Fossils from lush 53 million-year-old South Pole rainforest discovered in Tasmania

Researchers have identified 12 ancestral plant species from an early Eocene fossil assemblage in Tasmania that once formed part of a giant, circumpolar forest.

Fifty million years ago, lush rainforests blanketed modern-day Antarctica, Australia, New Zealand and the tip of South America. Now, researchers have discovered new fossils that reveal which plant species populated these forests and how they adapted to life near the South Pole.

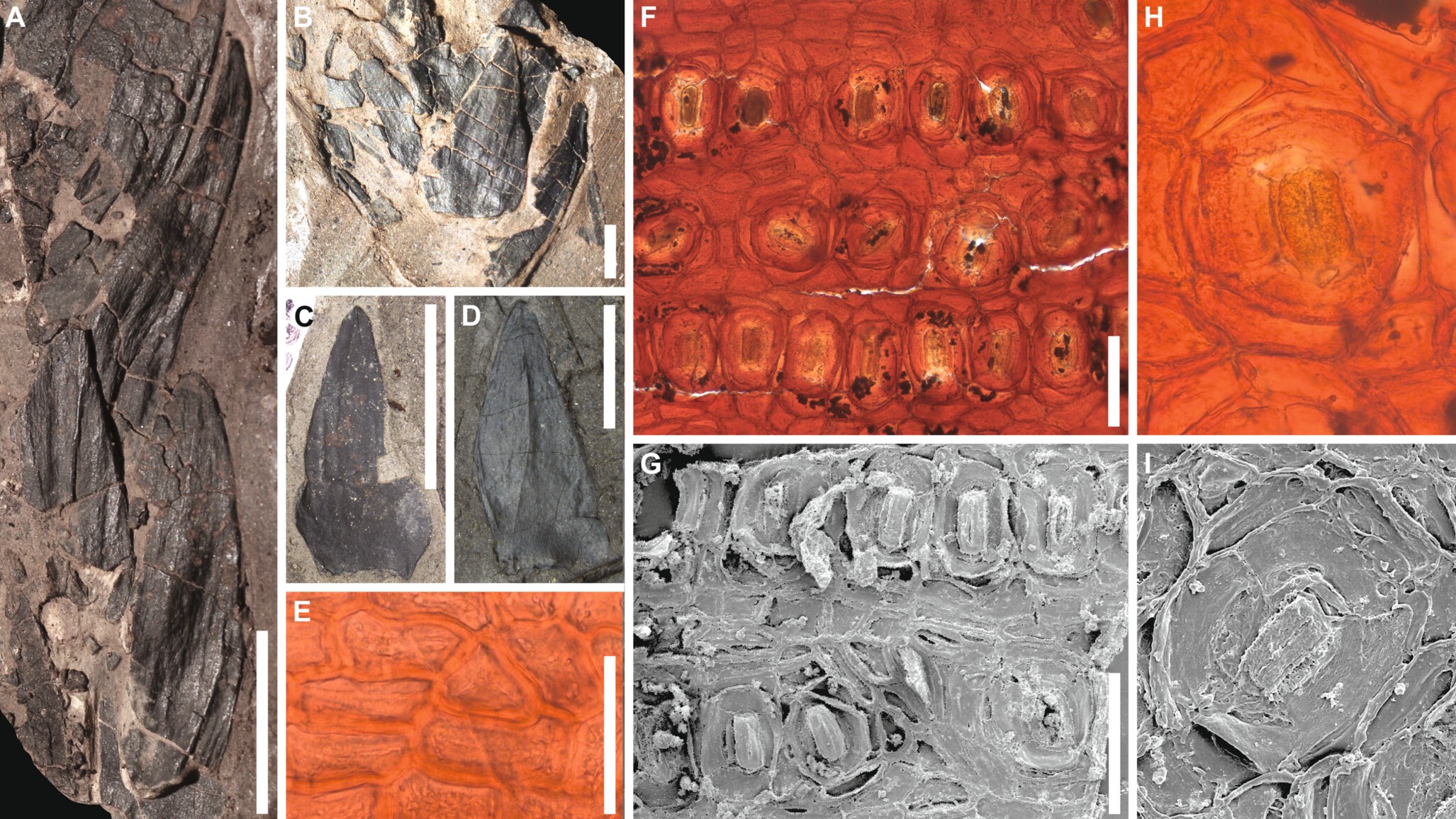

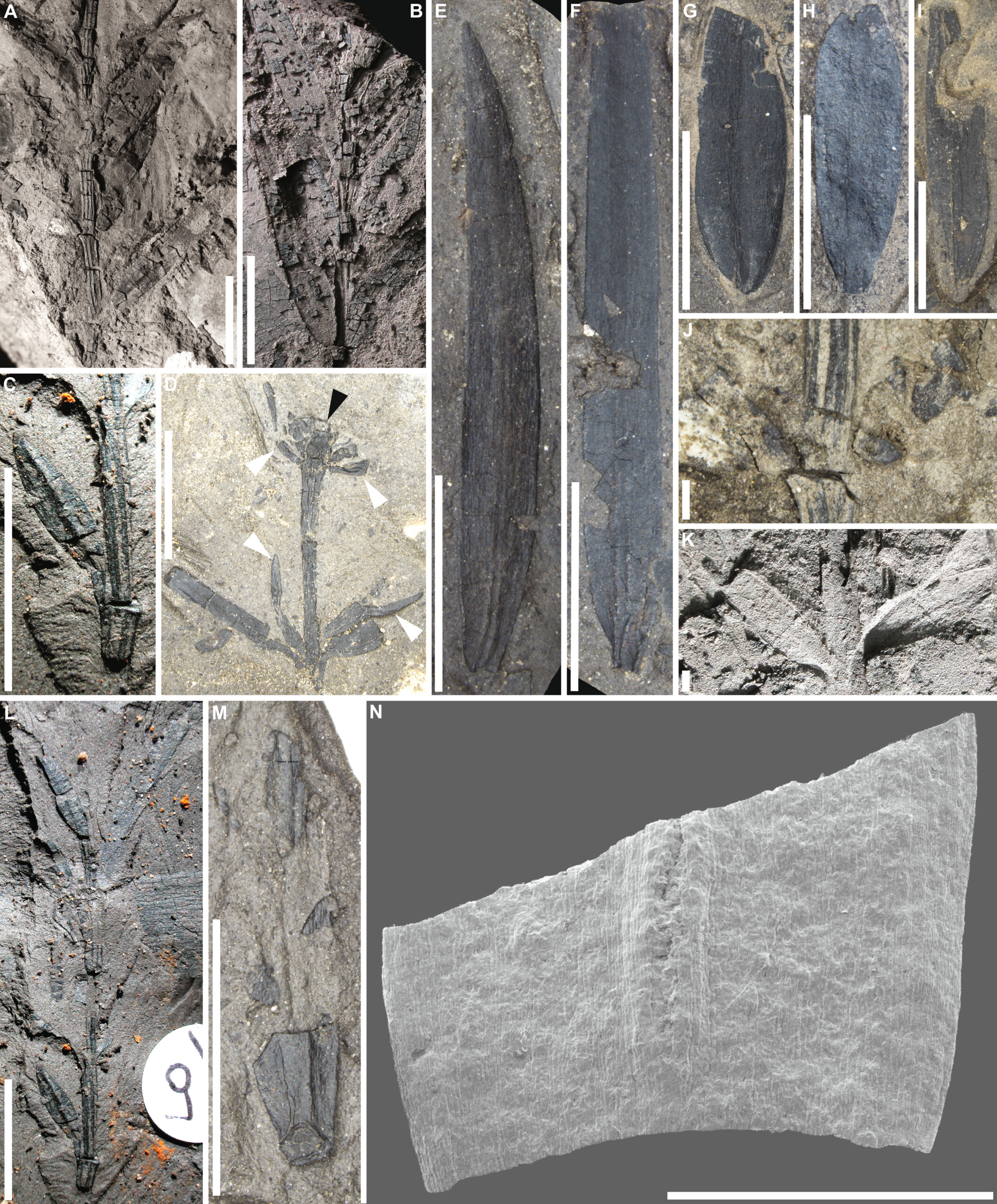

Recent excavations in western Tasmania uncovered a number of plant fossils, including the remains of two species of conifer previously unknown to science that were part of a 53 million-year-old "polar forest."

The forest thrived during the Eocene epoch (56 million to 33.9 million years ago), when global surface temperatures averaged 80 degrees Fahrenheit (27 degrees Celsius) and the southern continents formed one giant landmass around the South Pole, according to a study published Aug. 27 in the American Journal of Botany.

"This discovery offers rare insights into a time when global temperatures were much higher than today," study author Miriam Slodownik, a paleobotanist and recent doctoral graduate from the University of Adelaide in Australia, said in a statement. "Tasmania was much closer to the South Pole, but the warm global climate allowed lush forests to thrive in these regions."

Global temperatures spiked during the Early Eocene Climatic Optimum (53 million to 49 million years ago), a period predating the breakup of Australia from Antarctica between 45 million and 35 million years ago. New fossils unearthed near Tasmania's Macquarie Harbor suggest tropical plants from the polar forest traveled north as the continents drifted apart, seeding rainforests that still exist today.

Related: 390 million-year-old fossilized forest is the oldest ever discovered

Researchers excavated more than 400 plant fossils and analyzed them in the lab using advanced microscopes and ultraviolet photography. These techniques revealed well-preserved leaves and cellular structures that helped the team identify 12 different plant species. Most of these were ancestors of flora still found today in Australia, New Zealand and South America, according to the statement. These three landmasses stayed joined together after the breakup of the ancient supercontinent Gondwana and remained so until at least 49 million years ago.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Of the 12 species, at least nine were conifers, according to the study. "The most spectacular fossils are relatives of the Kauri [Agathis], Bunja [Araucaria bidwillii] and Wollemi [Wollemia nobilis] pines that give clues about the evolution of these iconic Australian trees," Slodownik said.

The researchers, in collaboration with the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre, also identified ferns, a cycad and two newfound, extinct tree species, which they named Podocarpus paralungatikensis and Araucaria timkarikensis. "Paralungatik" is the original name of Macquarie Harbor and "Timkarik" that of the surrounding area in the Aboriginal language of Tasmania, according to the statement.

The analyses revealed that the fossilized plants adapted to the polar environment, which would have experienced the same extreme seasonal light regime 53 million years ago as it does today. The plants evolved large leaves to maximize light absorption in the summer and deciduousness to preserve resources in low-light conditions during the winter, according to the study.

"The analyses showed how these plants adapted and thrived across the Southern Hemisphere in warm, ice-free conditions, even with the extreme seasonal changes near the polar circle," Slodownik said.

But the new fossils reveal details of even wider changes. "These plants tell the story of big changes in climate and the shifting tectonic plates over millions of years," Soldownik said.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.