'Golden spike' showing the moment Earth turned into a giant snowball discovered in ancient Scottish rocks

Geological evidence of the transition when Earth was plunged into a planetary-wide deep-freeze discovered in ancient Scottish rocks.

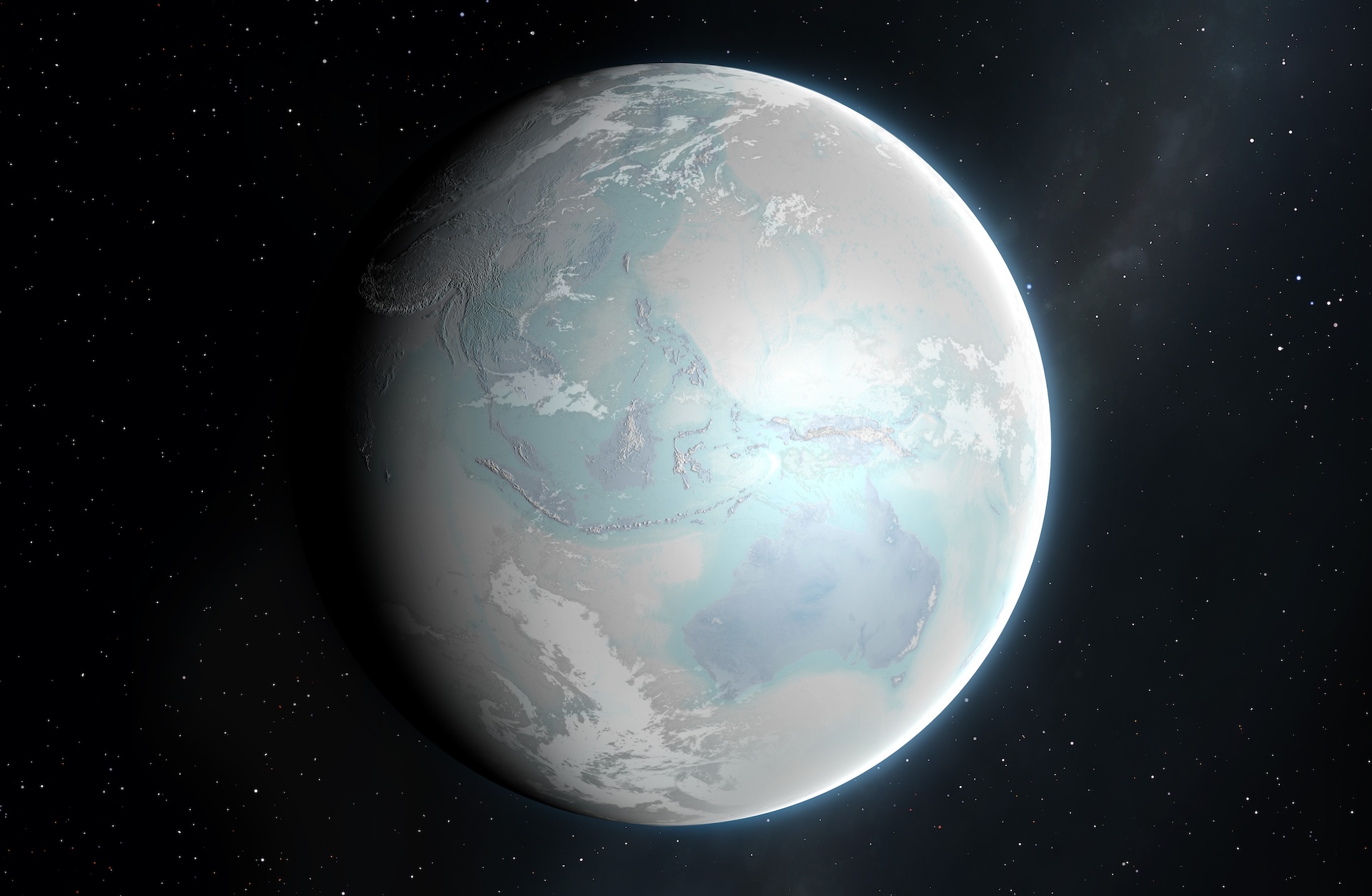

Hundreds of millions of years ago, Earth plunged into a deep-freeze that turned the planet into a giant ball of ice. Now, scientists have discovered rocks marking this moment on a remote archipelago in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland.

The rocks, dating to between 720 million and 662 million years ago, provide a rare complete record of the transition between a warm tropical environment and a "snowball Earth," where glaciers encased the globe.

If confirmed, the Garvellachs rocks could be declared a "golden spike" — a marker showing a transition to a new geological age. Specifically, these rocks would show the point when Earth moved from the Tonian period (1 billion to 720 million years ago) to the Cryogenian period (720 million to 635 million years ago).

"Most areas of the world are missing this remarkable transition because the ancient glaciers scraped and eroded away the rocks underneath, but in Scotland by some miracle the transition can be seen," study first author Elias Rugen, a researcher at University College London's Earth Sciences department, said in a statement.

Scientists believe there were two snowball Earth events during the Cryogenian — the Sturtian glaciation and the Marinoan glaciation. The former event was earlier and more severe, lasting for around 57 million years, while the latter, more poorly constrained event, lasted between 15 and 20 million years.

In a new study, published Thursday (Aug. 15) in the Journal of the Geological Society of London, researchers analyzed layers of rock 0.7 miles (1.1 kilometers) thick, along with another 230-foot-thick (70 meters) layer sitting beneath.

The researchers collected rock samples from two formations on the Garvellachs and analyzed tiny crystals called zircons. Zircons contain uranium, a radioactive element that slowly and steadily decays into lead, so the team was able to determine exactly when the rocks were formed. The researchers found that the lower section of rock formed in tropical waters, when Earth was much warmer.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"These layers record a tropical marine environment with flourishing cyanobacterial life that gradually became cooler, marking the end of a billion years or so of a temperate climate on Earth," Rugen said.

The zircon dating showed the rocks were deposited between 720 million and 662 million years ago — a period that encompassed the transition between the geological periods, from the temperate Tonian and into the Sturtian glaciation and Cryogenian period.

In July, representatives from the International Commission on Stratigraphy, which is part of the International Union of Geological Sciences, went to the Garvellachs to assess whether the site is a geological marker. If it is ratified, the site will be marked with a golden spike.

"The layers of rock exposed on the Garvellachs are globally unique," Rugen said.

Hannah Osborne is the planet Earth and animals editor at Live Science. Prior to Live Science, she worked for several years at Newsweek as the science editor. Before this she was science editor at International Business Times U.K. Hannah holds a master's in journalism from Goldsmith's, University of London.