Scientists find strange underwater volcano that 'looks like a Bundt cake'

The Saildrone Surveyor mission discovered the unnamed, 3,200-foot-tall formation in February while mapping the seafloor off the coast of California.

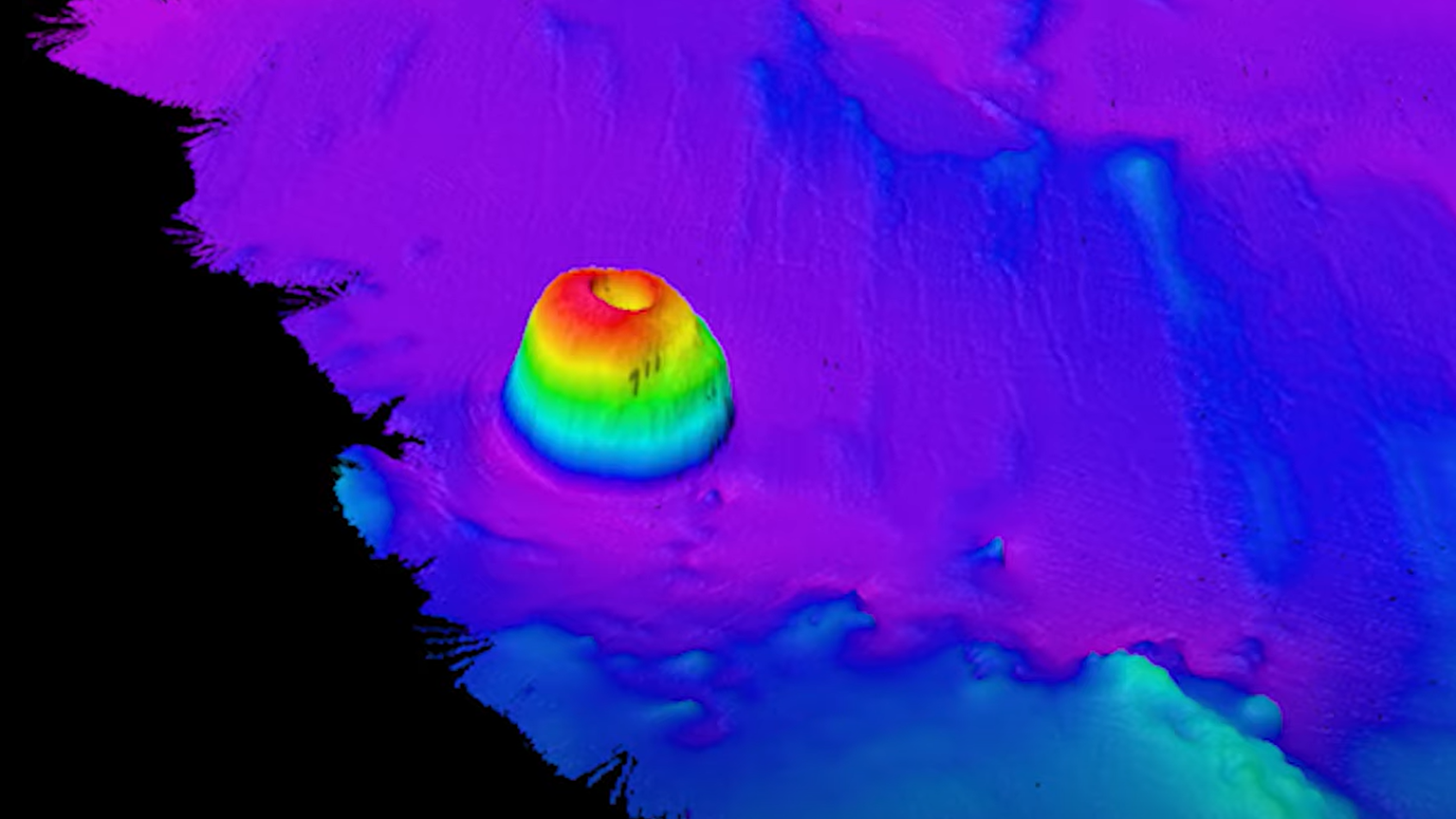

A strange underwater mountain towering above the seafloor "like a Bundt cake" has been discovered off the coast of California by an uncrewed sailing ship mapping the North Pacific, according to the mission team.

The unnamed, 3,200 foot (975 meter) tall formation falls just short of the required size for a seamount — at least 3,300 feet (1,000 m) above the surrounding seafloor, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Nonetheless, oceanographers have referred to the feature as such because, like other seamounts, it is an underwater mountain with steep sides rising from the seafloor and the remnant of an extinct volcano.

Underwater mountains formed by volcanic activity sometimes poke through the ocean surface and give rise to islands, such as Hawaii. But this one is entirely submerged, with a crowning crater still visible 1,200 feet (366 m) below sea level.

Apart from its crater, this strange seamount looks nothing like a volcano. "Typically seamounts have sloped sides, like Mount Fuji," Aurora Elmore, program manager for NOAA's Ocean Exploration Cooperative Institute, told SFGATE. "But what's interesting about this one is that it's really steep. It rises from the bottom of the seafloor with a tower shape."

The Saildrone Surveyor — the world's largest uncrewed ocean mapping vehicle — detected the bizarrely shaped mountain 200 miles (322 kilometers) off the coast of northern California. It stands outside the area where seamounts are usually found near the coast, which means the discovery "expands the range" of seamounts, Elmore said.

Related: Nuclear-powered US submarine collided with a hidden underwater mountain, Navy reveals

When they first saw the seamount on multibeam sonar images, "the immediate reaction from the team was that it looked like a Bundt cake," Neah Baechler, a hydrographer with the Ocean Exploration Trust and lead surveyor for Saildrone, told The Sacramento Bee. "It's very round and with steep sides and a curved top that slopes into a crater at the center."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The tall doughnut shape may be the result of intense and rapid volcanic activity or a pileup of marine detritus — "millennia of fish poop" — that sharpened the slopes, Elmore said. While this type of formation exists elsewhere on the ocean floor, it is rare to find one (almost) big enough to qualify as a seamount.

"The fact that we can still find these things is really exciting," Jon Copley, a professor of deep-sea ecology and ocean exploration at the University of Southampton in England, told Live Science. "The majority of seamounts around the world — and there are many thousands of them — are formed as undersea volcanoes. This one looks like it would have formed as an underwater volcano because it has a crater."

Seamounts are crucial habitats for marine life because they provide hard, rocky surfaces for creatures to attach to, Copley explained. These are hard to come by in the deep sea, which is mostly covered in loose, muddy sediment. "Seamounts can be too steep for mud to stick to, and some animals really thrive on the sides," Copley said. "When one sticks up, it creates strong currents for filter feeders to grow up into the water and catch food, and you get deep-sea coral and sponge gardens growing there."

Whether the Bundt cake-shaped mountain will officially qualify as a seamount will probably be up to the committee that names underwater features — the General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans' Sub-Committee on Undersea Feature Names, which operates under the International Hydrographic Organization and the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (of UNESCO) — Copley said.

The Saildrone Surveyor discovered the feature in February, but the vessel's journey through the North Pacific began in July 2022. The ship first mapped the unknown contours of the seafloor around Alaska's Aleutian Islands before cruising down along the coast of California, according to a statement.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.