Scientists discover ghost of ancient mega-plate that disappeared 20 million years ago

A long-lost tectonic plate dubbed 'Pontus' that was a quarter of the size of the Pacific Ocean was discovered by chance by scientists studying ancient rocks in Borneo.

A long-lost tectonic plate that once underpinned what is today the South China Sea has been rediscovered 20 million years after disappearing.

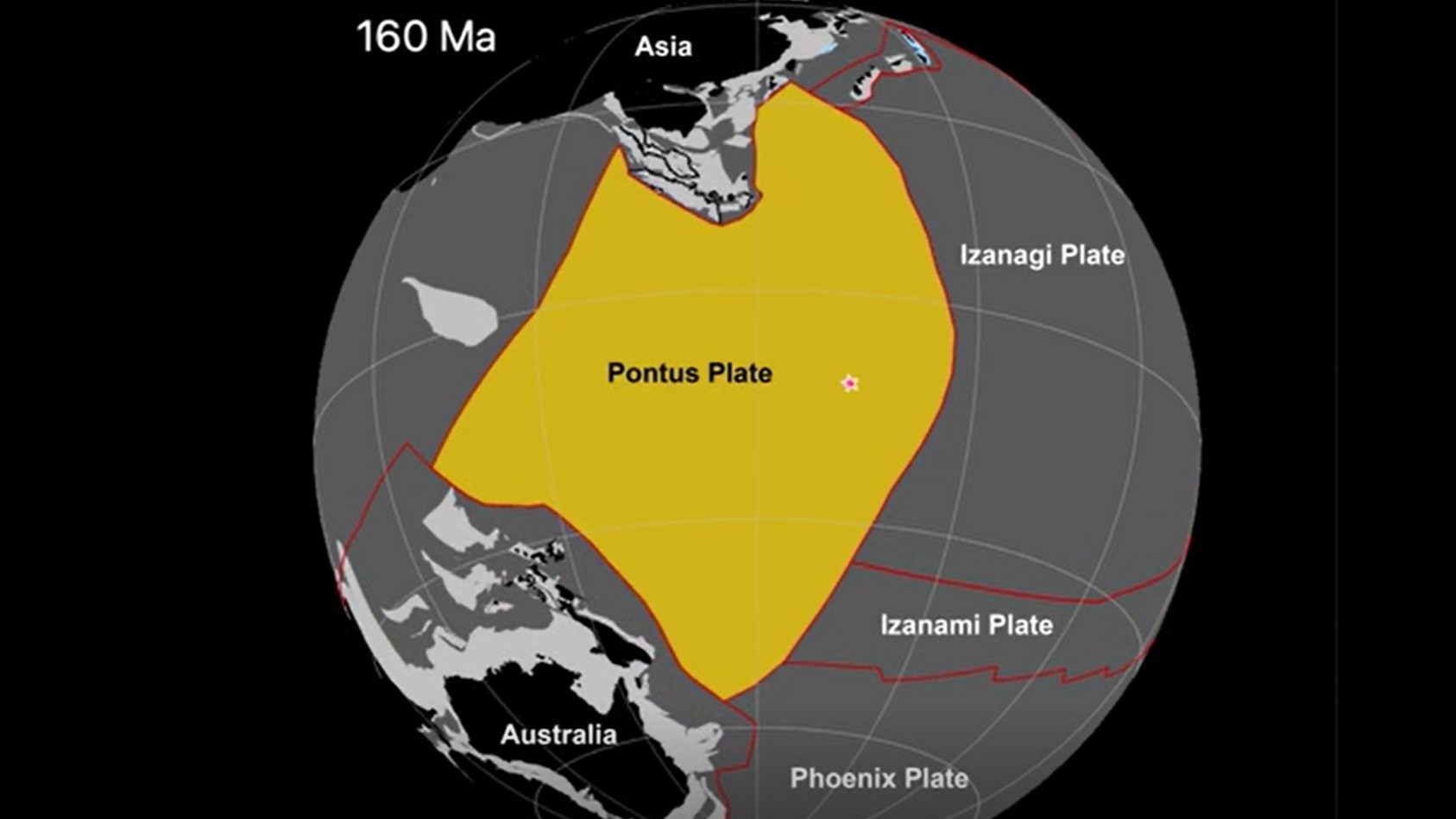

The plate is known only from a few rock fragments from the mountains of Borneo and the ghostly remnants of its huge slab detected deep in Earth's mantle. It was once a quarter of the size of the Pacific Ocean. Scientists have dubbed it the "Pontus plate" because at the time of its existence, it sat under an ocean known as the Pontus Ocean.

"It's surprising to find remnants of a plate that we just didn't know about at all," Suzanna van de Lagemaat, a doctoral candidate at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, told Live Science.

Van de Lagemaat and her colleagues were initially studying the Pacific plate under the Pacific Ocean. Tectonic plates constantly move against one another, and the crust in oceanic plates is more dense than continental plates, so oceanic plates get pushed under continental plates in a process called subduction and disappear. Sometimes, however, rocks from a lost plate get incorporated into mountain-building events. These remnants can point to the location and formation of ancient plates.

The researchers were attempting to find remnants of one of these ancient lost plates, known as the Phoenix plate, while doing fieldwork in Borneo. Scientists can look at the magnetic properties of rocks to learn when and where they formed, van de Lagemaat said; the magnetic field that surrounds Earth gets "locked in" to rocks when they form, and that magnetic field varies by latitude.

Related: Fountains of diamonds erupt from Earth's center as supercontinents break up

But the researchers found something strange when they analyzed the rock they'd collected in Borneo.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"This latitude didn't fit with the latitude we got from the other plates that we already knew about," van de Lagemaat said.

To unravel the mystery, she used computer models to investigate the region's geology over the last 160 million years. The plate reconstruction showed a hiccup between what is now South China and Borneo — an ocean once thought to be underpinned by another ancient plate called the Izanagi plate actually wasn't on that plate. Instead, the Borneo rocks fitted into that mystery gap.

The researchers discovered the spot was actually occupied by a never-before-known plate, which van de Lagemaat and her team named the Pontus plate.

The reconstruction, published Sept. 29 in the journal Gondwana Research, shows that the Pontus plate formed at least 160 million years ago but was probably far older. (The rock samples collected in Borneo date back 135 million years.) It was once enormous but shrank steadily over its lifespan, finally getting pushed under the Australian plate to the south and China to the north, disappearing 20 million years ago.

Decade-old research from the same lab also showed a hint of the Pontus plate. That research looked at imaging of Earth's middle layer, the mantle, where the subducted crust ends up. It showed a huge slab of crust of unknown origin, but scientists at the time had no way to determine where it came from, van de Lagemaat said. Now, it's clear that this crust is what's left of the Pontus plate.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.