Earth's plate tectonics traced back to 'tipping point' 3.2 billion years ago

Researchers analyzing ancient deposits in Australia found evidence that Earth's layers started to get mixed up — a fingerprint of plate tectonics — about 1.3 billion years after the planet formed.

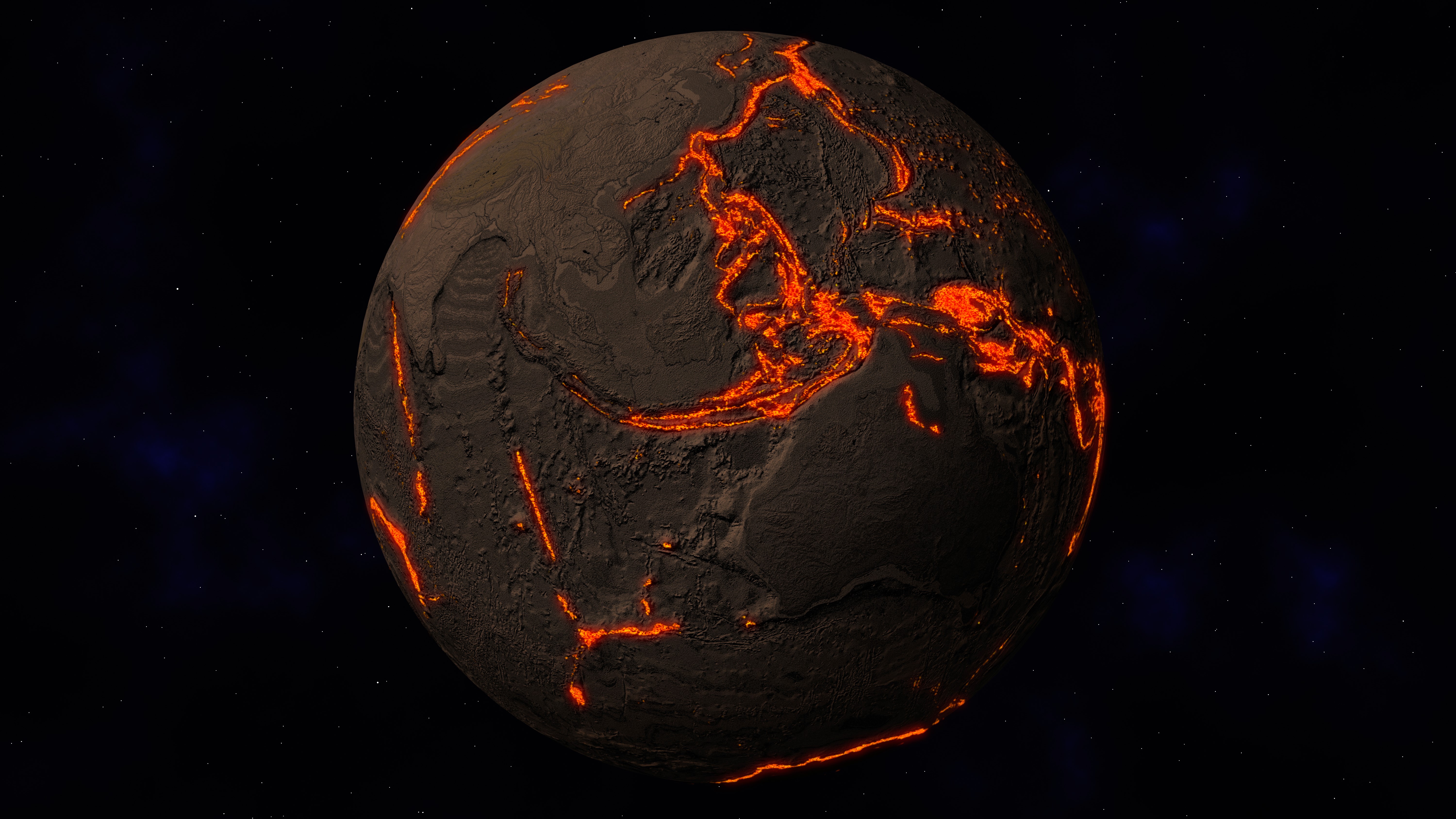

Earth's surface is ever-changing, with tectonic plates grinding and shifting, building mountain ranges, pulling apart sea floors and causing dramatic earthquakes.

Now, new research adds to the growing body of evidence that these dynamics started 3.2 billion years ago. While there is controversy within the geoscience community about exactly when Earth became more than just a blob of hot, undifferentiated rock, the new study suggests that this transition happened about 1.3 billion years after the planet formed.

"Three-point-two billion is the tipping point," study co-author Zheng Xiang Li, a geodynamicist at Curtin University in Australia, told Live Science.

In 2020, Li and his colleagues reported there was a shift in the chemistry of the rocks that formed in the mantle about 3.2 billion years ago, hinting that a "remixing" process took place. This process would have involved minerals being transported from the crust down into the mantle, and mantle rocks moving up to the surface — the fingerprints of plate tectonics. Other researchers have also seen evidence of a shift at this same time period; for example, a 2020 study in the journal Science Advances found magnetic evidence for large-scale plate motion 3.2 billion years ago.

But there is still debate about when and how these processes started, Li said.

When did plate tectonics begin?

In the new study, he and Luc Doucet, a geochemist at Curtin University, along with their colleagues, focused on large lead-zinc deposits in Australia. The scientists used the ratios of molecular variations of uranium, thorium and lead as a clock to measure events that happened deep in Earth's history.

Related: Is Africa splitting into two continents?

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The deposits in Australia span from 3.4 billion years ago to 285 million years ago, study co-author Denis Fougerouse of Curtin University said in a statement.

The new analysis again pointed at 3.2 billion years as a turning point, Li said. Before then, Earth had differentiated into the "layer cake" pattern of core, mantle and crust that is still seen today. This layering was driven by gravity, with heavier elements sinking to the core and lighter elements rising to the crust, Li said.

However, 3.2 billion years ago, these layers started to remix, with plate tectonics driving slabs of crust back into the mantle, and forces such as volcanism bringing mantle elements up to the surface.

The researchers also found that the initiation of this process was complicated and not necessarily timed exactly the same all across the planet. The new findings, reported in the August edition of the journal Earth-Science Reviews, show that researchers need to recalibrate the uranium-thorum-lead dating system to capture these nuances.

"If we don't deal with it carefully, we might have tens of millions or hundreds of millions of years of error in the age," Li said.

The researchers are now using computer simulations to understand how plate tectonics likely started 3.2 billion years ago. The cooling of the planet from a magma ocean to something more temperate and solid may have played a major role, Li said.

"Our first motivation is to document how the whole Earth evolved from the early red ball through plate tectonics to the green marble we have now," he said.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.