'The difference between alarming and catastrophic': Cascadia megafault has 1 especially deadly section, new map reveals

The Cascadia subduction zone is more complex than researchers previously knew. The new finding could help scientists better understand the risk from future earthquakes.

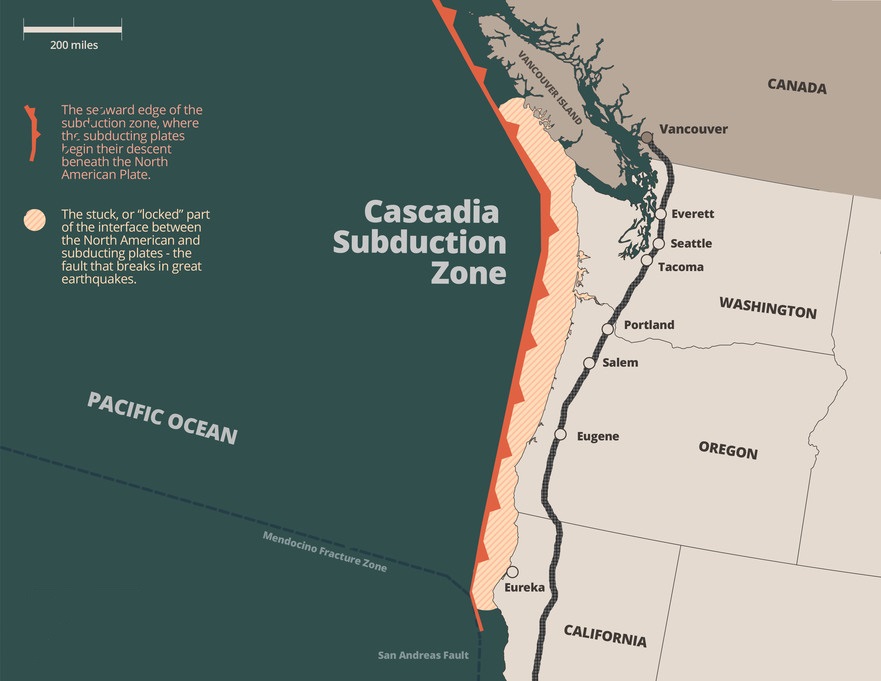

The Cascadia subduction zone has the potential to rock the Pacific Northwest and British Columbia with devastating earthquakes. Now, a closer-than-ever look at the megafault's structure reveals it is segmented into multiple major regions.

These regions might rupture individually or they could all unleash a massive temblor at once. But the findings indicate that the experience of a quake might be different in each zone.

"It requires a lot more study, but for places like Tacoma and Seattle, it could mean the difference between alarming and catastrophic," study co-author Harold Tobin, a geophysicist at the University of Washington said in a statement.

In many subduction zones, where oceanic crust grinds underneath lighter continental crust, small and medium-size earthquakes are common. These mini-quakes give researchers information about what the hidden portions of tectonic plates look like and where various faults are located.

Related: Sleeping subduction zone could awaken and form a new 'Ring of Fire' that swallows the Atlantic Ocean

But Cascadia, which stretches 600 miles (1,000 kilometers) from Northern Vancouver Island to Cape Mendocino, California, rarely throws off small quakes, lead author Suzanne Carbotte, a marine geophysicist at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University, told Live Science. So the best view scientists had of its structure came from research in the 1980s that used shipboard instruments to send small bursts of seismic waves into the crust and then record the returning waves to make images of the subsurface.

Today's instruments are much more sophisticated, Carbotte said, but no one had done a repeat study of the region. So in 2021, the researchers behind the new study gathered new seismic data along the fault.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The data covered 560 miles (900 km) of the boundary between the continental North American plate and the oceanic plates Juan de Fuca, Explorer and Gorda, all of which are plunging beneath North America at a rate of 1.2 to 1.6 inches (30 to 42 millimeters) per year .

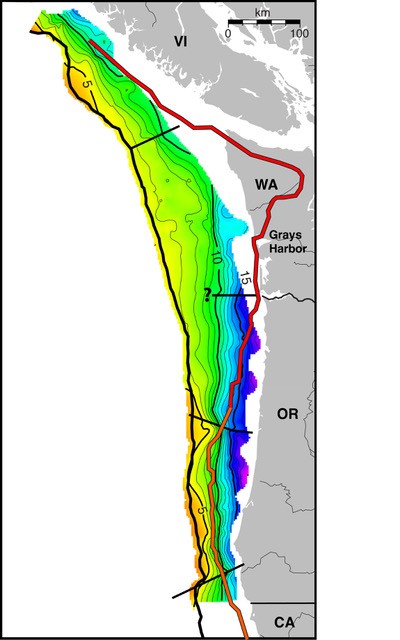

The data revealed that as the oceanic crust is subducting, or diving down, it is also breaking up. "Now that we have actual information spanning the whole region we know that the fault surface is much more complex in its geometry than the picture we had from that very old data," Carbotte said.

The fault is split into four major segments, the researchers found. One begins off of northern California and extends to Cape Blanco, Oregon. The next extends northward from Cape Blanco to Alsea Bay. Here, the researchers saw a lot of slip, or movement of the two sides of the fault against one another. The next segment extends north of Alsea Bay to the mouth of the Columbia River.

Finally, there is a large — and important — segment stretching from southern Washington to southern Vancouver Island. Here, the plates come together at a flat, shallow angle, and there is a lot of area of contact. The size of an earthquake directly scales to the size of the area that ruptures, Carbotte says. This means that the southern Washington to southern Vancouver Island segment is the most likely to give off a major earthquake.

The Cascadia subduction zone last generated a major earthquake in 1700. There are no written records of the event from that time, but drowned trees and a mystery tsunami recorded in Japan reveal that on Jan. 26 of that year, a magnitude 8.7 to 9.2 quake shook the region. Researchers don't know if the 1700 quake was caused by the entire fault rupturing or just one segment.

The new understanding of the fault's geometry should help scientists better map the hazards from the next Cascadia quake, Carbotte said. This includes not only potential shaking along highly populated regions such as Vancouver and Seattle, but also tsunami risk along the coast.

"The segmentation means you can make more informed predictions of how the patterns of shaking might vary," Carbotte said.

The findings were published Friday (June 7) in the journal Science Advances.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.