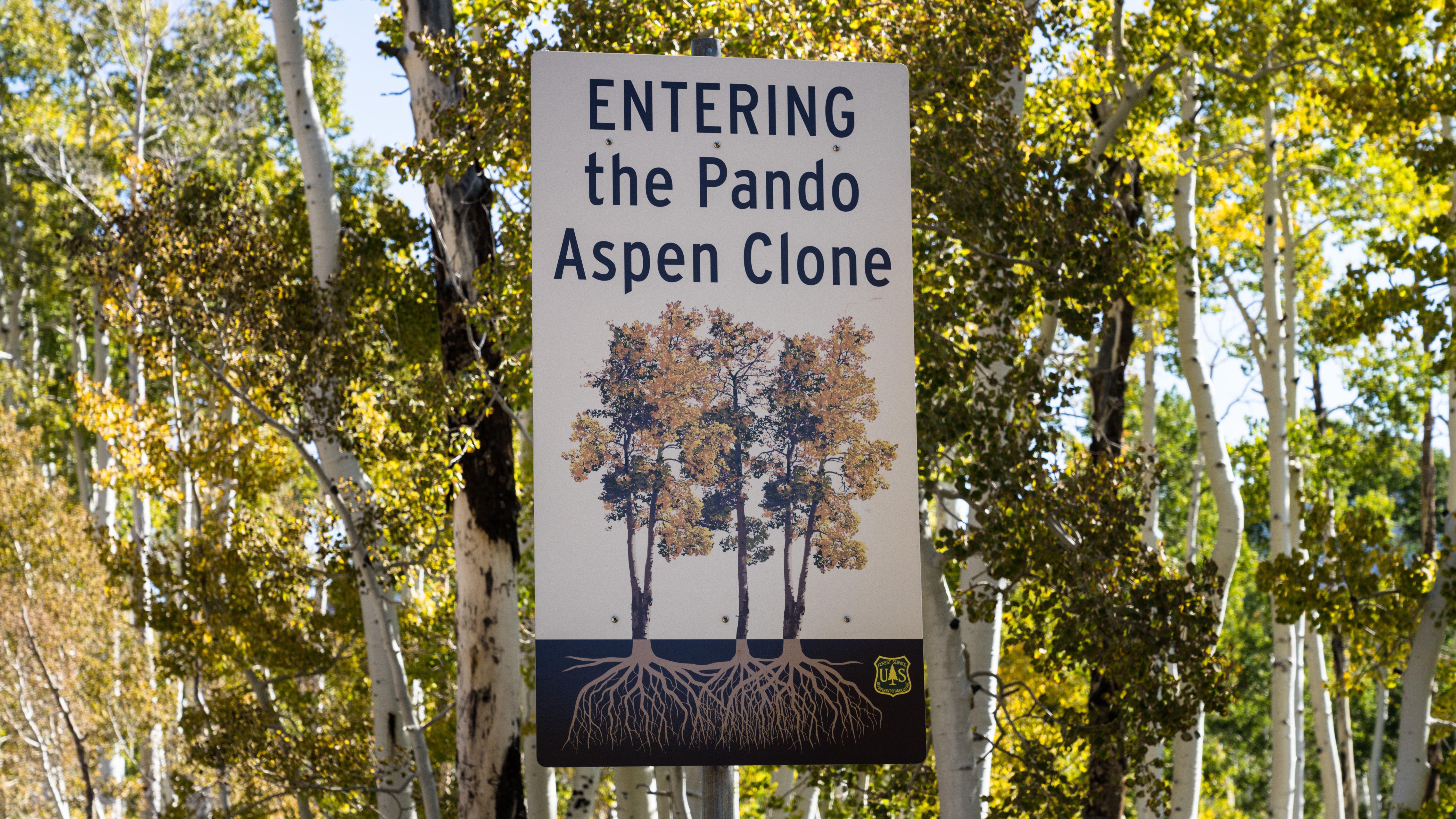

Pando: The world's largest tree and heaviest living organism

Pando is a giant aspen clone in central Utah that has been regrowing parts of itself for up to 80,000 years — but new threats mean the plant is now in decline.

Name: Pando

Location: Fishlake National Forest, Utah

Coordinates: 38.52444764419252, -111.75068313176233

Why it's incredible: Pando looks like a forest, but it's actually one giant tree.

Pando is an ancient quaking aspen tree (Populus tremuloides) with 47,000 genetically identical stems, or tree trunks, connected to a vast underground root system. Each stem is a clone of the one next to it and originates from a single seed that started growing up to 80,000 years ago during the last ice age.

Pando — Latin for "I spread" — is the largest known tree on Earth and the heaviest living organism on record. The colony extends over 106 acres (43 hectares) and weighs an estimated 6,500 tons (5,900 metric tons), which is equivalent to 40 blue whales or three times the world's largest single-stem tree — California's General Sherman giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum).

Related: Listen to the sounds of Pando, the largest living tree in the world

Researchers realized that Pando is a single organism in the 1970s, and geneticists have since confirmed that what looks to the untrained eye like a forest is actually one giant clone, according to the U.S. Forest Service. A recent DNA analysis of hundreds of tree samples suggested Pando is between 16,000 and 80,000 years old, making it one of the oldest living organisms in the world — although that research, which was published Oct. 24, 2024 to the preprint database bioRxiv, has not yet been peer reviewed.

Some of Pando's stems are more than 130 years old, according to the Forest Service, and the plant should continuously regenerate the parts of itself that wither and die. But that hasn't been the case in recent years.

Pando reproduces asexually, creating clones of itself rather than mixing its DNA with that of other trees. The root system produces genetically identical shoots that grow upward, filling in the gaps between stems and keeping the plant alive for thousands of years. But according to a 2018 study, aerial images taken of Pando over a period of 72 years show stark signs of decline, including larger gaps in the canopy and aging stems that aren't being replaced by younger ones.

"Imagine walking into a town of 50,000 people where everybody in town was 85 years old," Paul Rogers, an adjunct associate professor of ecology at Utah State University and director of the Western Aspen Alliance, told National Geographic in 2022. "That's sort of the issue with Pando."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The main culprits for this decline are animals that eat aspen shoots, according to the 2018 study. Mule deer and cattle that graze in Utah's Fishlake National Forest are chomping off the tops of saplings and killing new growth quicker than the plant can compensate for. Wolves, bears and cougars used to keep the deer population in check, but humans have now eliminated most of these predators.

Pests and diseases are also attacking Pando, with root rot as well bacterial and fungal infections affecting the stems, according to the Forest Service. "Another thought is that the Pando is just old and doesn't have the energy reserves to send up suckering [fresh new shoots]," Kurt Robins, a district ranger of Fishlake National Forest, said in a video.

Aspen stands like Pando support highly diverse animal and plant communities and form an integral part of the ecosystem. "We look at the aspen as a keystone species for what they provide on the landscape," Robins said.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.