Weird blobs lurking near Earth's core may have been dragged from the surface

A new study of seismic data from Antarctica finds that the mantle may be stranger and more variable than previously believed, with pieces of ancient crust that have been dragged down by tectonic forces.

Strange "blobs" deep in Earth's middle layer may be chunks of ancient continental crust that have been dragged down by tectonic forces, new research suggests.

These blobs, known as ultra-low velocity zones (ULVZs), have long puzzled scientists. They're deep in the mantle, near the boundary with Earth's core, so researchers can only glimpse them by studying earthquake waves as they reverberate around the planet's interior like a bell. These waves slow down significantly in the blob regions, which indicates they are different from the mantle around them.

In the new study, published April 17 in the journal JGR Solid Earth, researchers suggest that these regions might be more widespread than previously believed — and that their composition varies dramatically from blob to blob.

"There is more of that material down there," study lead author Samantha Hansen, a geologist at the University of Alabama, told Live Science. "Whatever that material is."

Related: 2 giant blobs in Earth's mantle may explain Africa's weird geology

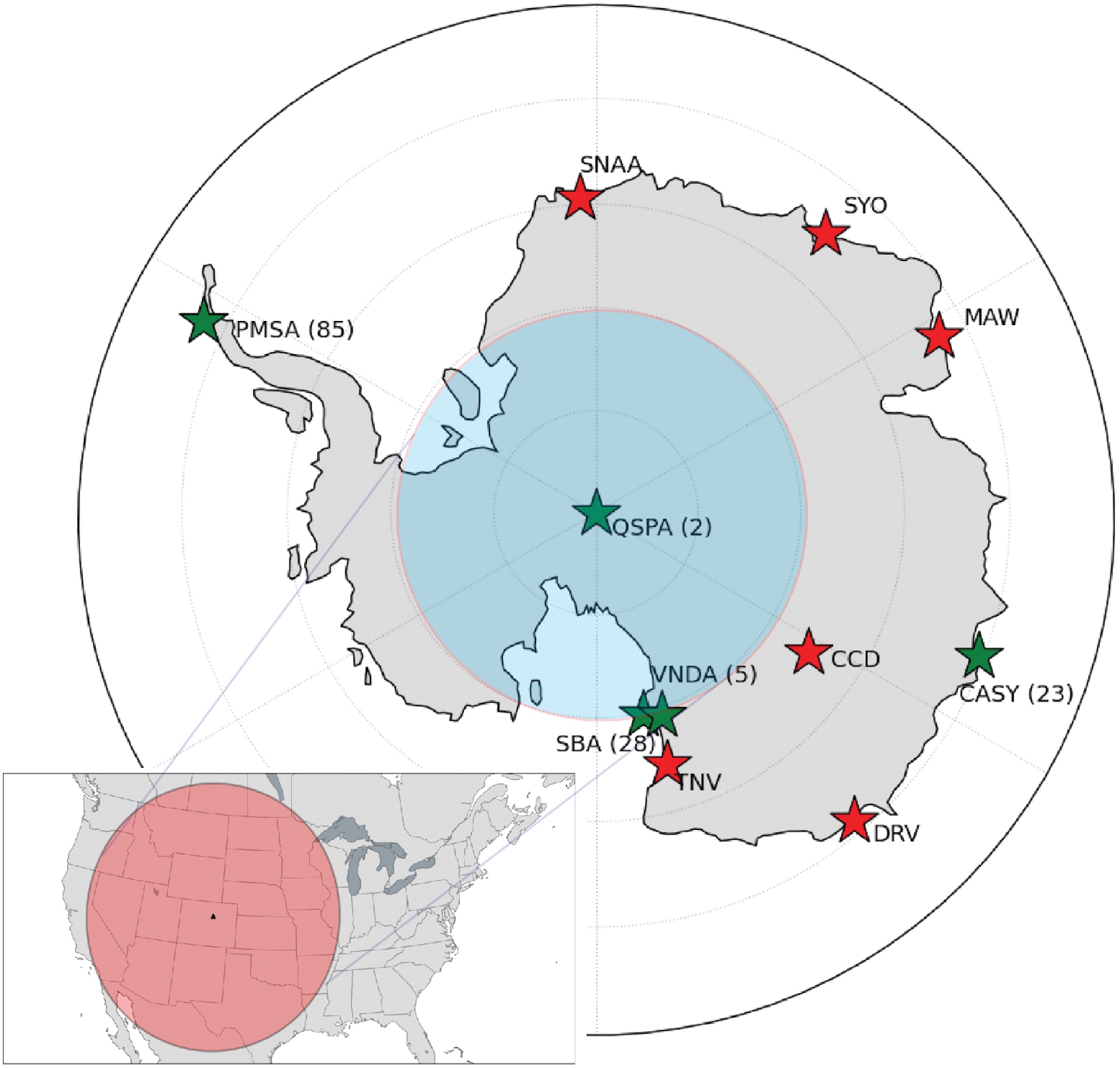

In 2012, Hansen and her team began a project to study the upper mantle via a network of seismic monitors in Antarctica, but they soon realized they had a unique dataset. To image the lower mantle with earthquake waves, scientists need the right combination of earthquake locations and sensors, and Antarctica offered a new window into structures beneath the Southern Hemisphere, she said.

"One of the big advantages of using the Antarctic stations was that it let us examine part of the lowermost mantle that hadn't been looked at before," Hansen said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When the scientists analyzed the data, they found widespread ULVZs in the Southern Hemisphere, the team reported April 17 in the journal JGR Solid Earth. They also modeled global subduction, or the phenomenon of oceanic crust sinking into the mantle. Currently, this occurs in subduction zones such as those around the Pacific "Ring of Fire," where earthquakes and volcanoes are common. The ULVZs seemed to be in the positions that would be expected if they were ancient oceanic crust brought down toward Earth's center by subduction.

"Our best interpretation is that they're related to subducted materials," Hansen said.

There are other hypotheses for ULVZs, including that they are simply mantle regions with temperature variations that cause partial melting, which could change the way earthquake waves move through them. Another hypothesis holds that they're remnants of the planetary collision that created the moon. But subduction might explain why ULVZs are not all created equal, Hansen said.

"You could potentially explain this really wide distribution of ULVZ characteristics that have been reported by the fact that the material is variable itself," she said.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.