We're one step closer to finding out why Siberia is riddled with exploding craters

A new physical model suggests meltwater from thawing permafrost on Russia's Yamal Peninsula can unlock methane sources at depth, triggering explosions that open enormous craters at the surface.

Enormous craters in Siberia's permafrost may finally have a decisive explanation. They form when pressurized water causes cracks to form in the permafrost, triggering a sudden, explosive release of methane gas, scientists say.

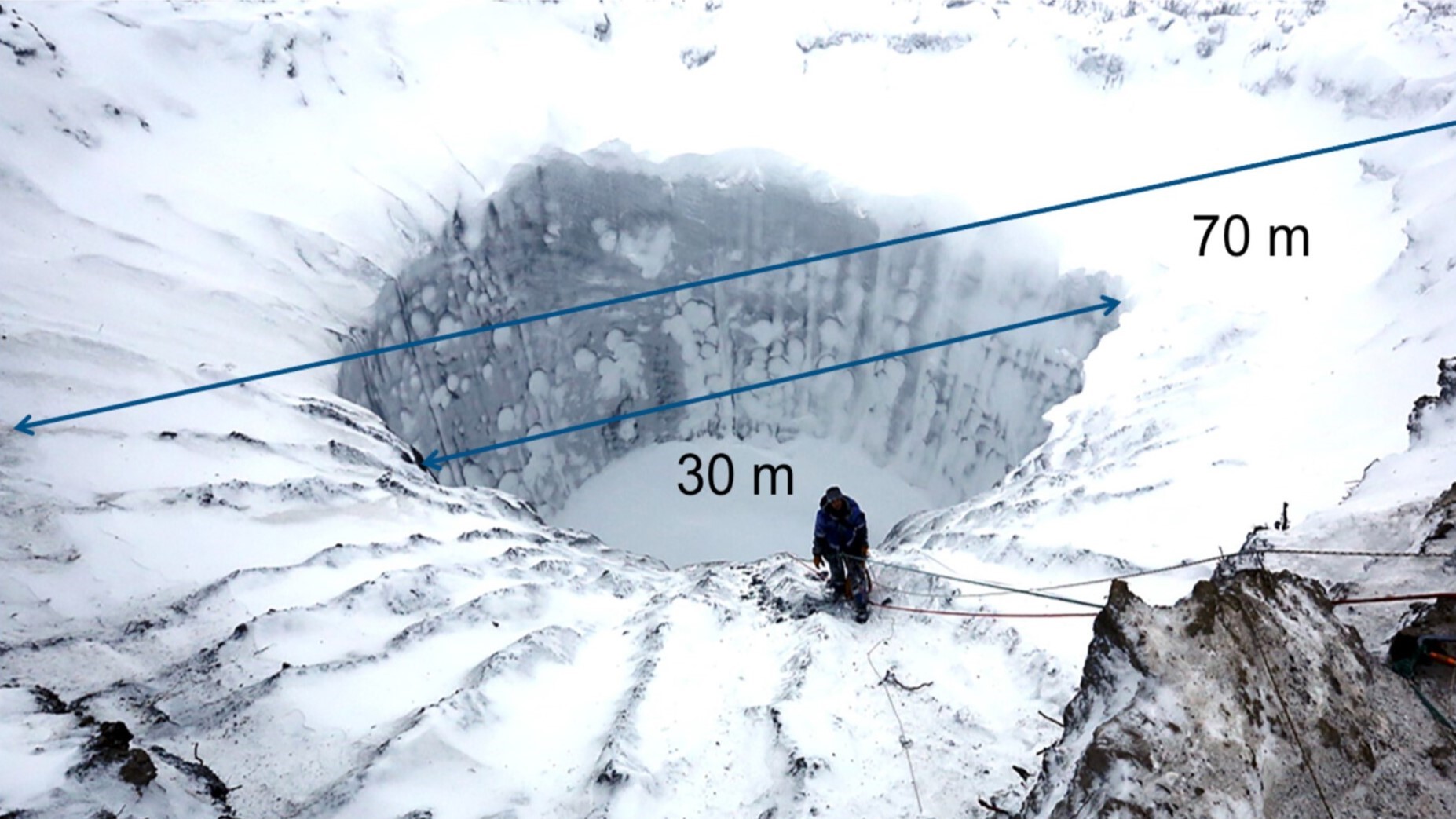

The mysterious craters measure 160 feet (50 meters) deep and up to 230 feet (70 m) across, and first appeared on Russia's northern Yamal and Gydan peninsulas in 2014. Chunks of rock and ice strewn across the landscape around the craters indicated they were caused by giant explosions. These strange craters have never been found elsewhere in the Arctic.

Now, new research may finally explain why these explosions only occur in Siberia.

"These are very, very specific conditions that allow for this phenomenon to happen," study co-author Ana Morgado, a doctoral student and chemical engineer at the University of Cambridge in the U.K., said in a statement. "We're talking about a very niche geological space."

Related: Thawing Arctic permafrost could release radioactive, cancer-causing radon

No matter how niche, the explosions could trigger a climate feedback loop leading to huge releases of the powerful greenhouse gas methane.

"This might be a very infrequently occurring phenomenon," Morgado said. "But the amount of methane that's being released could have quite a big impact on global warming."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Over the past decade, researchers have proposed several factors that may contribute to the Siberian craters' formation, linking them to permafrost thaw and to the breakdown of water-methane crystals, called methane hydrates, into methane gas and water.

"We knew that something was causing the methane hydrate layer to decompose," Morgado said.

To figure out how all these factors were connected, the researchers worked through a series of equations and conducted experiments in the lab that mimicked the permafrost. They determined that the explosions are likely caused by high pressure, similar to how a balloon explodes when it's overinflated. Next, they had to figure out what caused that hyper-pressurization.

"It's a bit like detective work," Morgado said.

The new study pinpoints pockets of salty water in the permafrost called cryopegs, which lie directly above methane hydrate. These cryopegs, found only in northern Russia, are the leftovers of prehistoric seas that disappeared during the last ice age as temperatures dropped, locking water in continent-wide ice sheets. Cryopegs stay liquid despite their icy surroundings due to high pressures and salt content.

Because cryopegs are much saltier than the surrounding permafrost, meltwater from thawing surface permafrost travels down into these pockets to equalize the salt concentrations between the two water reservoirs, according to the study, published Sept. 26 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. This slowly builds pressure inside the cryopegs.

Eventually, the strain becomes so high that cracks form in the permafrost above the cryopegs. This releases the pressure within the permafrost. The methane hydrates immediately below the cryopegs are kept stable by low temperatures and high pressure, so a sudden drop in pressure in these layers may cause methane to split off from the crystals and revert to its gas state, triggering a huge explosion.

These processes likely occur over several decades, which is why explosions resulting in craters are rare, the study authors noted.

Editor's Note: This article was updated Oct. 14, 2024 at 10:00 E.T. to add a map showing the location of Siberia's gas emission craters.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.