390 million-year-old fossilized forest is the oldest ever discovered

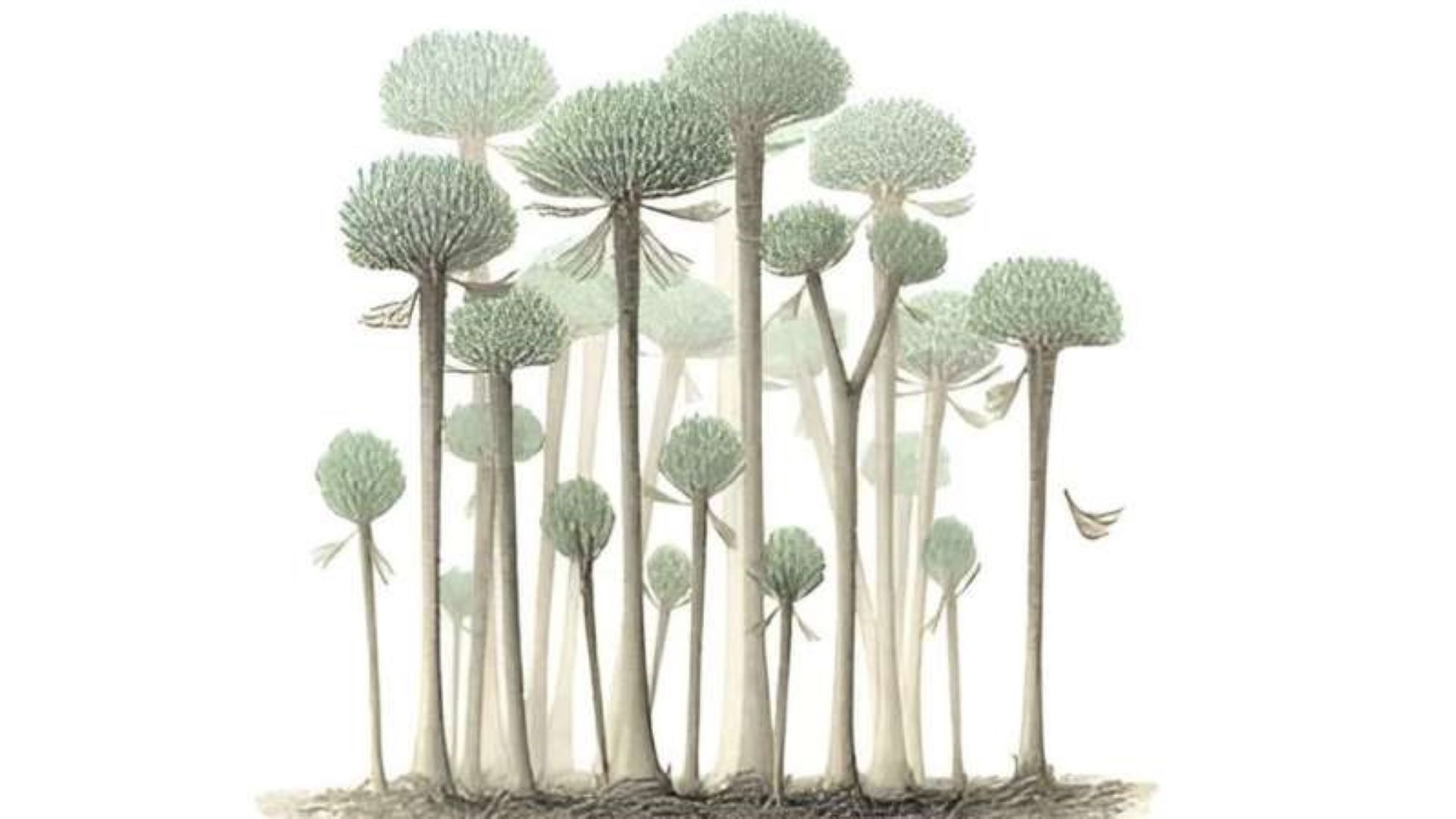

Researchers have discovered a fossil forest with small, palm-like trees and arthropod tracks dating back to the Middle Devonian.

Fossilized trees discovered by chance in southwest England belong to Earth's earliest-known forest, new research has found. The 390 million-year-old fossils supplant the Gilboa fossil forest in New York state, which dates back 386 million years, as the world's oldest known forest.

The new discovery highlights differences between the two ecosystems, suggesting forests went from being relatively primitive to well established over the course of just a few million years, said Neil Davies, the lead author of a new study published Feb. 23 in the Journal of the Geological Society.

"Why it's important — broadly — is it ticks the boxes of being the oldest fossil forest," Davies, a professor in the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Cambridge in the U.K., told Live Science. The finding is also remarkable because it reveals stark differences between the complex array of ancient plants found at Gilboa and the newly discovered forest, which appears to have hosted just one type of plant, Davies said.

This now-extinct type of plants, known as cladoxylopsids, is thought to be closely related to ferns and sphenopsids (horsetails). "They look like palm trees, but they're in no way related to palm trees," Davies said. "They've got a long central stem and what look like palm fronds coming off, but those palm fronds aren't really leaves — they're actually just lots of twiglets."

Related: 'Living fossil' tree frozen in time for 66 million years being planted in secret locations

These twig-crowned trees would have stood between around 6.5 and 13 feet (2 to 4 meters) high, meaning "it wouldn't have been a very tall forest," Davies said.

The fossil trees were preserved both as hollow trunks filled with sediment and as fallen logs that were flattened over the eons — like "casts inside the sediment," Davies said. Little scars where branches used to attach to the trees are still visible, he added.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Davies and his colleagues stumbled upon the forest remnants during fieldwork in the Hangman Sandstone Formation, which dates to the Middle Devonian period (393 million to 383 million years ago). During the Devonian period, what is now the U.K. formed part of a continent called Laurentia that sat just below the equator, meaning the climate was warm and dry, Davies said.

"When I first saw pictures of the tree trunks I immediately knew what they were, based on 30 years of studying this type of tree worldwide," study co-author Christopher Berry, a paleobotanist and senior lecturer at the University of Cardiff in the U.K., said in a statement. "It was amazing to see them so near to home. But the most revealing insight comes from seeing, for the first time, these trees in the positions where they grew."

Older trees exist elsewhere in the world, with plants first colonizing land 500 million years ago, but this new discovery is the earliest example of a forest with trees growing close together and en masse.

"We've found rocks where you've got standing trees in growth positions adjacent to each other over a set area," Davies said, "so we're looking at a snapshot where we can tell for definite that there were trees growing in that specific location and that the sediment we're looking at is the forest floor."

Among the fossil trees, the researchers found trackways belonging to small Devonian critters. "At this time, there's nothing much bigger than lots of little arthropods knocking around on land," Davies said. "You might find some more amphibian-type things and fish in some of the lakes and rivers nearby."

While the researchers had initially set out to examine sediments, the fortuitous discovery of fossil trees may reveal a turning point in Devonian plant ecology. "It kind of suggests that around 390 million years ago, there is this sudden takeoff in forest-type environments," Davies said.

Editor's note: This article was updated at 08:20 E.T. on March 8th to include comments from co-author Christopher Berry and an illustration of the fossilized forest.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.