Bizarre, never-before-seen viruses discovered thriving throughout the world's oceans

The discovery of a strange group of viruses, dubbed mirusviruses, that infect ocean plankton across the globe may shed light on the origin of herpes.

Scientists have discovered never-before-seen viruses that thrive in sunlit oceans from pole to pole and infect plankton. They dubbed the newfound microbes "mirusviruses" — "mirus" meaning "strange" in Latin.

The researchers concluded that mirusviruses belong to a large group of viruses called Duplodnaviria, which includes the herpesviruses that infect animals and humans, based on shared genes that encode the shell, or "particle" enclosing their DNA. But the strange, newfound viruses also share a staggering number of genes with a group of giant viruses, called Varidnaviria.

This suggests that mirusviruses are a bizarre hybrid between two distantly related viral lineages, the scientists concluded.

"They seem to be an extremely unusual group of viruses," Tom Delmont, a researcher at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) who participated in the discovery, told Live Science. "This is why we consider them as being chimeric, because they are a mix of two different groups of viruses — on one side the herpesviruses, based on the particle genes, and on the other side the giant viruses, based on many more genes."

The team described the strange, newfound viruses in a study published Wednesday (April 19) in the journal Nature. The discovery highlights how little we know about the viruses lurking in Earth's oceans.

Related: Scientists discover viruses that secretly rule the world's oceans

To find the viruses, the team pored over data from the Tara Ocean expedition, which collected nearly 35,000 ocean water samples containing viruses, algae and plankton between 2009 and 2013. The researchers then searched for evolutionary clues in millions of microbes' genes.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Working on this data is like surveying a huge area of sand with a metal detector, looking for a treasure," Delmont said. "We found an evolutionary treasure."

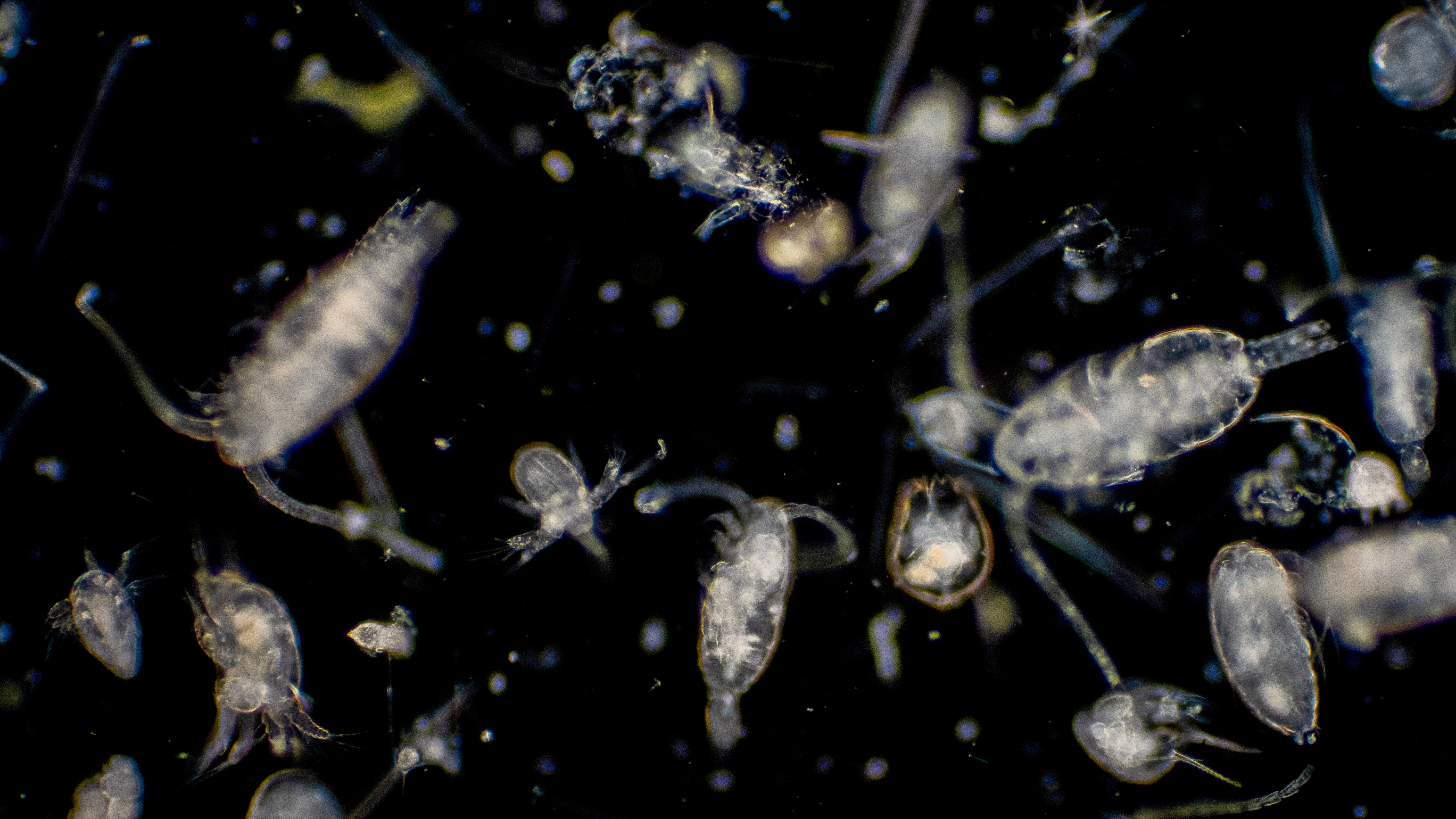

In combing through this data trove, the scientists detected a previously undescribed lineage of double-stranded DNA viruses, the mirusviruses, that can be found in the sunlit surface waters of polar, temperate and tropical oceans. These abundant viruses infect plankton, which are tiny organisms that drift on ocean currents and can produce spectacular blooms visible from space, according to the National Ocean Service.

By invading the plankton's cells, mirusviruses likely help regulate the microorganisms' activity and thus the flow of carbon and nutrients through the ocean.

"Viruses are a very natural component of plankton at the surface of the ocean," Delmont said. "They are going to destroy many, many cells every day and this is going to release nutrients, particles inside the cells that are going to be used by other cells to be active and healthy."

Mirusviruses may be the key to resolving the enigmatic origin of herpes viruses, Delmont said. The genes encoding the protective shell around viral DNA are strikingly similar in both groups, suggesting that they are related.

"This means that there is a shared evolutionary history between herpes, that infect only animals, and the mirusviruses that are everywhere in the ocean, where they infect unicellular organisms," Delmont said. "All of this is pointing to a planktonic origin for herpes."

These unusual viruses represent a new front for research into microbial life in our oceans and there are many more discoveries in store, Delmont said.

"We will be trying to isolate mirusviruses in the coming year," co-author Hiroyuki Ogata, a professor at the Institute for Chemical Research at Kyoto University, told Live Science in an email. "Isolation is now essential to uncover the mystery of this new viral [group]."

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.