How many tectonic plates does Earth have?

The number varies from a dozen to almost 100 — and most of these don't even appear on official maps.

Billions of years ago, Earth's surface was a sea of molten rock. As this simmering magma gradually cooled, it formed a continuous, rocky shell, with the denser minerals coalescing toward the planet's interior and the less-dense minerals rising to the surface.

"That is how the plates formed at the surface of the Earth," Catherine Rychert, a geophysicist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts, told Live Science. "The plate is the crust, then a bit of the mantle beneath it …. Beneath that you have weaker material."

This weaker material is hotter and mobile. The difference in strength between these layers is what allows the overlying plates to move — colliding, diverging and grating against one another. In these zones, rifts and mountains form, and volcanoes and earthquakes spark to life.

But how many of these plates cover Earth's surface? The answer ranges from a dozen to nearly 100, depending on how you look at it.

Related: What's inside Earth?

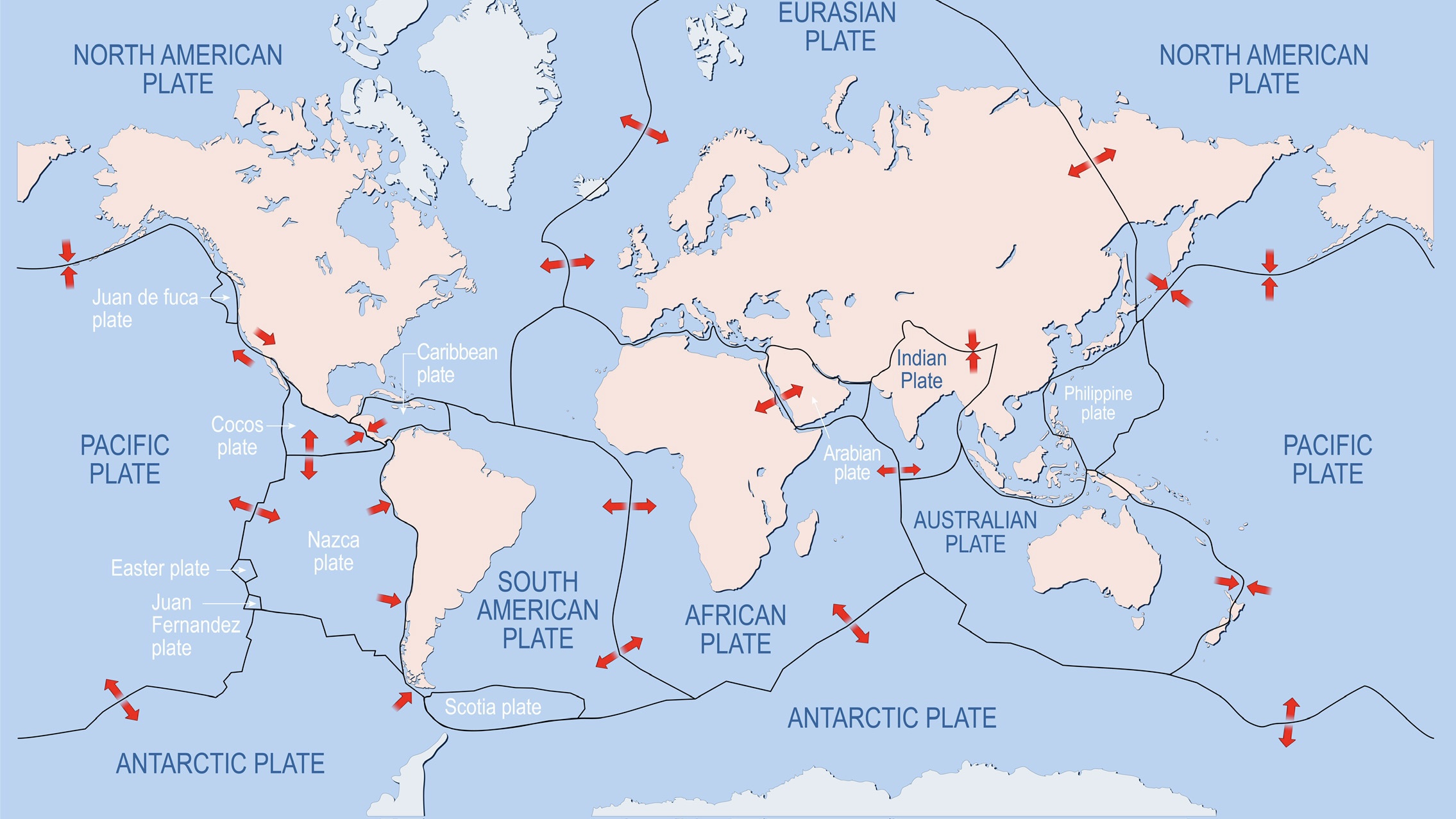

Most geologists agree that there are between 12 and 14 "primary" plates that cover most of Earth's surface, said Saskia Goes, a geophysicist at Imperial College London. Each has an area of at least 7.7 million square miles (20 million square kilometers), with the largest being the North American, African, Eurasian, Indo-Australian, South American, Antarctic and Pacific plates. The most monumental of these is the Pacific Plate, which spans a whopping 39.9 million square miles (103.3 million square km), closely followed by the North American Plate, which covers 29.3 million square miles (75.9 million square km).

"In addition to the seven very large [plates], there are five more somewhat smaller ones: Philippine Sea, Cocos, Nazca, Arabian and the Juan de Fuca," Goes told Live Science. Some geologists count the Anatolian Plate (part of the larger Eurasian Plate) and the East African Plate (part of the African Plate) as separate entities, "as they are moving at speeds that are clearly different from these main plates," Goes said. That explains why the main plate estimate ranges from 12 to 14.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Things grow more complicated when you look at plate boundaries, where plate tectonics causes plates to splinter into smaller fragments called microplates. These have an area of less than 386,000 square miles (1 million square km), and some scientists estimate that there are about 57 on Earth. But they usually aren't included on world maps — a discrepancy that reflects some uncertainty about how they form.

"The number of microplates will keep on changing, depending on how different scientists choose to define them, and as we learn more about how and where the deformation at plate boundaries localizes," Goes said.

As geologists make sense of this dynamic puzzle, Earth's moving plates create some fascinating scenarios. The Pacific Plate is probably the fastest, moving northwest 2.8 to 3.9 inches (7 to 10 centimeters) per year, Rychert said.

"The fast motion is caused by a surrounding ring of subduction zones, otherwise known as the Ring of Fire, where gravitational forces are pulling the plates down into the Earth," she said, adding that the constant motion may even be consuming continents. "We think that sometimes continents founder, and a piece will actually fall off into the mantle," Rychert said.

With these dramatic forces at play, what our planet's plate-encrusted surface will look like another few billion years from now remains a mystery.

Emma Bryce is a London-based freelance journalist who writes primarily about the environment, conservation and climate change. She has written for The Guardian, Wired Magazine, TED Ed, Anthropocene, China Dialogue, and Yale e360 among others, and has masters degree in science, health, and environmental reporting from New York University. Emma has been awarded reporting grants from the European Journalism Centre, and in 2016 received an International Reporting Project fellowship to attend the COP22 climate conference in Morocco.