Scientists extract a kilometer of rock from Earth's mantle in record-breaking mission

A record-breaking drilling attempt, which dug more than a kilometer into an underwater mountain in the Atlantic Ocean, has given scientists a treasure trove of rocks to study for clues to Earth's inner workings.

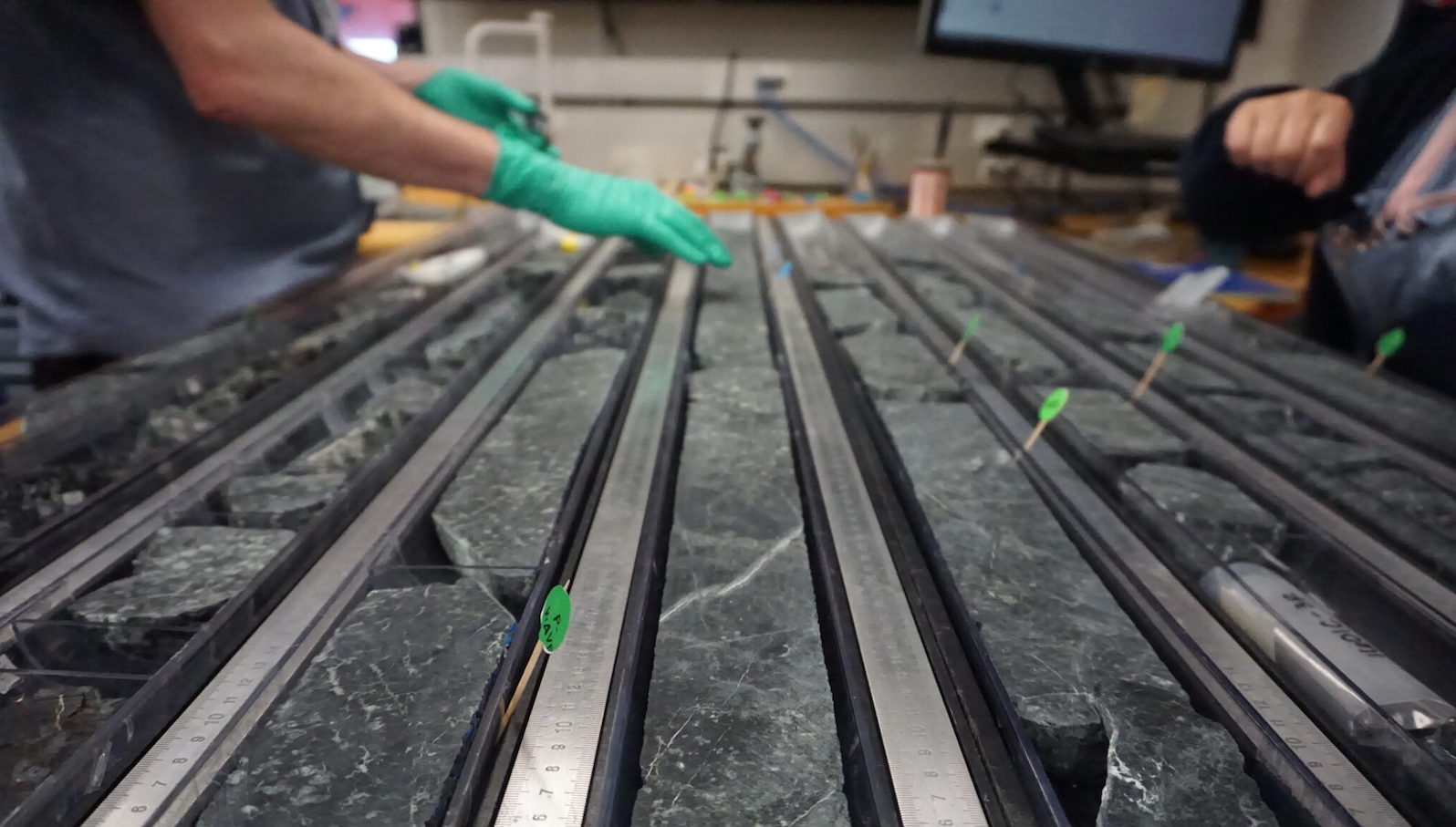

For the first time, scientists have drilled into an underwater mountain to collect a record-breaking chunk of Earth's mantle — a core of rock that's more than 3,280 feet (1 kilometer) long.

The stunning feat was achieved by drilling into Atlantis Massif, an underwater mountain located on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge deep beneath the North Atlantic Ocean. By aligning a drill at this location, geologists punched a hole as deep as 4,156 feet (1,267 meters) into the mountain and extracted a "staggering" amount of serpentinite rocks — metamorphic rocks that form at deep tectonic-plate boundaries — from Earth's interior.

Despite the groundbreaking findings, this isn't the deepest a drill has ever gone into the seabed, and technically, it didn't dig into Earth's mantle. Instead, the researchers took advantage of a "tectonic window" — a region where mantle rocks have been pushed above their usual resting place — to sink the drill and extract the material.

Related: Earth's mantle has a gooey layer we never knew about

"On Earth, mantle rock is normally extremely difficult to access," the geologists wrote in a blog post. "The Atlantis Massif offers a rare advantage to gain access to it, as it is composed of mantle rocks that have been brought up closer to the surface through the process of ultra-slow seafloor spreading."

Geologists have been trying to extract significant tranches of Earth's mantle since 1961, when scientists at Project Mohole attempted to drill beneath the Pacific Ocean to reach the Mohorovičić discontinuity, the region where Earth's crust gives way to its mantle. Unfortunately, the project's drill made it only 601 feet (183 m) below the seabed before it foundered and the attempt was scrubbed. Following this, a number of subsequent ocean-drilling efforts also ended without any success.

This has meant that to study chunks of Earth's mantle for clues into diverse processes such as volcanism and the planet's magnetic field, scientists have had to rely on rock chunks spat out from volcanic eruptions, all of which have been altered by their journey to the surface.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The geologists, members of the International Ocean Discovery Program aboard the JOIDES Resolution scientific drilling vessel, embarked on their mission to Atlantis Massif not because they wanted to extract mantle cores, but because they were searching for the origins of life on Earth. Massif's rocks contain olivine, which reacts with water in a process called serpentinization to produce hydrogen, an essential food source for microbial life.

Yet, soon after May 1, when they landed their drill in a horizontal fault in the seabed, the researchers extracted a record-breaking core of upper mantle rock that stretched more than 3,280 feet long.

The rock was mainly peridotite, a coarse igneous rock that is filled with olivine and pyroxene and is the most common rock type in the upper mantle. Some signs of the rock being altered by interactions with seawater could mean it is from the lower crust and not the upper mantle, but the scientists are still drilling for even deeper samples to put their discovery beyond doubt. Inside these rocks lies a treasure trove of information that geologists will pore over to learn more information about Earth's inner workings.

"The magnitude of the history occurring has most certainly not been lost on our science party, many of whom are seasoned field researchers and believe this will be incredibly important data for many generations of scientists to come," the geologists wrote in the blog post.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.