The oldest rocks on Earth

The world's oldest rocks are spread across the globe and paint a picture of Earth's turbulent early history. Here are some of the most notable and important formations scientists have discovered.

Earth has existed for 4.54 billion years, and during that time, our planet has undergone a number of violent transitions. This makes it difficult for researchers to find out what happened during Earth's early history, as most of the evidence was destroyed eons ago.

However, scientists have discovered ancient rocks scattered throughout the globe. These remnants provide a glimpse into Earth's infancy and help scientists trace our planet's development. Here are some of the oldest rocks ever discovered and the insights they provide about our home planet.

The Jack Hills, 4.4 billion years old

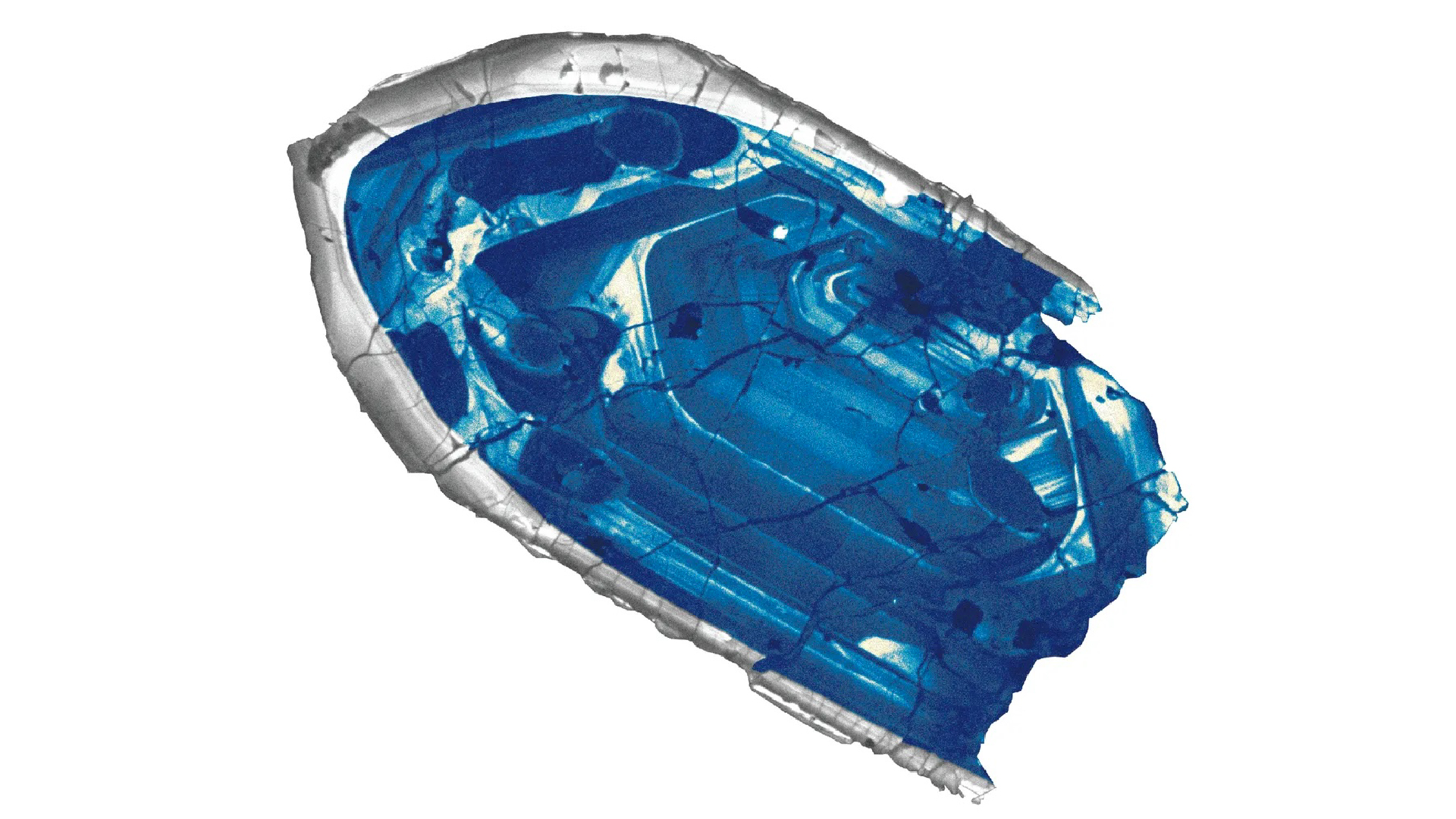

The Jack Hills, in Western Australia, contain tiny traces of rock that are older than the hills themselves. The 50-mile-long (80 kilometers) ridge contains crystallized minerals called zircons dating to 4.4 billion years ago, making them the oldest Earth materials ever found. Zircon crystals are durable; they can survive even when the rocks around them are destroyed, eroded or recycled back into Earth's middle layer. Zircons contain radioactive uranium, which decays very slowly, thereby helping geologists accurately date the crystals. Some zircons in the Jack Hills, which date to around 4 billion years ago, also hint that early Earth had fresh water just 600 million years after it formed.

Nuvvuagittuq Greenstone Belt, 3.8 billion to 4.3 billion years old

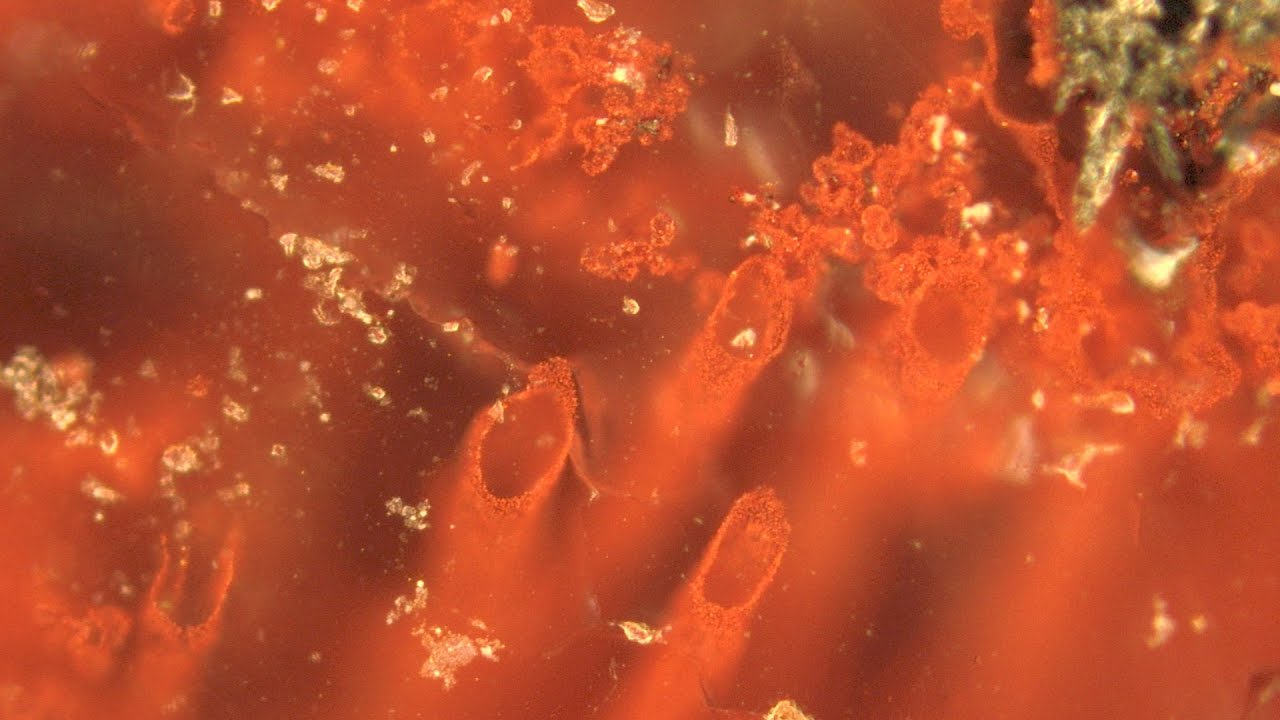

The Nuvvuagittuq Greenstone Belt in northern Quebec may hold the world's oldest preserved rock. A greenstone belt is a long area that mainly contains metamorphosed sedimentary and volcanic rocks and is the remains of an ancient ocean basin. The exact age of Nuvvuagittuq's rocks is controversial: Some studies used zircons to find a minimum age of 3.8 billion years old, but a later study that looked at parts of Earth's primordial crust suggested the rocks' maximum age was 4.3 billion years old, meaning it dates to the Hadean (4.6 billion to 4 billion years ago). Subsequent studies continue to debate the belt's exact age. Some researchers have also suggested the belt contains evidence of Earth's earliest life — traces of bacteria dating to between 4.3 billion and 3.7 billion years ago.

Related: What's the difference between a rock and a mineral?

Acasta Gneiss, 4 billion years old

Rocks located in the Acasta Gneiss Complex in northern Canada have been dated to 4 billion years ago, making them the oldest definitively dated rocks, according to the educational platform Open Geology. Gneiss is a type of metamorphic rock that has been subjected to high temperatures and pressures deep in Earth's crust. The rock was isotopically dated, meaning scientists measured the ratio of uranium atoms that have transformed into lead.

Isua Greenstone Belt, 3.8 billion years old

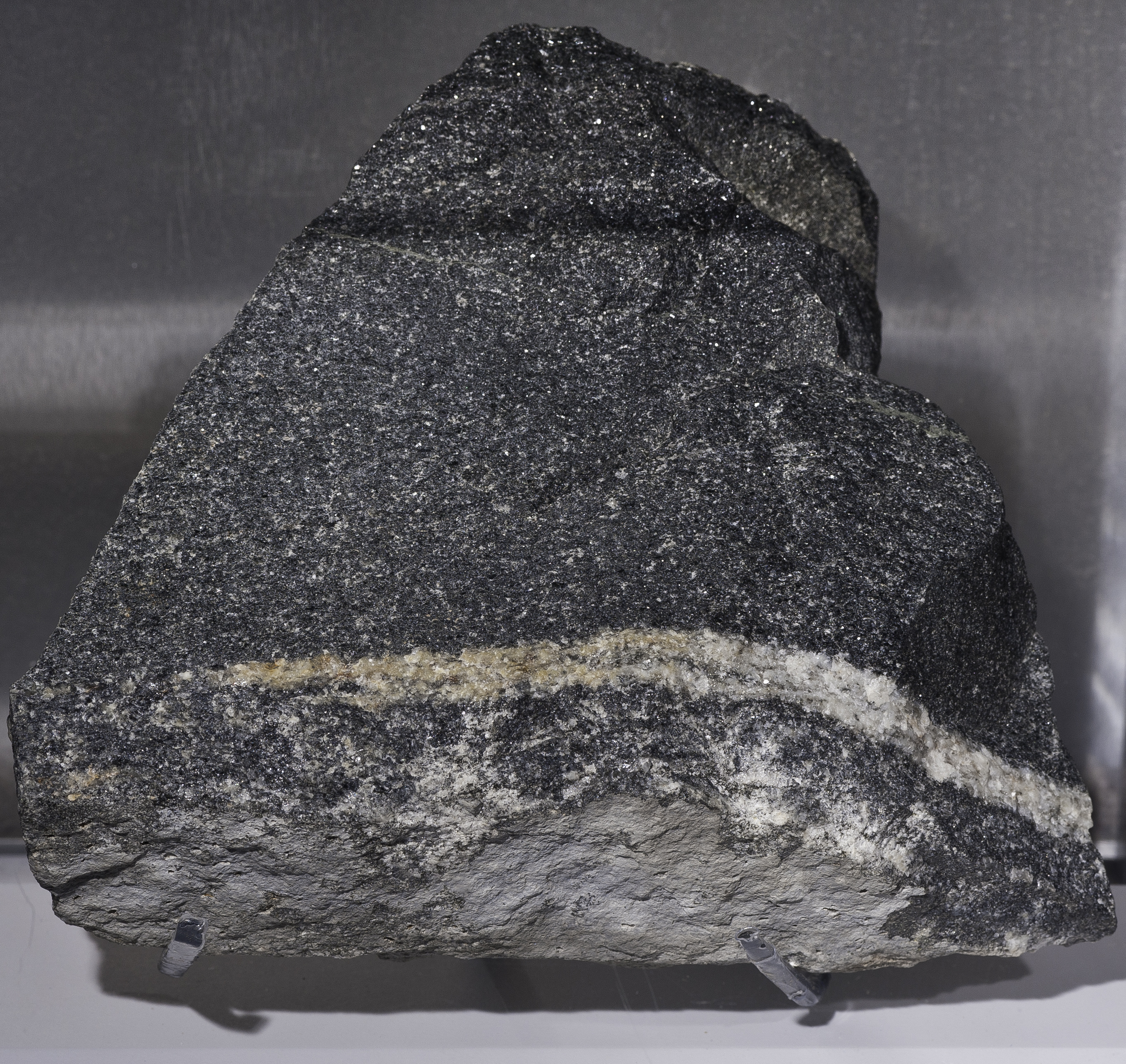

The Isua Greenstone Belt in western Greenland contains some of the oldest rocks on Earth. However, Isua is also important because some researchers have argued it holds the earliest evidence of life on Earth, dating to 3.7 billion years ago. In 2017, researchers discovered what looked like tiny waves in a cross section of the surface of a rock outcrop. The researchers said the ripples are the fossilized remains of cone-shaped stromatolites — layered mounds of sediment and carbonates that build up around colonies of microbes that grow on the floor of shallow seas or lakes. However, this finding is controversial. In addition, Isua holds "chemical fingerprints" of an ancient magma ocean that bubbled over much of Earth's surface 4.5 billion years ago, soon after the planet's birth.

Barberton Greenstone Belt, 3.5 billion to 4.1 billion years old

Ancient rocks in southern Africa's Barberton Greenstone Belt contain evidence for some of the earliest known earthquakes, which occurred around 3.3 billion years ago. The rocks provide evidence of early plate tectonics. In 2021, researchers published a partial map of the belt, which revealed "a gigantic jumble of blocks" detached from where they formed, Simon Lamb, a geologist at Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand who was involved in a later study on Barberton, told Live Science at the time. The belt also contains ancient zircons dating to between 4.1 billion and 3.3 billion years ago.

Napier Complex, 3.6 billion to 4 billion years old

The Napier Complex in eastern Antarctica holds zircons dating to around 3.6 billion years ago and just one zircon dating to 4 billion years ago. "Its significance cannot be overestimated, since it may indirectly evidence the existence of an Early Archean crustal block with a minimum age of 4 Ga [4 billion years]," researchers wrote in a 2011 study of the zircons published in the journal Doklady Earth Sciences. Crustal blocks, also known as fault blocks, are huge chunks of rock formed by tectonic and other forces.

Anshan area, 3.8 billion years old

The Anshan area in northeastern China holds the country's oldest rocks and some of the most ancient rocks in the world. Anshan is part of the 580,000-square-mile (1.5 million square kilometers) North China Craton, but the most ancient rocks cover less than 8 square miles (20 square km).

Big Bertha, 4 billion years old

In 2019, scientists discovered that one of Earth's oldest rocks has spent billions of years away from our planet and only recently returned home. Apollo 14 astronauts collected the roughly 4 billion-year-old rock, nicknamed Big Bertha, from the moon's surface in 1971. The stone contains minerals similar to granite and quartz, which are extremely rare on the moon, study co-author Alexander Nemchin, a professor in the School of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Curtin University in Australia, said in a statement. The 2019 research found that parts of the rock formed in conditions that are rare on the moon but typical on Earth. This finding suggests it formed on Earth but was knocked away from our planet by a giant asteroid impact, before settling on our celestial neighbor, according to NASA.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

James is Live Science’s production editor and is based near London in the U.K. Before joining Live Science, he worked on a number of magazines, including How It Works, History of War and Digital Photographer. He also previously worked in Madrid, Spain, helping to create history and science textbooks and learning resources for schools. He has a bachelor’s degree in English and History from Coventry University.