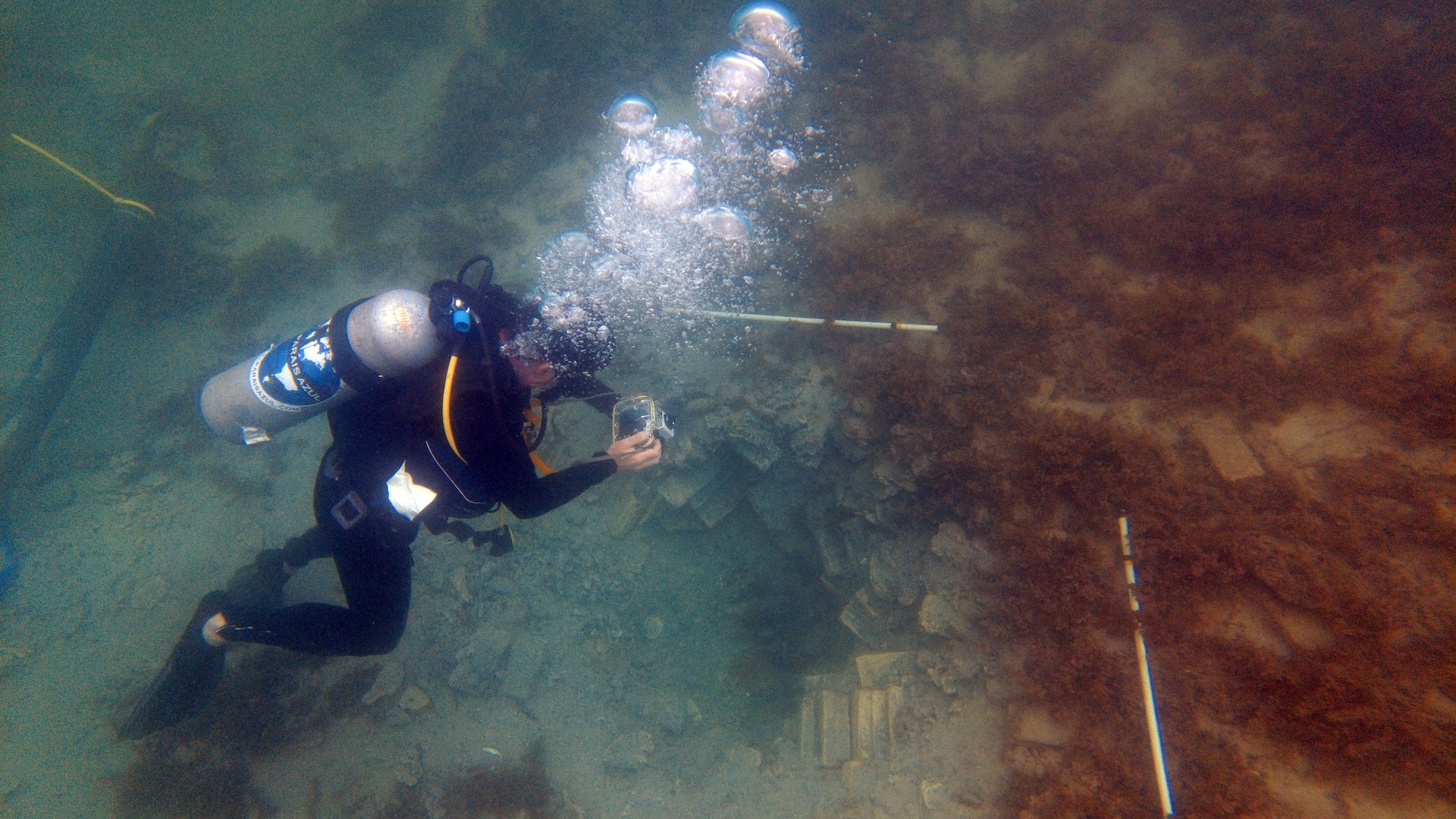

Yang and his colleagues looked at rock layers in Xinjiang that span the mass extinction event.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A major advantage of this now-desert site is that the rocks include layers of ash that hold tiny crystals called zircons. The zircons include radioactive elements — lead and uranium — that gradually decay, which enables researchers to determine how long it has been since the crystals formed. This means the researchers can more accurately date the rock layers here than they can at other sites.

Some of these layers also hold fossil spores and pollen. These fossils reveal that there wasn't a massive die-off and repopulation but a slow changeover of species, Yang said.

This is consistent with other evidence from Africa and Argentina, where plant populations seemed to have shifted gradually rather than dying off dramatically and then repopulating, said Josefina Bodnar, a paleobotanist at the National University of La Plata in Argentina who was not involved in the research.

Land plants "have a lot of adaptations that allow them to survive this extinction," Bodnar told Live Science. "For example, [they have] subterranean structures, roots or stems, that can survive perhaps hundreds of years." Seeds can also persist a long time, she added.

This survival may have been particularly possible at humid, high-latitude regions. The site in Xinjiang was once dotted with lakes and rivers, a few hundred miles from the coast. Other places where plant refuges have been found, such as Argentina, were also high-latitude in the Permian, far from the equator where temperatures were the hottest.

Yang and his colleagues found that during the late Permian and early Triassic, the climate became a bit drier in what is now Xinjiang — but not enough to cause deforestation.

This may have been a consequence of location, said Devin Hoffman, a researcher in paleontology at University College London who was not involved in the new study. Marine animals had no escape from global ocean acidification. But climate change on land wasn't uniform. The impact would have been most pronounced in the center of Pangea, which was a vast desert.

This means that in more temperate regions on land, survival could have been possible, Hoffman told Live Science. "You essentially have everything being pushed toward the poles and towards the coast, but on land you're able to escape some of the effects," he said.

The planet's memory

These findings have led to some debate over whether the greatest mass extinction ever deserves the moniker on land. "I will call it a crisis on land. I will not call it an extinction," said Robert Gastaldo, an emeritus professor of Geology at Colby College who was not involved in the new study, but who has collaborated with Yang in the past.

The end-Permian extinction is particularly interesting to scientists because it was driven by greenhouse gases, much like climate change today. The situation was far more extreme then: The polar ice caps melted completely — a situation that would cause sea levels to rise a staggering 230 feet (70 meters) today.

But humans may be nearly as deadly as giant volcanoes. A 2020 study, for example, found that a smaller extinction event at the end of the Triassic (201 million years ago) was driven by greenhouse gas pulses from volcanoes that were on a similar scale to what humans are expected to emit by the end of this century. Studying these ancient catastrophes can give us a sense of what to expect under atmospheric carbon dioxide levels people have never experienced, Gastaldo said.

"The planet has experienced it," he said. "The planet's memory is in the rock record. And we can learn from the rock record what happens to our planet under these extreme conditions."

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.