Earth from space: Giant, pyramid-like 'star dunes' slowly wander across Moroccan desert

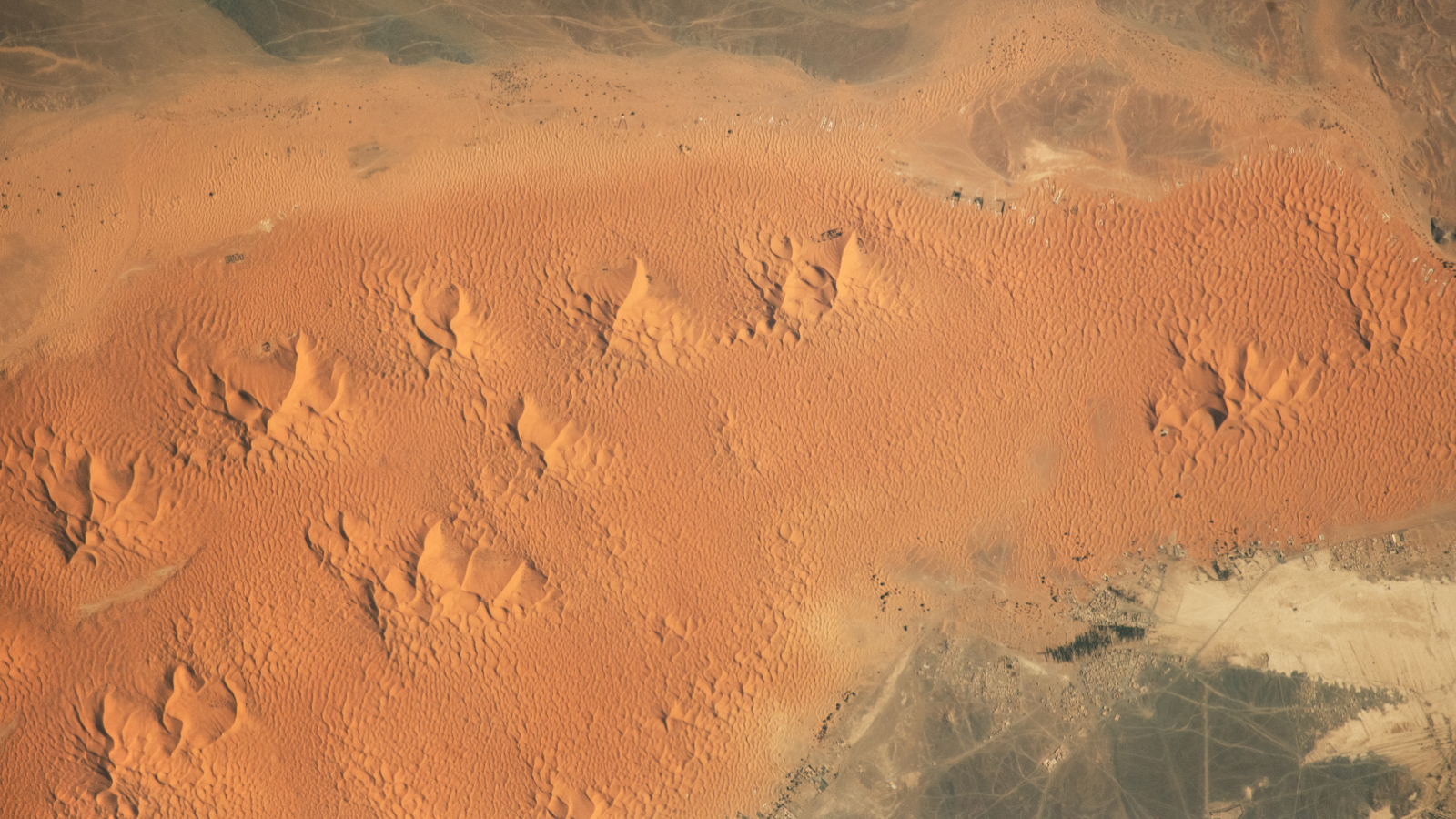

This 2023 astronaut photo shows a series of slowly moving "star dunes" in the Erg Chebbi region of Morocco. Most of these massive structures are likely several centuries old.

Where is it? Erg Chebbi, Morocco [31.07988204, -3.986015555]

What's in the photo? A group of large "star dunes" near the edge of the Sahara desert

Who took the photo? An unnamed astronaut on board the International Space Station

When was it taken? Dec. 21, 2023

This intriguing astronaut photo shows around a dozen giant "star dunes" as they slowly dance across a sandy field near the edge of the Sahara desert. The rare dunes, which are often confused with human-made pyramids, are likely several centuries old, recent research has revealed.

The unusual structures are located in Erg Chebbi. This field of open, windswept sand — or erg — covers around 65 square miles (170 square kilometers) in southwest Morocco along the northwestern edge of the Sahara. The erg is surrounded by flat lowlands but contains some of the tallest dunes in the Sahara, making it stand out like a mountain range when viewed from afar.

The town of Merzouga is also visible in the bottom right of the image. This settlement is built on top of a large aquifer, or underground reservoir, which allows palm groves to flourish alongside the desolate landscape and draws in tourists who are looking to explore the erg's sandy peaks.

A star dune is a type of sand dune that has at least three ridges coming from a central peak, which gives it a star-like shape when viewed from above, according to NASA's Earth Observatory. But when they're viewed from the side, their multiple smooth slopes, known as "slip faces," can make the star dunes look very similar to pyramids from ground level.

These dunes, which can grow to be over 300 feet (90 meters) tall, form only in locations where wind directions change constantly, which allows their different slopes to form, according to the National Park Service. As a result, they move by just a couple of inches every year in the direction of the strongest prevailing wind. That's a lot slower than some other wandering dunes, which can travel up to 1,000 feet (300 m) annually when blown in a single direction.

Related: See all the best images of Earth from space

The largest star dune in Erg Chebbi, Lala Lallia, is 330 feet (100 m) tall and is located slightly to the north (left) of the dunes in the satellite image. In March 2024, researchers revealed that this dune is around 900 years old, which is much younger than previous estimates had suggested.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The same study also revealed that some of the sand buried at the base of this dune is up to 13,000 years old. These grains predate an 8,000-year period of climatic change that occurred after the end of the last ice age. During this time, the Sahara was temporarily transformed into a swampy environment covered in vegetation — a shift that ended only around 4,000 years ago, researchers wrote at the time.

On Earth, star dunes are also found in China, Namibia, Algeria, Saudi Arabia and several U.S. states, including California and Colorado. But very similar structures can be found on Mars, according to NASA.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.