Earth's crust swallowed a sea's worth of water and locked it away beneath Pacific seafloor

Porous rock that formed during one of Earth's biggest volcanic eruptions absorbed so much water as it eroded that it created a huge reservoir over the eons, now buried deep in Earth's crust.

A massive water reservoir is hidden deep beneath the ocean floor off the coast of New Zealand — and it may explain why the region experiences slow-motion earthquakes, scientists have found.

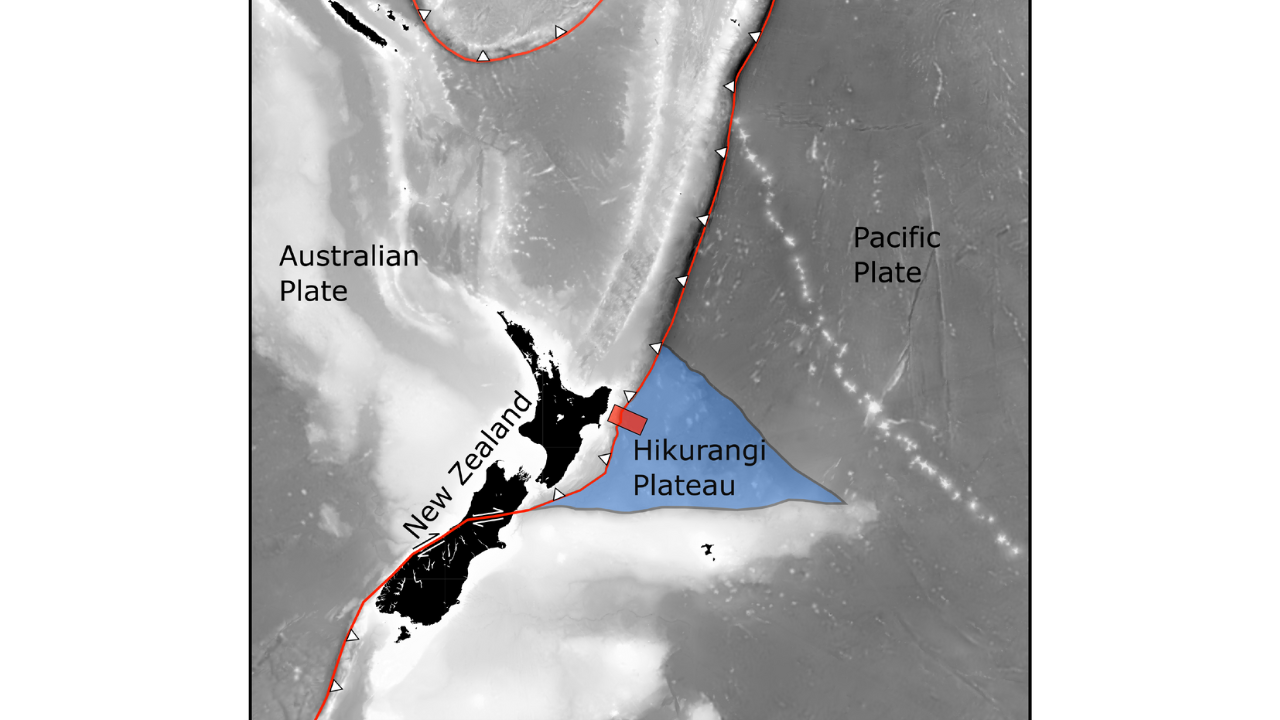

A sea's worth of water became locked inside volcanic rocks that formed 120 million to 125 million years ago during the early Cretaceous, when a lava plume the size of the U.S. burst through Earth's crust and solidified into a vast plateau, researchers said in a statement. Thick layers of sediment have since blanketed these rocks and buried any trace of their explosive past 2 miles (3 kilometers) below the Pacific Ocean seabed.

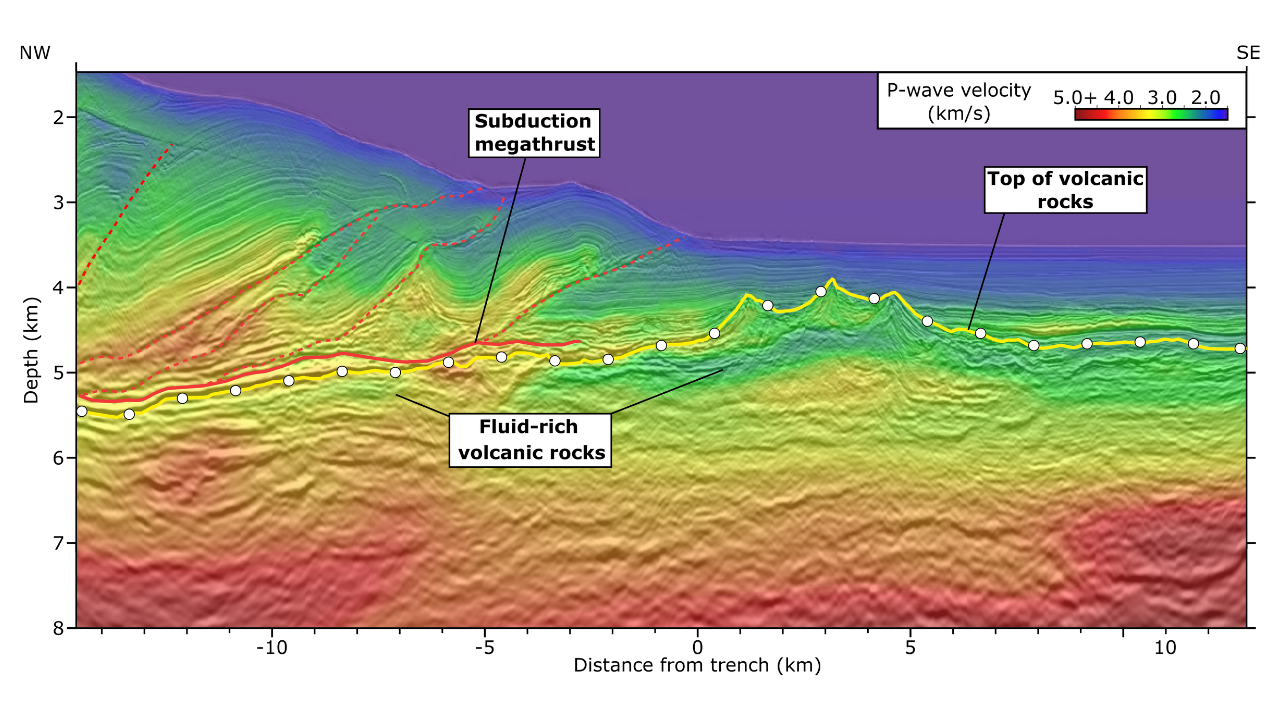

The researchers mapped a fault line along the east coast of New Zealand's North Island and found that these ancient rocks were abnormally "wet," with water making up nearly half the volume of cores drilled up from the ocean floor.

"Normal ocean crust, once it gets to be about seven or 10 million years old, should contain much less water," study lead author Andrew Gase, a marine geophysicist and seismologist who conducted the research while at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG), said in the statement.

Related: Secrets of 'mystery sandwich' beneath Yellowstone revealed in new map

Shallow seas that surrounded the ancient volcanic plateau may have eroded the rocks into a porous honeycomb, which sponged up water and stored it like an aquifer, according to the statement. This water-logged terrain slowly transformed over the eons, absorbing more water as the rocks were ground into clay and became buried.

Researchers discovered this underwater reservoir 9.3 miles (15 km) from the Hikurangi fault, or subduction zone, where the Pacific tectonic plate dives under the Australian plate and into Earth's mantle. The friction between these plates produces unusual, slow-motion earthquakes that can last for months and cause almost no damage at Earth's surface. Also known as "slow slip" events, these earthquakes only occur in a handful of places across the globe, including in the Pacific Northwest, Japan, Mexico and New Zealand.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Slow slip events are often linked to buried water stores, according to the statement. As one tectonic plate slides under another, water contained in the rocks may create high-pressure conditions that slow the process and prevent sudden slips.

The newly discovered water reservoir may be to thank for the harmless, slow-motion earthquakes that occur every one or two years at the Hikurangi fault, according to the study, published Aug.16 in the journal Science Advances.

"This is something that we've hypothesized from lab experiments and is predicted by some computer simulations, but there are very few clear field experiments to test this at the scale of a tectonic plate," study co-author Demian Saffer, the director of UTIG and a professor in the Department of Earth and planetary sciences, said in the statement.

The researchers used seismic scans to build a 3D image of the underwater region and discover the reservoir. But to determine how far it stretches into the crust and confirm its effect on pressure around the fault, they will have to drill deep down into the ocean floor, Gase said.

"We can't see deep enough to know exactly the effect on the fault, but we can see that the amount of water that's going down here is actually much higher than normal," he said.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.