Seamount twice the size of world's tallest building discovered 'hidden under the waves'

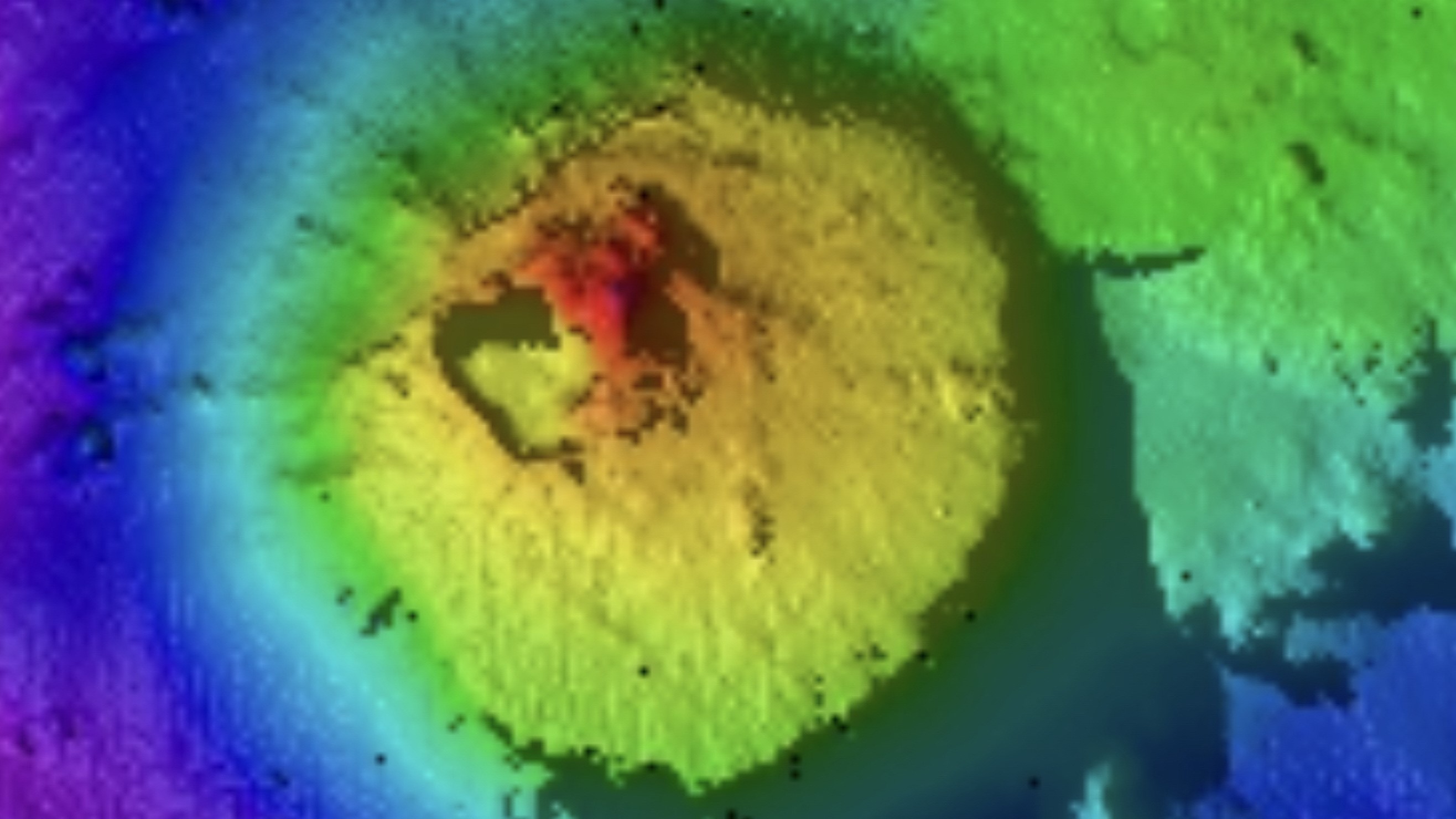

Scientists aboard the Falkor (too) research vessel have documented, for the first time, an extinct volcano towering 5,250 feet above the seabed in international waters in the Pacific Ocean.

Ocean explorers mapping the seabed off the coast of Guatemala have discovered a mountain twice as high as the Burj Khalifa, the world's tallest building, hiding deep beneath the waves.

The 5,250-foot-tall (1,600 meters) formation is a seamount — a large, underwater geological feature typically formed from an extinct volcano. Scientists discovered the cone-shaped seamount 7,870 feet (2,400 m) below sea level during an expedition organized by the Schmidt Ocean Institute this summer, according to a statement shared with Live Science.

"A seamount over 1.5 kilometers tall which has, until now, been hidden under the waves really highlights how much we have yet to discover," Jyotika Virmani, the executive director of Schmidt Ocean Institute, said in the statement.

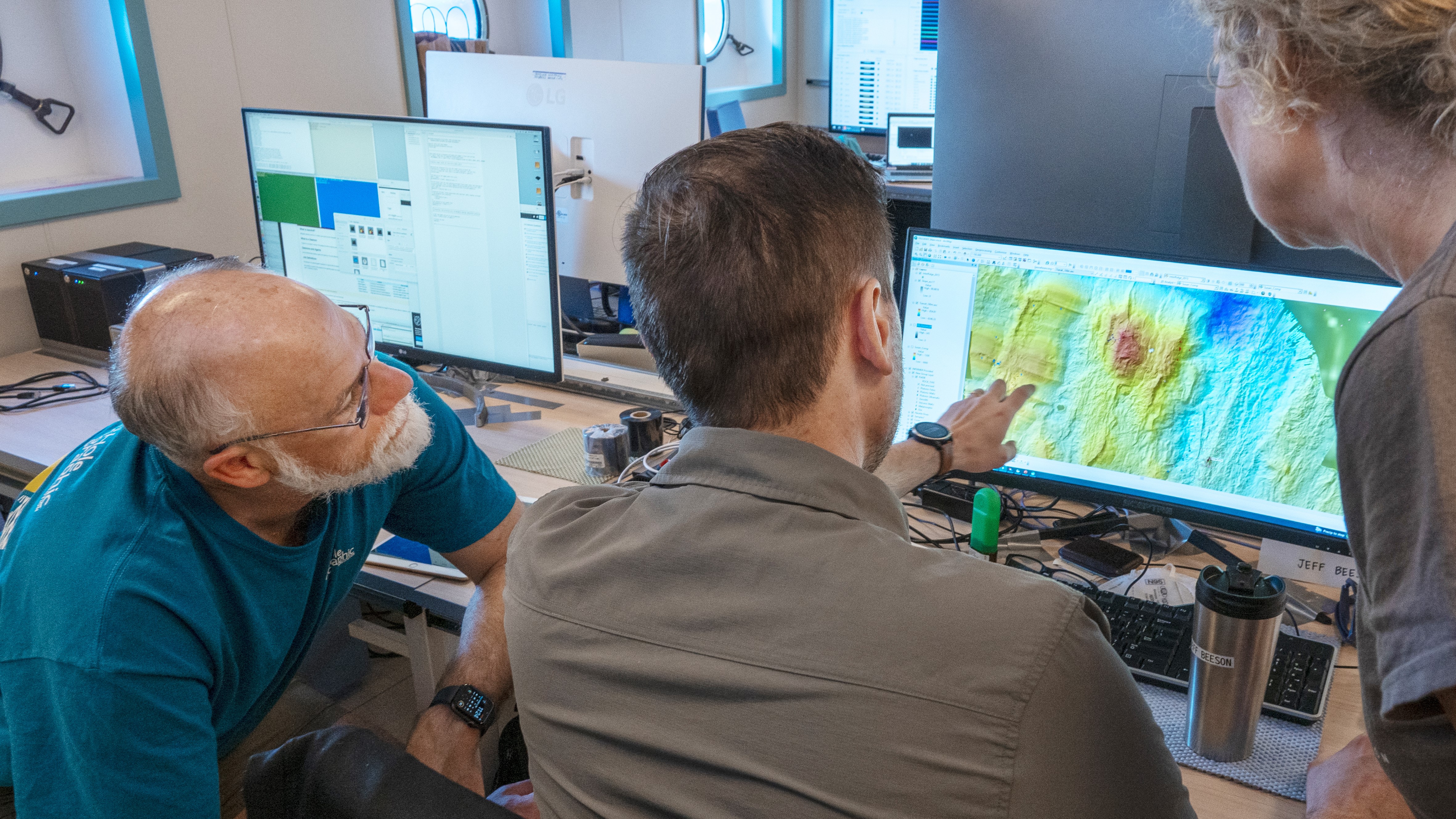

The towering feature covers 5.4 square miles (14 square kilometers) and sits in international waters in the Pacific Ocean, 97 miles (156 kilometers) from Guatemalan waters. The researchers detected the seamount using multibeam sonar mapping during a six-day crossing from Costa Rica to the East Pacific Rise — the boundary between six tectonic plates, including the Pacific plate to the west and the North American plate to the northeast.

Seamounts provide crucial rocky habitats for deep-sea corals, sponges and a host of invertebrates, as hard substrate can be difficult to come by in the ocean, with the majority of the seabed covered in loose, muddy sediment.

"Seamounts can be too steep for mud to stick to, and some animals really thrive on the sides," Jon Copley, a professor of deep-sea ecology and ocean exploration at the University of Southampton in the U.K, previously told Live Science. "When one sticks up, it creates strong currents for filter feeders to grow up into the water and catch food."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Satellite data suggest there are more than 100,000 unexplored seamounts that will come to light through continued seafloor mapping. "A complete seafloor map is a fundamental element of understanding our ocean," Virmani said. "It's exciting to be living in an era where technology allows us to map and see these amazing parts of our planet for the first time!"

In April, a research team on a Schmidt Ocean Institute mapping expedition aboard Falkor (too) revealed three new hydrothermal vent fields on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. In August, they announced the existence of a hidden underworld filled with sea creatures on the East Pacific Rise. Scientists aboard the same vessel also recently discovered two uncharted seamounts and pristine coral reefs near the Galápagos Islands.

The latest find is "yet another breathtaking discovery," Jamie McMichael-Phillips, the director of the Seabed 2030 project, which aims to map the entire seafloor by the end of the decade together with the Schmidt Ocean Institute and other partners, said in the statement.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.