What's inside Earth?

The center of Earth lies around 4,000 miles under our feet — but what lies beneath the outer crust and the inner core?

The center of the Earth is almost 4,000 miles (6,400 kilometers) beneath our feet. To put that into context, the deepest humans have ever drilled is 7.6 miles (12.2 km) down, and it took geologists nearly 20 years to get that far, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

Fortunately, scientists don't have to burrow inside our planet to study it. By measuring seismic waves traveling through Earth, researchers have developed a solid understanding of its basic internal structure. So, what's inside Earth?

Planet Earth is broadly composed of a crust, mantle and core. The crust hosts all known life, but it's merely Earth's outer casing, accounting for only 1% of the planet's total volume. The mantle, or middle layer, makes up 84% of Earth's volume, and the innermost layer, the core, makes up the final 15%, according to the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

The crust

The crust is split into oceanic crust and continental crust. The oceanic crust is 3 to 6 miles (5 to 10 km) thick and located beneath the oceans, while the continental crust is up to 50 miles (80 km) thick, according to the Seismin project at University College London.

Related: How does coal form?

The oceanic crust is mostly basalt rock, and it's denser than the continental crust, which is largely granite. So when an oceanic plate collides with a continental plate, the denser oceanic crust travels beneath the continental crust, according to Live Science's sister site Space.com. This process takes a long time but eventually sends oceanic crust down into the mantle at a rate of 1 to 3 inches (2 to 8 centimeters) per year, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

The mantle

The mantle isn't liquid, but it's less rigid than sinking oceanic crust, Sunyoung Park, an assistant professor who studies Earth's internal structure at the University of Chicago, told Live Science. "In geological timescale[s], it's almost acting like a fluid, although it's solid rock," she said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The mantle is made up of different minerals, but bridgmanite is probably the most abundant, Park noted.

This part of Earth runs to a depth of around 1,800 miles (2,900 km), according to the Seismin project, and there's an upper mantle and a lower mantle. Earth's internal temperature increases between the boundary of the upper mantle and the bottom of the lower mantle, ranging from around 1,800 to 6,700 degrees Fahrenheit (1,000 to 3,700 degrees Celsius), according to Space.com.

The core

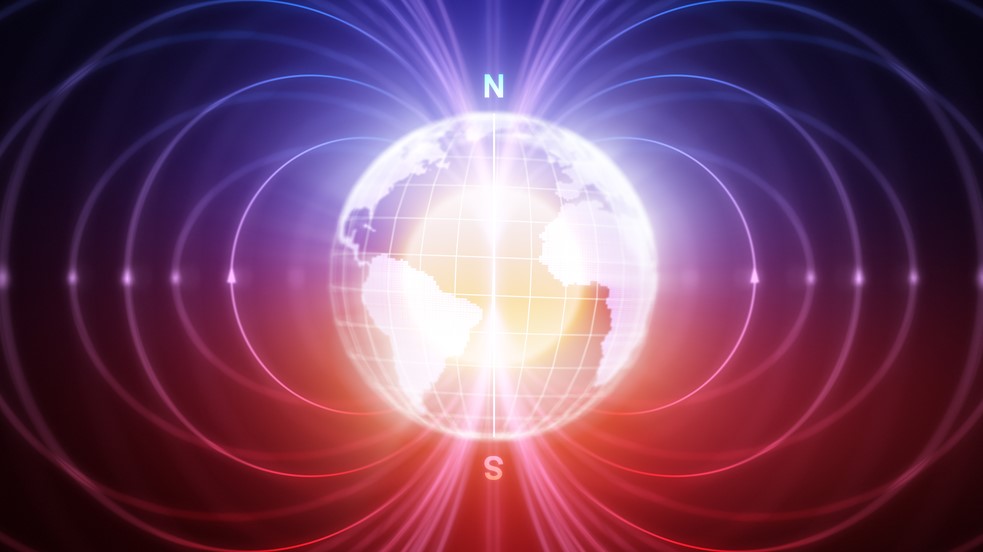

A 1,400-mile-thick (2,300 km) sea of molten iron and nickel marks the beginning of Earth's core. This liquid sea, known as the outer core, surrounds a mostly solid iron ball — around 1,520 miles (2,440 km) wide — called the inner core. The liquid iron outer core swirls around the inner core, giving Earth its magnetic field.

Our planet formed around 4.6 billion years ago, and as it cooled, heavier elements such as iron and nickel migrated inward to create the core. The inside of Earth is still cooling, and as it does so, the inner core continues to form, Park said.

"Just like water becoming ice, iron is getting solidified and becoming [the] inner core, so [the] inner core is actually growing," Park said. But it's growing more slowly than a human fingernail, she added.

The inner core is about 9,400 F (5,200 C) — about as hot as the surface of the sun — but tremendous pressure keeps it mostly solid. Inside the inner core is the innermost core, a 450-mile-wide (725 km) solid metal ball.

Patrick Pester is the trending news writer at Live Science. His work has appeared on other science websites, such as BBC Science Focus and Scientific American. Patrick retrained as a journalist after spending his early career working in zoos and wildlife conservation. He was awarded the Master's Excellence Scholarship to study at Cardiff University where he completed a master's degree in international journalism. He also has a second master's degree in biodiversity, evolution and conservation in action from Middlesex University London. When he isn't writing news, Patrick investigates the sale of human remains.