Hranice Abyss: The deepest freshwater cave on Earth and a conduit to a 'fossil' sinkhole

Scientists first described the flooded cave in 2016 but determined its extraordinary extent years later.

Name: Hranice Abyss

Location: Hranice, Czech Republic

Coordinates: 49.53214473576795, 17.750610529720298

Why it's incredible: The cave is so deep, the world's tallest building could fit inside it.

The Hranice Abyss — or "Hranická propast," in Czech — is the deepest known freshwater cave in the world. Geologists think it could extend more than half a mile (1 kilometer) below Earth's surface, which is more than twice as deep as the world's next-deepest freshwater cave.

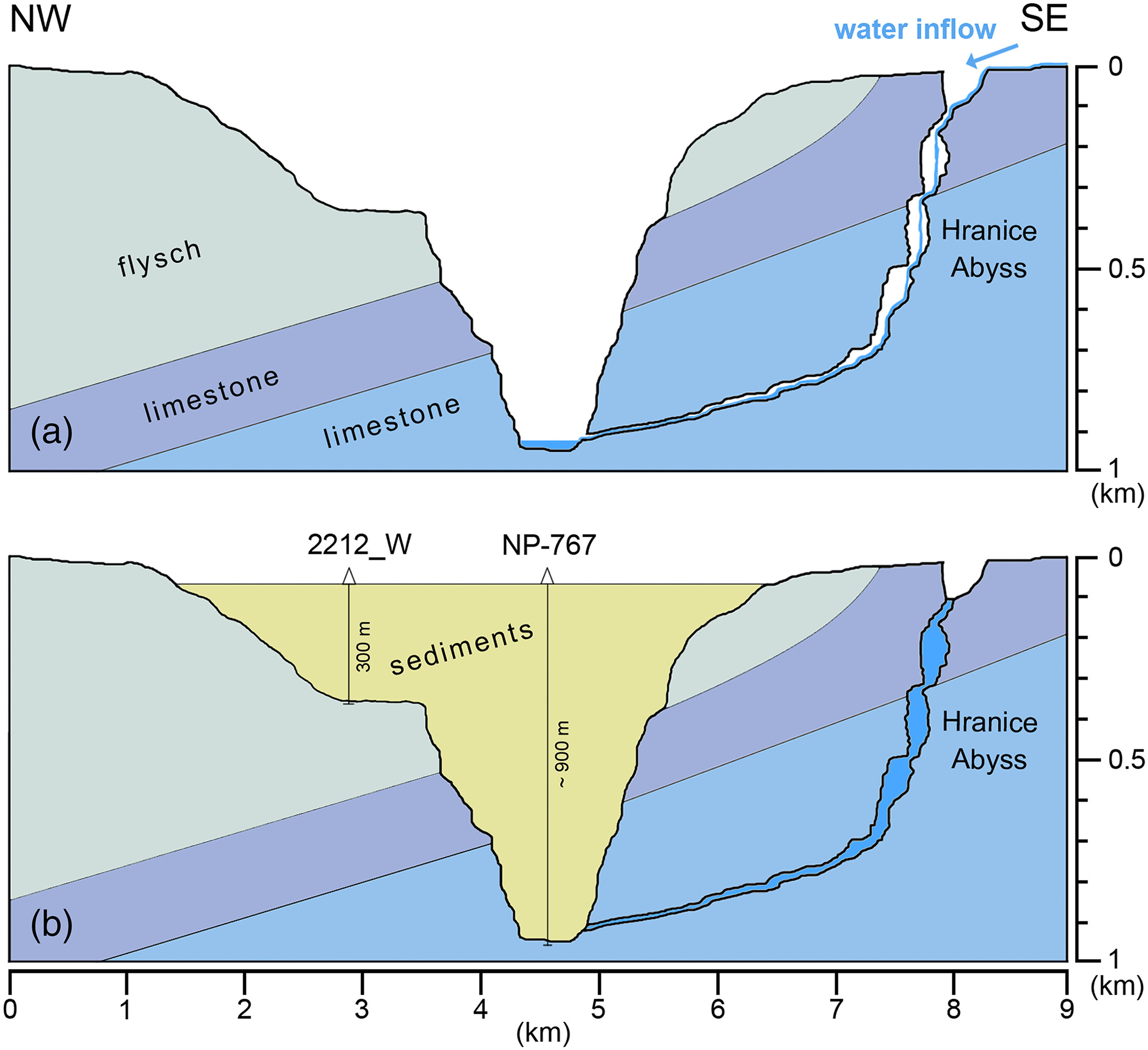

The Hranice Abyss challenges a long-held scientific belief that deep caves open from the bottom up, with warm, acidic groundwater rising and dissolving the bedrock. According to a 2020 study in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface, that's not how the abyss formed. Instead, evidence shows water carved the cave from the top down.

Related: Deepest blue hole in the world discovered, with hidden caves and tunnels believed to be inside

Scientists first described the Hranice Abyss in 2016, after conducting numerous dives inside the cave. Researchers then deployed a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) to explore the corners that divers couldn't reach and measured a maximum depth of 1,553 feet (473.5 m), according to the 2020 study.

This established the Hranice Abyss as the deepest freshwater cave in the world, beating Italy's Pozzo del Merro, which descends 1,286 feet (392 m) below the surface. However, the recorded depth was constrained by the length of a fiber-optic communication cable attached to the ROV.

The 2020 study used gravity and seismic imaging methods to investigate the true extent of the Hranice Abyss. The results suggested the cave was more than twice as deep as the ROV had previously gone — and deep enough to fit the world's tallest building, the Burj Khalifa, which stands 2,717 feet (828 m) tall.

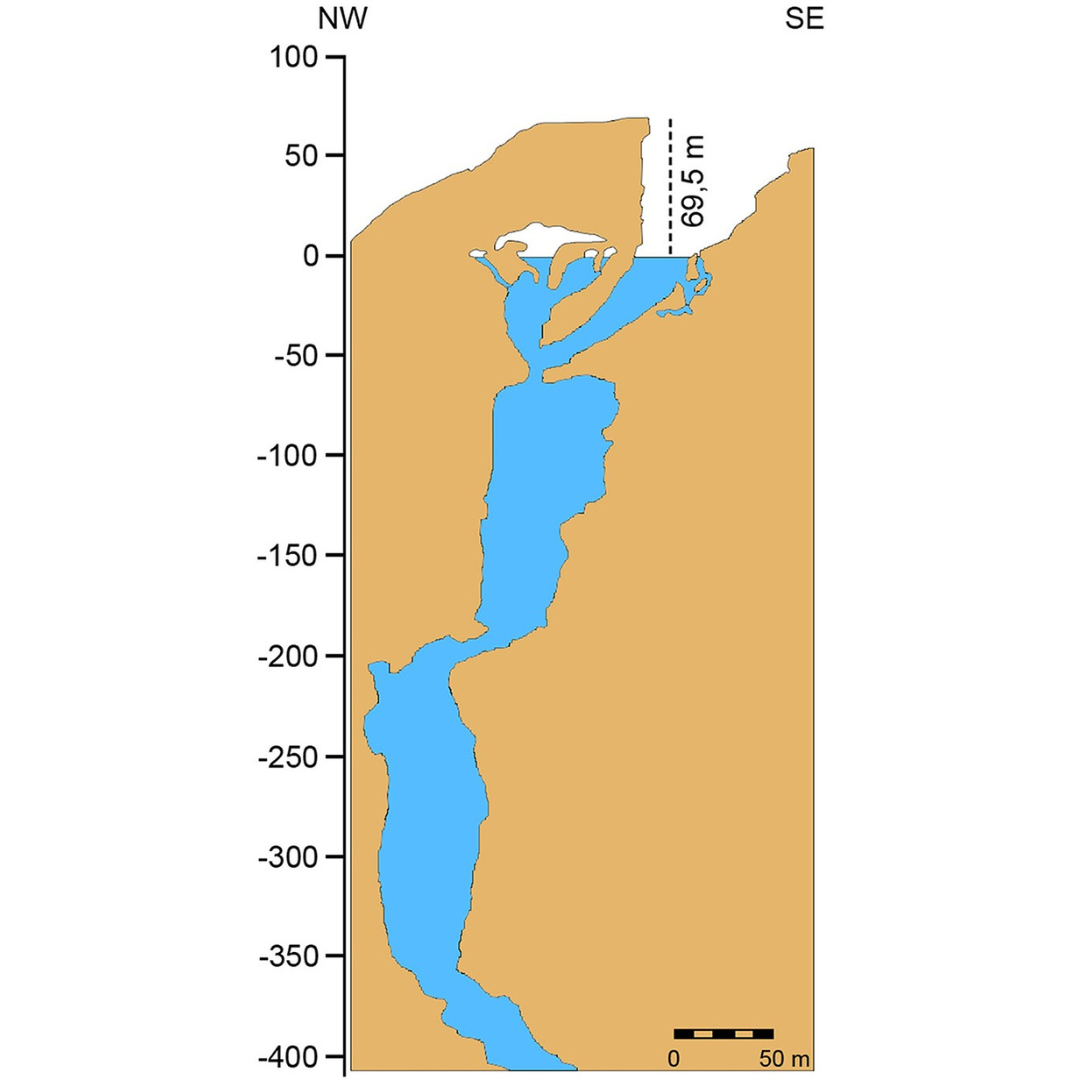

The opening of the Hranice Abyss is an inclined cavity with a small lake at the bottom, according to the latest study. The underwater portion of the cave is an irregular, vertical cylinder ranging from 30 to 100 feet (10 to 30 m) in diameter. Water temperatures in the cave vary between 58 and 66 degrees Fahrenheit (14.5 to 18.8 degrees Celsius) depending on the time of year.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The extended mapping also revealed that the bottom of the cave is connected to a nearby "fossil" sinkhole called the Carpathian Foredeep. This sinkhole, which is around 1.2 miles (2 km) from the cave's entrance, opened roughly 19 million years ago and was subsequently filled with sediment, meaning it is not visible at the surface today.

The Hranice Abyss formed after the sinkhole, between 16 million and 14 million years ago, as water at the surface began percolating down through soluble rocks such as limestone. This created a cavity that deepened over time, eventually forming a channel through which water flowed from the surface to the bottom of the sinkhole. But when sediment eventually blocked the opening inside the sinkhole, water began accumulating inside the channel, paving the way for the cave to fill with water.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.