World's loneliest tree species can't reproduce without a mate. So AI is looking for one hidden in the forests of South Africa.

A single specimen of an ancient tree species was found in 1895. Now scientists are using AI to find it a mate.

The world's loneliest tree may soon find a mate, thanks to artificial intelligence (AI).

Only a single, male specimen of the Wood's cycad (Encephalartos woodii) has ever been discovered in the wild. In 1895, botanist John Medley Wood found the solitary plant in what is now the Ngoye Forest Reserve in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.

Cycads, a primitive type of seed plant, first emerged around 300 million years ago, before dinosaurs roamed Earth. In cycads, male and female reproductive structures — called cones — are produced by separate plants.

However, E. woodii also reproduces via offshoots, meaning that the parent plant sends out shoots that turn into other adult plants. In the 20th century, botanists removed some of the offshoots and transplanted some of the original trunks from the lonely male in South Africa. These have given rise to about 500 separate plants that live in botanical gardens around the world.

However, sexual reproduction is necessary for the long term viability of the species. To help the male offshoots find mates, scientists have launched a series of drone flights over the cycad's remote and inaccessible native forests.

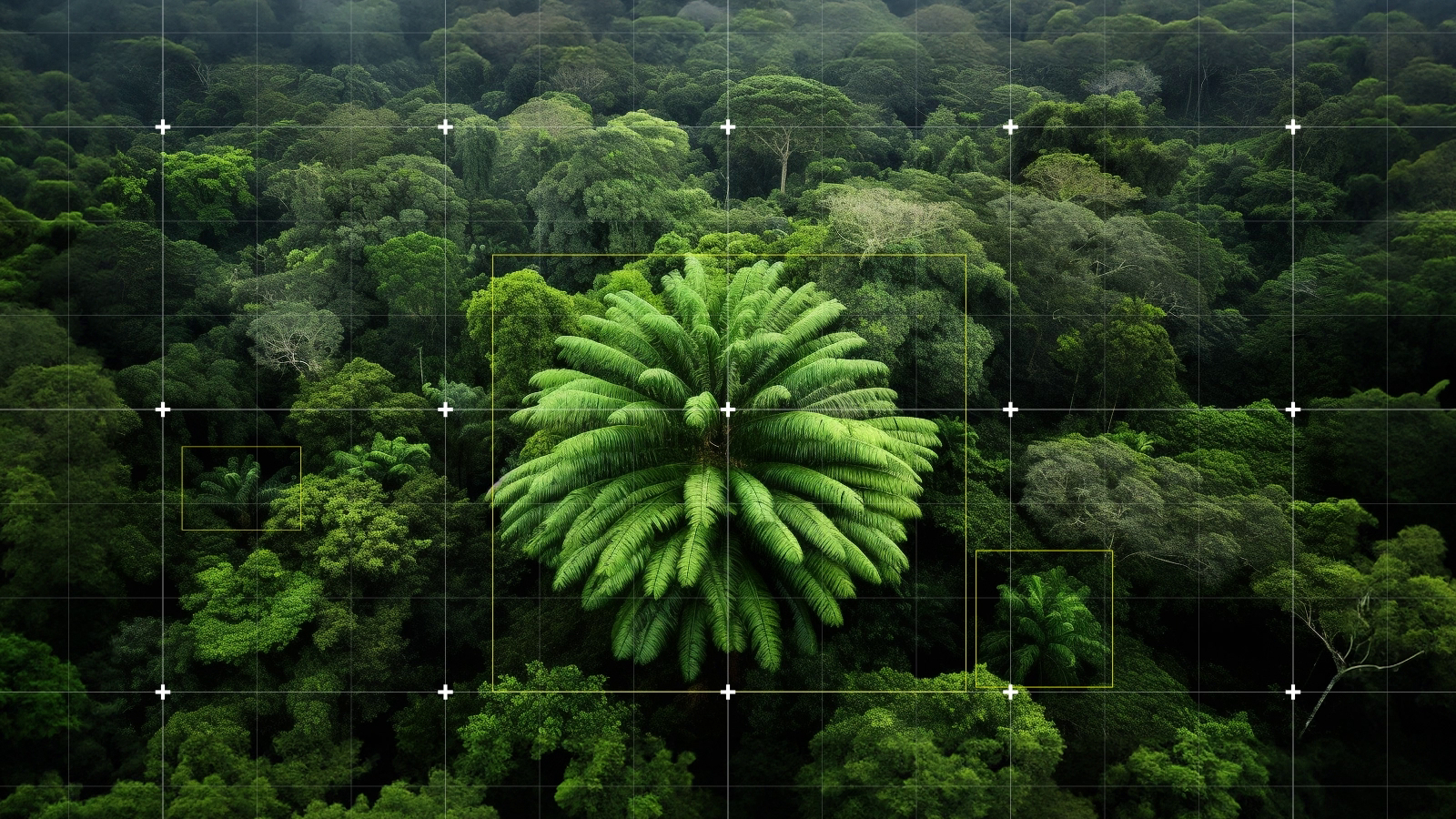

The scientists then use AI algorithms to sift through the visual imagery collected by the drone. "Our project's approach to using AI focuses on the visual identification of cycads, which resemble palm trees when viewed from above," said Laura Cinti, co-founder of C-LAB, an art and science collective, and a research fellow at the University of Southampton in England. "Initially, we adopted detection models that are routinely used in the palm oil industry for counting palm trees, but to optimize it for our specific viewpoint and unique shape of cycads, we trained our own image recognition algorithms," Cinti told Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

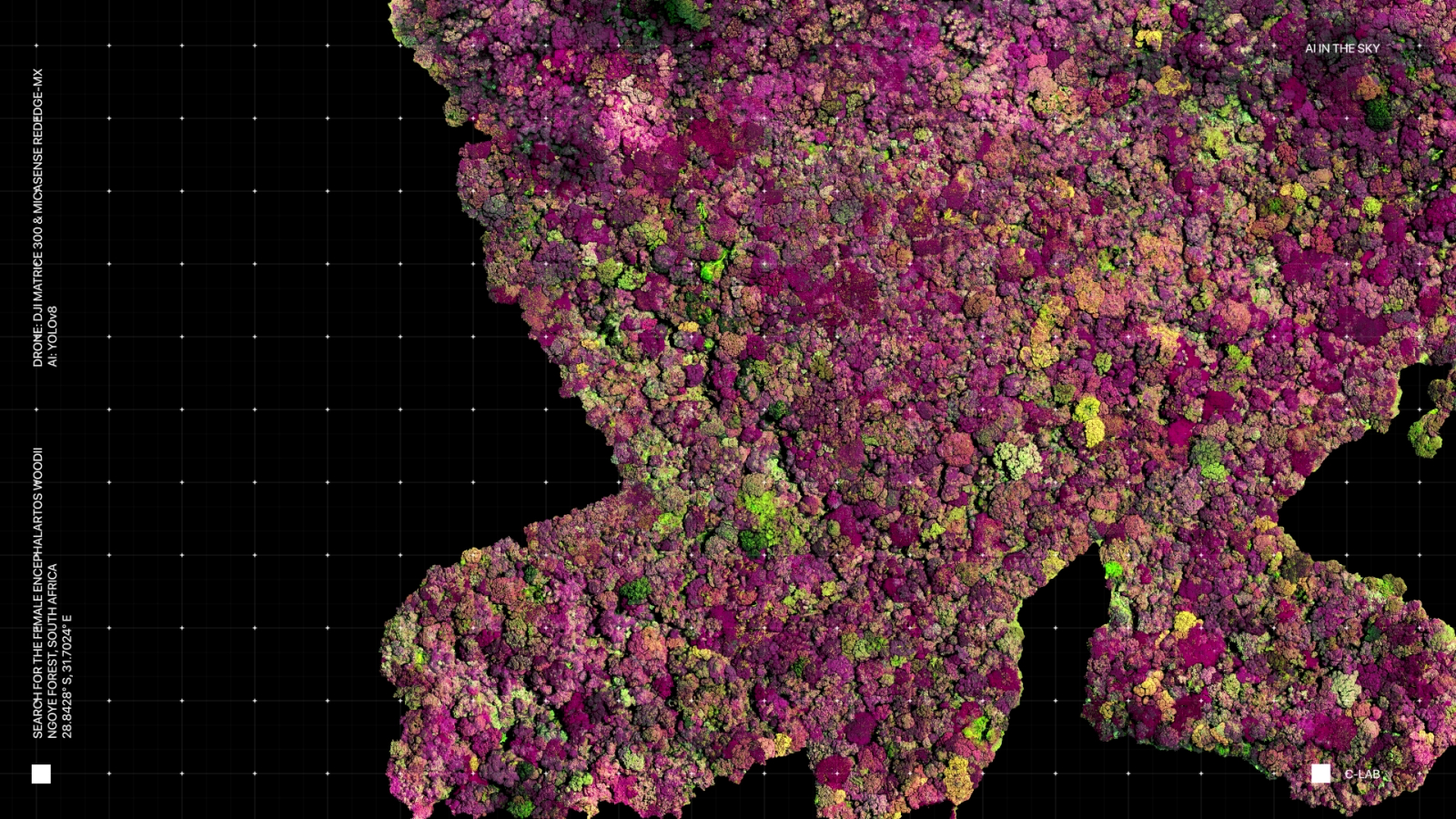

Surveys in 2022 and 2024 captured thousands of images from 195 acres (79 hectares) of the 10,000-acre (4,000 hectares) Ngoye Forest. The drone cameras captured images in five wavelengths in the hopes of identifying the cycads' unique spectral signature, making it easier to distinguish them from the surrounding trees. "We analyzed ecological features to strategically target areas where cycads are most likely to be found, starting at the forest edges — where E. woodii was discovered," Cinti said. Previous surveys conducted by other scientists have been fruitless.

The researchers ran the thousands of images through YOLOv8, a computer vision model used in image-recognition tasks, Cinti said. "A separate generative AI system created synthetic maps with cycads in various environments to improve the model's ability to recognise cycads in diverse contexts," she noted. They trained the model using a range of photographs of various cycad species and placed them in digitally generated canopies to teach the program what their target might look like from above.

Hilly terrain and cloud cover made analyzing the images extra tricky. The team plans to continue refining the model.

Promising candidates can then be inspected by closer passes of the drone. "We can guide some of these drones using first-person perspective, which enables us to do fine navigation and obtain detailed close-ups," Cinti said. "However, as a final step, ground truth verification is always necessary to confirm the findings."

If a female is located, it would likely be removed from the wild. Ideally, it would produce cones. "In controlled environments, pollination can be managed either naturally or artificially. Once seeds are produced, they would be carefully cultivated to ensure healthy growth," she said. The ultimate goal is to produce fertile, healthy seedlings that could then be reintroduced into their native habitat.

Editor's Note: This story was updated on Friday, July 26 at 12:00 p.m. E.D.T. to replace the primary image. An earlier version of this article included an image of the wrong tree species.

Richard Pallardy is a freelance science writer based in Chicago. He has written for such publications as National Geographic, Science Magazine, New Scientist, and Discover Magazine.