'Imagine a lush tropical island slipping beneath the waves': Drowned island the size of Iceland found off Brazil

An undersea volcanic plateau in the southwestern Atlantic was a tropical island 45 million years ago.

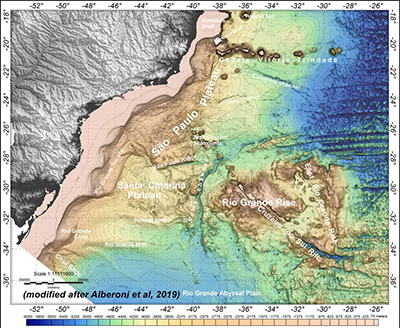

In 2018, Brazilian and British scientists were exploring the seafloor around a volcanic plateau known as the Rio Grande Rise when they spotted rocks that looked like they belonged on dry land.

Watching video relayed from their remotely operated submersible 650 meters (2,100 feet) below the surface, unusual red clay layers caught their attention. "You just don't find red clay on the seabed," said Bramley Murton, a marine geologist from the National Oceanographic Centre in Southampton, U.K., who was on the expedition. "The deposits looked like tropical soils," he explained.

In a recent study, the team showed that the clay's distinctive mineral makeup could have formed only by open-air weathering in tropical heat and humidity. It's the latest in a string of discoveries hinting that this patch of ocean, 1,200 kilometers (750 miles) from Brazil's coast, was once an island.

Volcanic origins

"Imagine a lush tropical island slipping beneath the waves and lying frozen in time. That's what we've uncovered," said Murton, who coauthored the study. He and colleagues think the island would have been similar in size to Iceland (about a fifth of the Rio Grande Rise's total area).

The origins of the Rio Grande Rise go back 80 million years. An enormous mantle plume sat beneath the South Atlantic's mid-ocean ridge, causing a burst of intense volcanism; the resulting rise "started life as a Cretaceous version of Iceland" closer to the mid-ocean ridge than what is now South America, Murton said. Gradually, as volcanic activity subdued, the volcanic plateau drifted west across the Atlantic and sunk beneath the waves.

But starting around 40 million years ago, the mantle plume had one last gasp of volcanism, this time isolated to the western portion of the rise. And it's in this area that the researchers found the red clays, sandwiched between lavas known to be about 45 million years old.

"This is an outstanding result," said Luigi Jovane, a marine geologist from the University of São Paulo and coauthor of the study. "The red clays are conclusive proof that this was once an island." Jovane has been leading investigations in the Rio Grande Rise for more than a decade.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Underwater Exploration

The research is the culmination of two scientific expeditions to the rise in 2018. The first, aboard the Brazilian research vessel Alpha Crucis, mapped the rise's underwater terrain using sonar. That project was initially aimed at characterizing mineral-rich ferromanganese crusts known to occur on the seafloor of the rise.

The researchers' mapping revealed a steep-sided, 30-kilometer-long (20-mile-long) canyon bisecting the rise — the Cruzeiro do Sul Rift — as well as ancient beach terraces, wave-cut platforms, and drowned waterfalls.

Eight months later, the team returned aboard the National Oceanography Centre's RRS Discovery. That vessel is equipped with a remotely operated vehicle (ROV), which allowed them to capture footage of rocks exposed in the steep-sided canyon walls. The ROV also has a robotic arm for collecting samples.

Most investigations of seabed geology rely on sonar mapping and dredging for rock samples, said Tony Watts, a marine geologist from the University of Oxford who was not involved in the study. But "by using an ROV, [the researchers] could be more confident about the location and context of the red beds."

Armed with a sample of the red clay, the researchers measured its mineral composition back in the lab. They found that it mostly contained a type of clay mineral called kaolinite, which dominates tropical soils because it is resistant to extreme chemical weathering.

"These red clays are exactly the same, chemically and mineralogically, as the red earth or terra roxa we find all over Brazil," Jovane said. "We are confident that they represent the in situ, weathered upper surfaces of the lavas."

"This is a robust dataset," said Watts, who agreed with the team's interpretation that this area was once above sea level. He added that the research has important implications for understanding the magmatic and subsidence history of the rise.

Evidence collected in the 1980s, including drill cores containing shallow-water microfossils, had indicated the western part of the rise was uplifted during the Eocene, Murton said. But "no one has found convincing evidence for subaerial volcanism and exposure of the western rise until now."

Coveted minerals

The Rio Grande Rise is more than just scientifically fascinating. It also has potential economic value owing to its ferromanganese crusts. In December 2018, the Brazilian government applied to the United Nations to extend its maritime borders to include the Rio Grande Rise.

The rise is located in international waters and is well beyond Brazil's 370-kilometer-wide (200-nautical-mile wide) exclusive economic zone — where coastal nations have sovereignty over seabed resources. To qualify for an extension, Brazil needs to prove that the rise has the same geological characteristics as the nation.

The rise's newfound status might help bolster that ongoing claim. "The Rio Grande Rise and the continent have the same soil and climate," explained Jovane. "In that sense there is a direct relationship between the two."

Jovane said Brazil needs to prove not only that it has a correct claim to the Rio Grande Rise but that it can mine the area sustainably. Currently, Brazil has regulations for mining only on land, and there is still no legislation for seabed mining in international waters.

This article was originally published on Eos.org. Read the original article.

Eos is the award-winning science news magazine published by AGU.