Earth from space: Otherworldly stripes and shadowy dunes share center stage in 'hottest place on Earth'

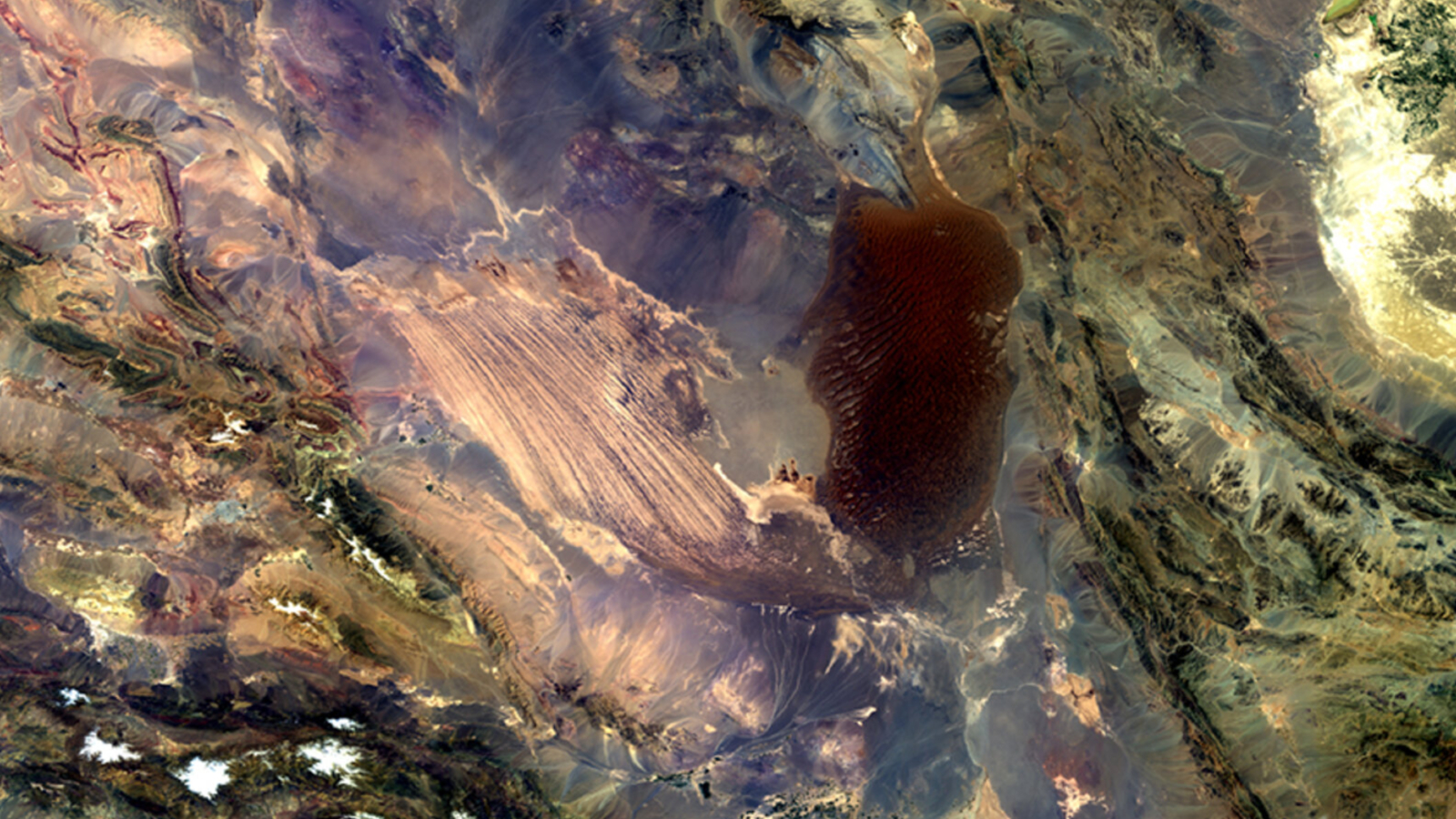

This 2012 satellite photo shows a series of giant windblown ridges, known as yardangs, and a group of towering sand dunes at the heart of Iran's Lut Desert.

Where is it? Lut Desert, Iran [30.42887793, 58.92226083]

What's in the photo? Otherworldly ridges alongside a mysterious shadowy patch

Which satellite took the photo? European Space Agency's Envisat

When was it taken? April 2, 2012

This striking false-color image shows massive wind-carved ridges and a "shadowy" patch of sand dunes at the heart of Iran's Lut Desert — one of the most extreme environments on Earth.

The Lut Desert covers more than 7,000 square miles (18,000 square kilometers) in southeast Iran. It is a salt desert, meaning its sand contains a mixture of salts and other minerals leftover from an ancient lake, and contains almost no water or vegetation. The desert's Persian name, Dasht-e Lūt, means "emptiness plain."

The region is often called the "hottest place on Earth," but this is open to interpretation. The highest air temperature on Earth within the last century — 130 degrees Fahrenheit (54.4 degrees Celsius) — was recorded at Furnace Creek Ranch in California's Death Valley in 2020. But, the ground surface temperature of the Lut Desert reached a maximum of 177.4 F (80.8 C) in 2018, which is a joint record shared with Mexico's Sonoran Desert, according to NASA. The sands get so hot in the Lut Desert partly because of large, dark patches of ancient lava that cover the surface and lie just below the sand.

The satellite image above shows two geological features: an area of parallel ridges, known as yardangs, on the left; and a giant, shadowy patch of sand dunes on the right. The photo was taken using the solar reflective spectral range — a mix of ultraviolet, visible light and infrared — which has made these features appear dark purple. When viewed from above with visible light only, these features are much less distinguishable from their surroundings, as more recent images from NASA's Terra satellite show.

Related: See all the best images of Earth from space

Yardangs are tall ridges carved from the bedrock of a desert by millennia of wind blasting. The ridges are particularly interesting because they are some of the best examples of this feature anywhere in the world, according to UNESCO. They are around 25 miles (40 kilometers) long and stand around 500 feet (150 meters) above the surrounding area.

The Lut Desert is also home to some of the world's tallest sand dunes, which are up to 1,500 feet (460 m) high, according to NASA's Earth Observatory. However, the dunes in the image only reach up to 1,000 feet (300 m) tall.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The heat and dryness of the Lut Desert make it nearly completely inhospitable to life, or an abiotic environment. However, there is a small, shallow body of water dozens of miles to the northeast of the dunes, which does enable some species to survive in this harsh landscape, according to the European Space Agency (ESA).

But away from this water source, there are likely some truly barren areas in the Lut Desert where even microbes cannot survive. "Some reports claim that research groups brought sterilized milk to the desert and left it uncovered in the shade, but the milk remained sterile," ESA representatives wrote. However, there is no record of this research online.

The region is prone to tectonic activity due to several fault lines that run below Iran and contributed to the region's ast volcanic activity. In 2003, a 6.6-magnitude earthquake rocked the country, and the epicenter was around 100 miles (160 km) south of the dunes and yardangs in the image, according to the ESA.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.