'Gossiping neighbors': Plants didn't evolve to be kind to each other, study finds

Rather than helping each other out when they're attacked, plants may have to eavesdrop on each other to know when to launch their own defenses.

Rather than warning each other of impending doom, plants may be better off hiding signs of distress from each other, or even lying about danger that isn't there, according to a new study.

"Plants can gain a benefit from dishonest signaling because it harms their local competitors, by tricking them into investing in costly herbivore defence mechanisms," lead author Thomas Scott, an evolutionary theoretician at the University of Oxford, said in a statement. "Our results indicate that it is more likely that plants will behave deceptively toward their neighbours, rather than altruistically."

Previous research shows that if another plant is being attacked by a herbivore or disease, neighboring plants may upregulate their defense responses, which can include producing chemical compounds that make the plant poisonous or unpalatable to herbivores or insects. These defenses are rather energetically costly for the plant to perform, so they won't put them up unless they are absolutely necessary.

However, supporting their neighbors doesn't make sense from an evolutionary perspective as plants are constantly competing with each other for sunlight and nutrients.

For a study published Jan. 21 in the journal PNAS, researchers modeled the evolutionary plausibility of plants acting altruistically, and compared this with the likelihood of these signals being sent for other reasons. Their mathematical models looked at different hypothetical scenarios to look for situations that would lead them to warn neighbors of an attack.

Related: Lost biblical tree resurrected from 1,000-year-old mystery seed found in the Judaean Desert

The researchers found that it is much more evolutionarily advantageous for plants to lie about an attack, sending signals of distress even when nothing is wrong and tricking their neighbors into wasting precious resources.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

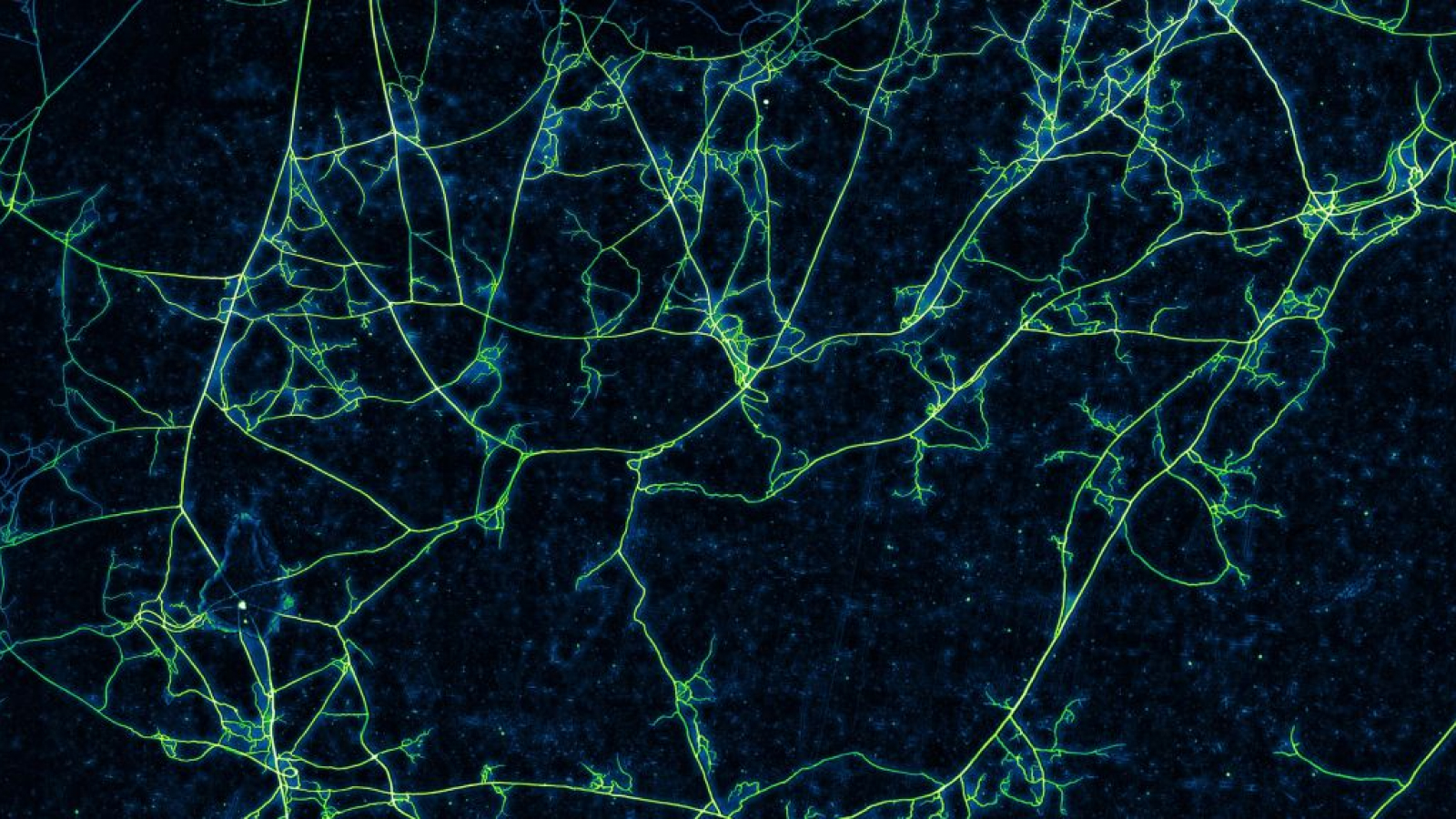

Plants can communicate via a vast underground fungal network connecting their roots, known as the mycorrhizal network — sometimes referred to as the "wood wide web." Between 80% and 90% of all plant species are connected to a mycorrhizal network, according to the scientific research organization Society for the Protection of Underground Networks (SPUN).

These fungi form symbiotic partnerships with plant roots, with the plants receiving nutrients and the fungi receiving food made by the plants from photosynthesis. Information about plant resources can be transmitted through these networks, according to the statement.

The team suggests two possibilities for why the previously observed distress signals from plants may have occurred. The first is that plants release an involuntary signal that they cannot suppress — like a blush in humans — that the nearby plants eavesdrop on. "Maybe just like gossiping neighbours, one plant is simply eavesdropping on the [other]," study co-author Toby Kiers, evolutionary biologist at Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam and executive director of SPUN, said in the statement.

Alternatively, the fungi in the mycorrhizal network may communicate an attack to other plants nearby, as it benefits the network if all plants are protected.

"Mycorrhizal fungi rely on the plants on their network for carbohydrates, so it's important to keep these plants in good condition," Scott said.

"It could be beneficial for fungi to monitor their plant partners, to detect when one plant has been attacked, and then warn the other plants to prepare themselves," he added in an email to Live Science. "This could be beneficial for fungi because it helps them to protect their plant partners from herbivores and pathogens."

Jess Thomson is a freelance journalist. She previously worked as a science reporter for Newsweek, and has also written for publications including VICE, The Guardian, The Cut, and Inverse. Jess holds a Biological Sciences degree from the University of Oxford, where she specialised in animal behavior and ecology.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.